The personification of the enlightened age, the first and the only woman in Russia who was President of the Russian Academy of Sciences, a memoir writer, and a close friend of Catherine II. All of these facts are about her — Princess Yekaterina Romanovna Dashkova. This influential woman plotted a vector for the development of Russian science and, together with the first academicians, brought it to the world level. A lot has been said about Dashkova, but historians have been learning more and more details from the life of Yekaterina Romanovna...

Yekaterina Romanovna is a representative of an ancient noble family — the Vorontsov family. As a child, after the quick death of her mother, Yekaterina lived in the family of her uncle Mikhail Illarionovich Vorontsov who soon became the Chancellor of the Russian Empire. Right here, in the country estate, young Katya was absorbed in reading books from her uncle’s large library, meeting the representatives of the Russian society’s elite who were visiting Vorontsov, including the wife of the heir to the throne — future Catherine II. Years later, Yekaterina Dashkova with her husband, the Orlov brothers, and Izmailovsky Life Guards Regiment officers took part in the overthrow of Peter III that placed his wife Catherine II on the throne.

Coup D’état Accomplice

J. B. von Lampi the Elder. Portrait of Catherine II. 1780s. Museum of Fine Arts, Vienna. Source: Wikipedia / Museum of Fine Arts

After her marriage to Prince Mikhail Dashkov, Yekaterina first went to Moscow, and then to the capital city — Saint Petersburg. Here the Dashkovs were introduced to Emperor Peter III. The friendship between the two Catherines resumed. Therefore, during the coup d’état of 1762, Dashkova was among those who supported the future empress. As a reward, Yekaterina Romanovna received 24 thousand rubles, the Order of St. Catherine, and the title of a lady-in-waiting. Some people believe that Dashkova also got lands that, however, turned out to be poor and did not have any special value. However, Dashkova’s organizational skills and own funds helped her revive the unfavorable areas, which upset Catherine II, and their relationship began to deteriorate.

A possible reason was the empress’s belief that her friend exaggerated her role in the coup d’état. Thus, Catherine II wrote that Dashkova had interacted only with lower-level officers and had had no real information on the conspirators’ plans. Dashkova, in turn, recalled in her Memoirs that it was thanks to her that aristocrats and chief dignitaries had come down to the side of Catherine.

Meanwhile, one should not consider the Memoirs a reliable source. Catherine’s era researcher O. I. Eliseeva states that Dashkova’s records need the most thorough verification. For example, the scientist mentions an example of the recollection regarding the two Catherines’ meeting on the eve of the coup d’état. It depicts the future empress as a passive participant, while Dashkova ascribes the decision on further actions to herself. The empress never mentioned such a meeting. Besides, overall, as O. I. Eliseeva says, Dashkova’s Memoirs show a mere author’s vision rather than real events. Therefore, this source is largely literary, not historical.

Head of Two Academies

In 1775, Yekaterina Dashkova went to Europe for seven years. Her son was studying at the University of Edinburgh at that time. The princess traveled meeting prominent people of that era: physicist Joseph Blake, economist Adam Smith, historians William Robertson and Adam Ferguson, etc.

Dashkova used to describe her acquaintances and interesting events in her letters to Catherine II. Their meeting took place in 1782 in Saint Petersburg. Despite their previous disagreements, the meeting of the two Catherines went well. Thus, next year, Yekaterina Dashkova was appointed Director of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. The academic community welcomed this decision, and Ye. R. Dashkova continued the work of M. V. Lomonosov — creation of advanced domestic science. The team of the Academy of Sciences became an influential social force.

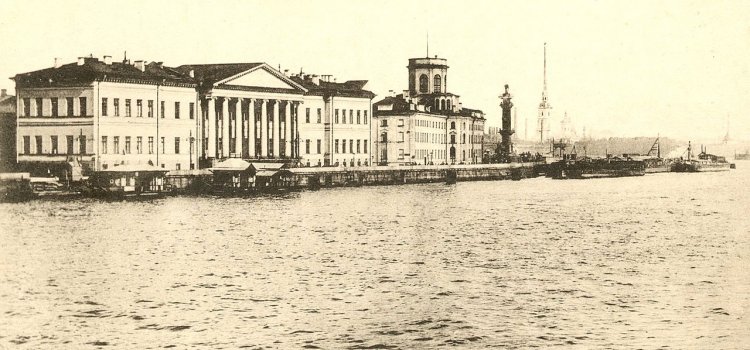

Dashkova put the library and the printing office in order. The number of academicians significantly increased when she was director. Translations of the best works of foreign literature appeared, public lectures by academicians were launched, and the Academy received the main building designed by famous architect Giacomo Quarenghi.

Building of Russian Academy of Sciences (Saint Petersburg). Photo: A. Pavlovich. Source: Wikipedia

But why is Yekaterina Dashkova considered director of two academies? In 1783, the princess offered to the empress the idea of creating a Russian academy to have the Russian language and Russian literature studied in order to glorify the opulence and breadth of the Russian language, enrich and purify it. Almost immediately, the second academy directed by Dashkova started to publish the Academic Dictionary. Such eminent writers of the 18th century as G. R. Derzhavin, D. I. Fonvizin, I. A. Krylov, V. R. Boltin, I. I. Lepekhin, and Professor of Moscow University, M. V. Lomonosov’s student A. A. Barsov were engaged in this work.

The Dictionary of the Russian Academy may be rightly considered a large-scale scientific work of the Enlightenment era. A. S. Pushkin wrote: “The complete dictionary published by the Academy is one of the phenomena used by Russia to surprise attentive outlanders: some extraordinary speed is our undoubtedly happy fate in all respects: we mature in decades not in centuries” (Pushkin A. S. Complete Collection of Works, Moscow, 1949, vol. 12, p. 41).

The work of Dashkova as the Head of the Academy of Sciences was highly appreciated not only by domestic, but also by foreign contemporaries. She was elected a member of the Academies of Stockholm, Dublin, and Erlangen, the Berlin Society of Friends of Natural Science, and the Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. It is no coincidence that A. I. Herzen said the following about Dashkova: “I feel that Dashkova has <...> something strong, versatile, active, something she borrowed from Peter the Great, Lomonosov...” (Herzen A. I. Princess Yekaterina Romanovna Dashkova. The Memoirs. 1743–1810. P. 210).

Collector

During her trip to Europe, Dashkova met many prominent people, including Voltaire, Denis Diderot, Étienne Maurice Falconet, and King Frederick William II of Prussia, who influenced her decision to collect art objects. The princess was acquiring minerals, engravings, paintings for her own collection. By the early 19th century, the collection owned by Dashkova and her brother A. R. Vorontsov comprised about 300 objects.

By the end of her life, Yekaterina Dashkova donated an entire “room of natural history and other rarities” to Moscow University. In 30 years, the collection had been filled with 15 thousand items, including minerals, taxidermied animals, fossils, dried flowers, fruits, and casts. Being an outstanding person of the 18th century, Yekaterina Romanovna not only contributed to the development of the Enlightenment, but also continued the tradition of women’s collecting in Russia.

Yekaterina Dashkova was indubitably an influential woman of her epoch. However, her contemporaries give ambiguous assessments of her personal qualities. The empress, for example, often called her friend a “battle-axe with the manners of a princess,” while A. S. Pushkin wrote the following about Dashkova in his novel Eugene Onegin:

God grant I meet not at a ball

Or at a promenade mayhap,

A schoolmaster in yellow shawl

Or a professor in tulle cap.

Of course, Pushkin is ironic, but at the same time, in the first chapter, he pays tribute to Dashkova and the Academy members for studying the Russian language and literature:

And also that my feeble verse —

Pardon I ask for such a sin —

With words of foreign origin

Too much I’m given to intersperse,

Though to the Academy I come

And oft its Dictionary thumb.

Young Irishwoman Katherine Wilmot visiting the princess in the early 19th century noted: “Such are her peculiarities and inextricable varieties that the result would only appear like a Wisp of Human Contradictions… And woe betide individuality the moment one begins to generalize. But she has as many Climates to her mind, as many Splinters of insulation, as many Oceans of agitated uncertainty, as many Etnas of destructive fire and as many Wild Wastes of blighted Cultivation as exists in any quarter of the Globe!”

Today, it is difficult for us to say what Yekaterina Dashkova really was. Thus, we can learn about the facets of her personality only from the subjective assessments of her contemporaries and historical studies. However, we have the real evidence of the princess’ deeds at our disposal — the deeds worthy of a single woman — the head of two academies.

Photo one the page and the main page: Levitsky. Portrait of Ye. R. Dashkova. 1784. Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens, Washington. Source: Wikipedia / Hillwood

Sources:

I. L. Galinskaya. Princess Yekaterina Dashkova // Herald of Culturology. 2004. No.4.

M. M. Neelov. Princess Dashkova — Outstanding Russian Woman // Omsk Scientific Bulletin. 1998. No.3.

I. V. Krykova, V. S. Semina. Great Enlighteners in Russian Cultural Space in the 18th Century (Catherine II and Yekaterina Dashkova) // Analitika Kulturologii. 2007. No.8.

E. V. Rubtsova. Public, Educational and Publicist Activities of Yekaterina Dashkova in Russia of the 18th Century // Karelian Scientific Journal. 2020. No.1 (30).

N. V. Zababurova. Pushkin and “Professor in Tulle Cap”: On the 270th Anniversary of Princess Yekaterina Romanovna Dashkova // Scientific Thought of Caucasus. 2013. No.3 (75).

S. A. Zelenova, V. V. Kashirina. Ye. R. Dashkova as a Collector of the Enlightenment Age // Universum: Philology and Art History. 2022. No.1 (91).

O. I. Eliseeva. Memory Games. Reliability Problem in the Memoirs by Ye. R. Dashkova // Istoricheskoe Obozrenie. 2013. No.14.