In 2024, the Russian Academy of Sciences, together with the whole country, will celebrate its 300th anniversary. The RAS history and scientific journey are inextricably linked with expeditionary activities. The first academic expeditions allowed researchers to describe for the first time a number of regions, collect the richest material about the flora and fauna, culture and history of various peoples. These collections enriched the country’s museums and gave rise to the development of regional research areas.

The immense variety of academic expeditions includes those that are hardly known to the mainstream audience, but it is their findings that sometimes become the most significant sources of information for the entire global community of historians, archaeologists and art historians. Such were the expeditions to East Turkestan and Mongolia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This period in the history of Russian science is deeply intertwined with the research and administrative activities of Academician Sergei Oldenburg, the head of the Russian Turkestan expeditions, who was never able to publish the findings of his work. This has been done in our days by a team of historians led by Academician Mikhail Bukharin. Below is an interview with Mikhail Bukharin about the significance of the Turkestan expeditions for historical and archaeological science, as well as the life journey of Academician Oldenburg.

— Thinking of the significance of search expeditions for the history of Russia, what is their role in the development of the nation?

— A research expedition is a form of scientific activity that can be found in a number of scientific disciplines. Expeditions are carried out to explore the matters in history, geology, Earth physics, ocean explorations, etc.

As a historian, I can comment on historical research expeditions. Thinking of the first expeditions, we can see that all of them were organized as multidiscipline explorations, and history-related aspects were considered as one of their integral parts.

The multidiscipline nature of these expeditions was manifested in the fact that such government-funded research endeavors were engaged in almost all kinds of research on flora, fauna, archeology and ethnography. The decree on the first Russian research expedition headed by Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt says that he should deal with anything at all “that is remarkable and noteworthy”. That is, he was to record, comment on and forward a report to St. Petersburg about everything that caught his eye. Expeditionary explorations were, are and will remain the basic form of scientific research. Especially for archaeologists.

— Let’s dwell upon the explorations of East Turkestan and Mongolia. What was the key motivation of the government and the Academy behind the exploration of these territories?

— That’s a tricky question. Your wording suggests as if the interests of the government and the scientific community coincided in this respect. However, when referring to archival documents (and we have already collected and published five volumes), you can see that the government had no direct interest in archaeological and art history research in these areas. The scientific community struggled to ensure meager funding for the organization of expeditions. Domestic researchers looked with envy at the activities of foreign colleagues, primarily German expeditions, the funding of which was much more generous, and the interest in expeditions was higher from both the government and all kinds of private entities.

Sergei Oldenburg

It is hard to imagine whether it could have been possible to send any expedition to Mongolia and East Turkestan, if it had been arranged by someone else rather than Sergei Oldenburg, the permanent secretary of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, who personally headed two expeditions to East Turkestan, and acted as a mediator and the main negotiator between the scientific community and the government.

Speaking of the first Russian expedition, the 1898 Mongolian-Turkestan expedition, it was headed by Dmitry Clemenz, a friend and colleague of S. Oldenburg. According to handwritten reports by D. Clemenz, we can conclude that the main interests of the expedition members were about the geological exploration of Mongolia and the search for mineral deposits. It was not stated directly, and D. Clemenz was not a professional geologist. However, 90% of his handwritten diary is filled with details about the types of the soil and the rocks that the expedition members saw. One might get an assumption, sometimes growing into confidence, that the nature of this expedition was not multidiscipline, and archeology was rather a supplementary area of interest in this case. I believe the expedition’s mission was to search for minerals to be mined and used for the needs of the country.

Basically, if we recall the first academic expeditions of the 18th century, we can see that in those years the government quite clearly formulated its interests. They primarily focused on mining and the exploitation of territories. Naturally, there was some scientific interest, and researchers enjoyed absolute freedom to record and describe flora, fauna, peoples, study languages, etc. Nevertheless, the government interest was stated absolutely clearly in the contracts for the dispatch of such expeditions.

In later expeditions, which were organized in the era of budget deficits at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, such information was absent. If the government had any interest, again not directly expressed, then it was rather in the sphere of geopolitics. This was influenced by rivalry, including in the scientific sphere, with the UK and other nations, primarily Germany, for control over various centers of culture, the most prominent monuments of ancient art in East Turkestan or, as they also say, Chinese Turkestan.

— The materials you published include letters from researchers such as Sergei Oldenburg, whom you mentioned. Archaeological research of East Turkestan is inextricably linked with Academician Oldenburg. What kind of a person was he? What was his contribution to the exploration of the said territories?

— In my opinion, a whole lecture course can be devoted to the life of Sergei Oldenburg. He was part of the Russian intelligentsia, both pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary. Several decades of the country’s history in their very multifariousness reflected in his life as if in a prism.

Sergei Oldenburg was a scientist and public official. He served as a member of the State Council, Minister of Public Education, and – in 1917 – a member of the Provisional Government. And, most importantly, he devoted his entire life to serving Russian science, ensuring its interests in the most difficult situations, in dire straits. Tough situations were much common in his life than favorable circumstances.

Sergei Oldenburg received an excellent education. He was very lucky to have wonderful teachers and patrons. First of all, this is Academician Viktor Rosen, who favored him and provided backing in the administrative and scientific community. Baron Rosen knew whom to patronize. Many brilliant, outstanding scientists were among his students. The generation of those who were born in the 1860s was absolutely unique. Many of them soon became high-profile achievers. While leaving out other scientific disciplines, I can say that history, archeology, and oriental studies at that time were enriched by truly outstanding scientists, whose contribution is still felt as paramount. And Sergei Oldenburg was one of them.

We can’t say he was the most outstanding figure, if only because he had to sacrifice his own scientific career to administrative service. For a quarter of a century, he held the position of the permanent secretary of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, which in 1917 became the Russian Academy of Sciences, and then the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Sergei Oldenburg repeatedly tried to leave this position, because it consumed up all his time, leaving no opportunities for scientific activity.

That said, Sergei Oldenburg wrote more than 500 scientific papers in his life, but mostly those were small notes, reviews, articles in popular magazines. He had to abandon the science to which he aspired, i.e. a scrupulous study of literature, texts, his work with the yet-to-be-deciphered manuscripts brought from East Turkestan. As the permanent secretary of the Academy of Sciences, he conducted virtually all paperwork. Of course, the Academy of Sciences had a president. However, at that time, the president was a largely representative figure, and it was the permanent secretary who was in charge of all the "routine".

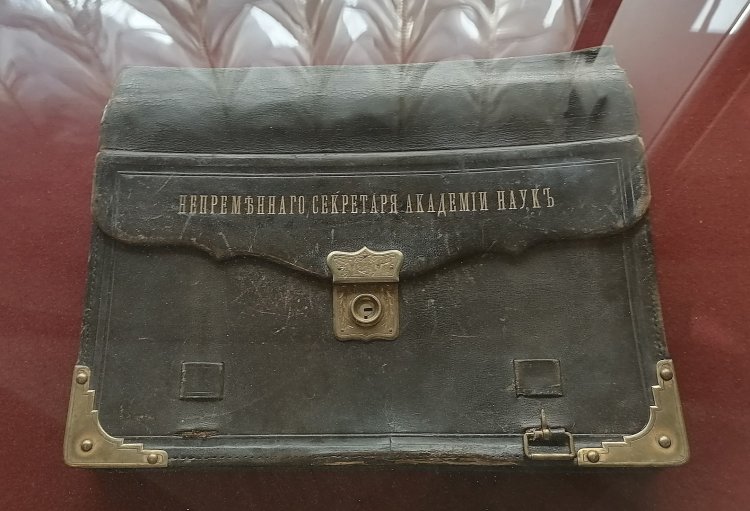

Bag of the Permanent Secretary of the Academy of Scienes. Belonged to S. F. Oldenburg. State Hermitage

In fact, that routine was overwhelming. That’s why Oldenburg’s attempts to take part in the Turkestan expeditions repeatedly failed. He first managed to gather a small team under his command and conduct an exploration expedition only in 1909. These expeditions were funded by the Russian Committee for the historical, archaeological and linguistic study of Central and East Asia, which was part of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Oldenburg represented the Russian Academy of Sciences in the activities of this expeditionary team and could recruit his assistants at his own discretion. There were no academicians among them.

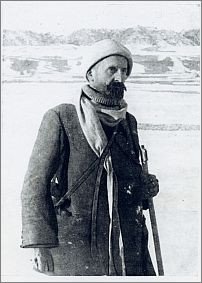

Sergei Oldenburg at the Turkestan expedition (1909)

The history of this expedition is full of undisguised drama (during the first expedition, his mother passed away, during the second, his brother Fyodor deceased). Just think of it: a prominent public official, the permanent secretary of the Academy of Sciences finds himself in very remote, climatically difficult regions, accompanied by a local guide in the endless expanse of steppes and mountains. At some point, a revolver was stolen from him and he was left without a weapon, which was necessary for protection. The safe box of the expedition - a simple wooden box - was repeatedly attacked. Sergei Oldenburg conducted two expeditions in such harsh, uncomfortable conditions. The findings were exceptional, but the cost was huge as well.

The last years of Oldenburg’s life were overshadowed by a rather severe depression. He was spared direct repression, although he appeared on the repressive lists in the late 1920s. However, someone’s caring hand struck him off the final list. However, instead of rewarding Sergei Oldenburg, or at least expressing gratitude and saying simple thank-you for 25 years of continuous research and scientific-administrative feat, he was simply thrown out of this post by a telegram from Sergei Kirov. This is when his activities as the permanent secretary ended. Oldenburg had a farewell anniversary ceremony in 1933, but the transcript of this event makes a pitiful impression both in terms of the membership and the tone of the speeches. This farewell ceremony was not something Sergei Oldenburg really deserved. His close friend Vernadsky, another outstanding scientist and polymath, was by his side in the last years of his life. Sergei Oldenburg died in his apartment in 1934, literally in the arms of Vladimir Vernadsky. Academician Vernadsky repeatedly noted in his diaries how hard it was emotionally for Sergei Oldenburg in the last years of his life. He felt dashed and degraded.

The new Soviet reality, the pressure of the new generation, which no longer lived by science, but considered history as an opportunity to make a political career, put a lot of pressure on Sergei Oldenburg. And, of course, the realization of the fact that he failed to have the main work of his scientific life – the study of the monuments of Buddhist art and architecture – printed, fell on him as a heavy burden. Qianfodong/Mogao, or the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, was the highlight among these monuments. Actually, it was this monument that was the key subject of study during the second Russian Turkestan expedition, which worked on it in 1914–1915.

Strictly speaking, this monument is not located in East or Chinese Turkestan. It is located further east, in the province of Gansu. However, the expedition had already been code-named "East Turkestan", therefore researchers conditionally call this territory East Turkestan.

Sergei Oldenburg’s expedition managed to do more than any other team that worked on this monument. And yet, having spent considerable efforts working at the monument itself, preparing for publication, finding money to publish "The Description of the Caves of Chang-fo-tung near Dun-huang", Oldenburg had to uphold the desire to publish this work primarily in the Soviet Union, rather than in foreign publications. However, the government had no substantive interest in this work. As early as the mid-1920s, desperate Oldenburg agreed to have the book accepted by foreign publishers. Yet this option also failed. Therefore, Sergei Oldenburg never saw the work of his whole life published. And this is one of his personal tragedies as a scientist and administrator.

When we think of the personality of Sergei Oldenburg, we, of course, associate it with a certain brilliance of pre-revolutionary science, outstanding achievements. Yet we must also remember the dire situation the Academy found itself in after the 1917 revolution, the painful intermediary activities between the old staff of the Academy and the new authorities that Sergei Oldenburg had to carry out. He faced so many attacks and accusations – usually unfounded – of collaboration with the new authorities, so many mordant and malicious jokes! At some point, he just waved his hand and stopped making excuses.

In the late 1920s, following a series of structural reforms, the Academy was finally Sovietized, the old staff of academicians was diluted with several dozen new members. Oldenburg’s era in the Academy of Sciences naturally ended. Yet his contribution to the fact that the Academy of Sciences as such remained afloat, science continued to develop in the country in the 1920s, and the dialogue between the scientific community and the authorities had been established, was truly significant.

— Let me make sure I’ve got this right: it wasn’t until recently that his works have been published?

— That’s true, indeed. After the death of Sergei Oldenburg in 1934, his colleague, Indologist Academician Fyodor Shcherbatskoy, a number of other colleagues, and his widow Elena Oldenburg teamed up to type out the handwritten draft prepared by Sergei Oldenburg and figure out the abbreviations. Unfortunately, this work was never finalized. They prepared three typewritten copies. Fyodor Shcherbatskoy was already a very elderly man, and in the course of this work, he suffered a stroke. His handwriting on the typescript can be seen, but he did not work with the manuscript. Elena Oldenburg and Olga Kraush, the typist, worked with the manuscript, but they failed to figure out the nomenclature and abbreviations.

Nevertheless, we had at our disposal three typewritten copies of Sergei Oldenburg work and his handwritten draft. One copy is kept in the St. Petersburg branch of the Archives of the Russian Academy of Sciences; the second is in the Oriental Department of the State Hermitage, and the third is in the Institute of Oriental Studies, now the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

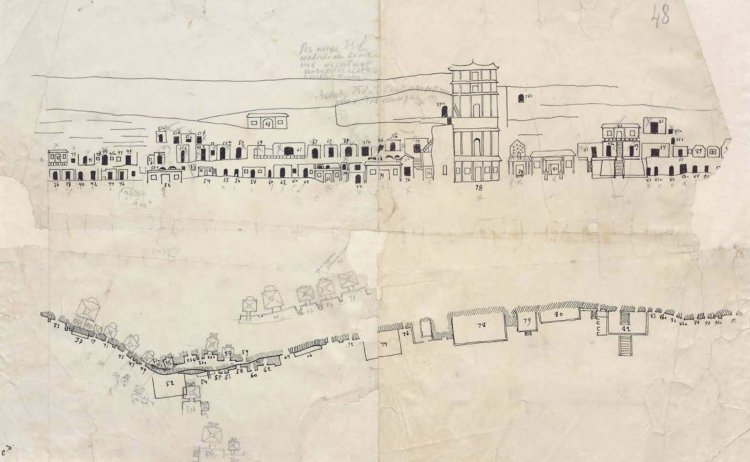

Smirnov N. The Mogao Caves, also known as the Thousand Buddha Grottoes or Caves of the Thousand Buddhas

We proceeded another way: we began to painstakingly read the handwritten drafts. I have long been accustomed to Sergei Oldenburg’s handwriting, it is not the most readable one, but not the most difficult either. I used to deal with much more difficult handwritings of some academicians whose scientific heritage I happened to work with.

Sergei Oldenburg wrote his drafts right in the field. Sometimes traces of a rough rock on which the paper lay are still visible. Sometimes he clearly faced the shortage of paper and then indulged in all sorts of tricks. On a square-ruled sheet, he first wrote on odd lines, then on even lines, and then wrote along the perimeter. And we had to find some logic in all these fuzzy patterns. Of course, this indistinct writing manner baffled readers. To crown it all, most of the text is written in abbreviations. However, we have managed to figure them out.

When we completely read through Sergei Oldenburg’s handwritten text – and these are several hundred sheets – I began to compare it with typescript. It turned out that if modern explorers take the typescript and go to the caves explored by Sergei Oldenburg (and there are more than 450 of them), then they will get lost in those caves, since the nomenclature details were misinterpreted. We had to put the typescript aside and get along without it.

Now and again, I had to consult the typescript, of course, where the handwritten text was especially difficult to read. If the two interpretations matched, it gave me a certain confidence that it was read correctly. However, reading is just one side of the issue. It was necessary to comment on all this and build it into the general context of the history of the monument.

In addition, we found previously unpublished works among the papers of Sergei Oldenburg, which constituted the fund of his Qianfodong caves study heritage. We also published these papers in our five-volume edition. It was especially hard to deal with these papers.

They were written with a pencil, not a pen and ink. A text handwritten with a pencil fades over time and it is difficult to read pencil drafts made more than 100 years ago. Moreover, the initial notes, some sketches that he made for himself, he also wrote mostly with abbreviations: two or three letters instead of a normal word. Imagine what it’s like to read multi-page texts written in such a "Morse code". Finally, we managed to cope with it. Now we can say with confidence that the work of the second Russian Turkestan expedition headed by Academician Sergei Oldenburg has been almost finalized.

And it’s not just some antique artefact. All this is absolutely relevant and necessary for researchers who are now working with these monuments, since Sergei Oldenburg managed to accurately describe the frescoes and sculptures themselves, and also describe all the colors that were partially lost later on. In addition, some monuments were deliberately damaged or improperly restored.

Despite the fact that Sergei Oldenburg’s archival materials, including the Cave of the Thousand Buddhas research, were translated into Chinese in the 1980s, now the Chinese Research Academy of Dunhuang is preparing a contract for the translation and complete publication of all five volumes that we have prepared. There’s a good reason why colleagues from Germany, France and other countries refer to these works in their reviews. This is not just some museum artefact, but also the material demanded by the current generation of researchers studying the original state of the most important monument, which is on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The relevance of Sergei Oldenburg’s work did not decrease. Moreover, it has grown over the years due to the destruction of the monument itself.

Birkenberg V. Dunhuang is a county-level city in Northwestern Gansu Province, Western China

— Has it uncovered new facets of Buddhist art that we did not know about?

— Quantitatively, the number of the described monuments is just amazing. Oldenburg’s views on the chronology of Buddhist art, on how the Indian and Chinese schools interacted, on how folk art meddled in Buddhist art with its storylines are well known from his other – more concise, but also later and much less detailed – works. The Description of the Caves of Chang-fo-tung by Oldenburg was compiled "in hot pursuit" as very little time passed from the moment the caves of Qianfodong had been discovered to the start of work by Sergei Oldenburg. That’s why it is so valuable for the history of art. He was one of the first researchers of this site, and his research significantly outperforms the work done by his contemporaries, colleagues from the UK and France, in terms of quality and thoroughness. Modern researchers – in particular, colleagues in Berlin and Leipzig – have been shocked in a good way by our publication of Sergei Oldenburg’s papers and its scale. Despite the rather involuntary severance of scientific ties with foreign scientists, I continue to maintain close scientific and personal contacts, including with German colleagues working in this area. We constantly receive requests for comment on what Sergei Oldenburg wrote on this or that matter. Basically, the demand for these materials is higher overseas than in Russia.

— What’s the reason?

— Buddhist art remains a fairly specific area for a broad academic and research community. Naturally, the frescoes of St. Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod arouse much more interest; after all, this is an important element of Russian culture, the history of Russia. Normally, an average Russian person of today knows extremely little about where Chinese Turkestan is. Therefore, these expeditions and these papers are rather narrowly focused activities from the point of view of the modern researchers. But it’s a natural way science develops: a broad area is constantly being split up, with new and narrower thematic blocks gradually surfacing. And, of course, these stories were not any mainstream archeology line even back in the early 20th century. This is evidenced, among other things, by the fact that the expeditions were tiny in terms of their membership.

In his first expedition, Sergei Oldenburg was eventually left alone. In the second expedition, the artist Boris Romberg assisted him. In fact, there was neither active interest on the part of the government, nor money.

We can compare it, for example, with simultaneous expeditions to Mongolia headed by Pyotr Kozlov, a military geographer, ethnographer, and archaeologist, which culminated in the discovery of Khara-Khoto and monuments of Tangut literature. These expeditions were much better staffed. I cannot say that Kozlov’s expeditions were better funded, but Sergei Oldenburg had to work in some absolutely extreme climatic and financial conditions, even in comparison with the expeditions of his colleagues. He and his colleagues in East Turkestan had to defend the possibility of working on certain monuments in opposition to foreign counterparts, despite the fact that the mentioned Russian Committee was the international coordinating body for a number of expeditions operating in this region. However, every time the German expeditions got the best monuments, because they were the first to get there, in circumvention of all the agreements. Also, there were situations when German expeditions tried to oust Russian expeditions from the monuments that they had managed to take up. Once there was the threat of the use of firearms. In fact, some placability and naive idealism were part of Sergei Oldenburg’s personality. He even tried to unite several foreign expeditions into a kind of Holy Union and called on everyone to jointly explore ancient monuments for the benefit of humankind. At first, the German counterparts agreed, but in the end, they took out everything that they could, and broke down and abandoned everything that they could not. This is how the idealistic cooperation that Sergei Oldenburg called for ended. It is clear that Oldenburg could not publish his tirades against foreign colleagues who mutilated a number of monuments with their desire to fill their own museum collections rather than to enrich human culture. But when we turn to his diaries and notes he made on the go, we can see that sometimes he was simply furious at what he had to see. That is, among other things, in those years there were two conflicting ideological approaches - not so much research, but rather ethical ones.

— Is there any evidence of how Russian researchers and diplomats were received in these territories? After all, another way of thinking, a foreign language and culture. Was there any resistance?

— There is a lot of evidence for that. The attitudes varied a great deal. This largely depended on how local diplomatic missions worked. The Russian side was quite lucky, as Nikolai Petrovsky had been the consul (since 1882) and consul general (since 1886) in East Turkestan. He was an outstanding figure with a very challenging trajectory of life. He was fond of all sorts of revolutionary ideas and was eventually sent into exile. While in exile, he educated himself. He did not speak oriental languages, but deeply fell in love with the culture of those peoples on whose land he happened to live, and was imbued with sincere respect for it. Nikolai Petrovsky was engaged in collecting, one might say, amateurish collecting. And gradually his collection of antiquities began to be of some value. In the early 1880s, he donated the collection to the Oriental Department of the Russian Geographical Society. The recipient of these parcels was the aforementioned Baron Viktor Rosen. Gradually, Sergei Oldenburg also joined this activity.

Nikolai Petrovsky was a very tough person in defending the interests of the Russian state. On the other hand, he was well aware that only flexibility and sincere respect in relations with the local population and the Chinese authorities could promote Russian interests in Central Asia and the Far East, including scientific interests.

Therefore, the locals treated Sergei Oldenburg, when he came there later on, also with great respect. The foundation was laid by Consul Petrovsky, whose achievements were continued by his successors in this office.

— Why didn’t the locals protect the monuments that were taken out by the German archaeologists? Were these not sacred places for the people who inhabit these territories?

— No, these are monuments of Buddhist culture. This was an alien culture for the local Muslim peoples. In his notes, Sergei Oldenburg reports that some frescoes had been deliberately spoiled, for example, desecrators gouged out the eyes.

Also, not all locals had the proper understanding and level of cultural development in order to take care of these ancient monuments. For some, they were even a source of profiteering. The conditions, in which the local Uighur population lived, were quite tough, as evidenced by the description of the daily routine and folklore in Oldenburg’s diaries. They are quite remarkable not only from the point of view of history, archeology and Buddhist art, but also as a way to explore the researcher’s personality. He was keenly interested in everything around, wrote down everything in the course of the expedition, made ethnographic and daily-life sketches.

Academician Mikhail Bukharin

— What is the value of the East Turkestan and Mongolia expedition for history and archeology?

— The value of these expeditions for the study of Buddhist art and architecture is not limited to the beginning of the 20th century alone. The scientific contribution of these East Turkestan and Mongolia expeditions is still relevant even today, largely because the monuments have undergone significant destruction. The published materials to some extent allow them to be reconstructed and restored to their original form.

Certainly, some caves have been preserved in good condition, but many are not. The level of care and detailed approach with which Sergei Oldenburg recorded every little item, cannot be compared with how, say, the French expeditions worked. In addition to photographs (about 2,000 yet-to-be-published slides), Sergei Oldenburg created architectural layouts and sketches for each cave. He was not a professional draftsman, but he tried to draft each cave on the layout as detailed as possible. A small team under my leadership managed to reconstruct all this. Irina Tunkina, director of the St. Petersburg branch of the Archives of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and Svetlana Shevelchinskaya were also members of the task force responsible for the publication of "The Description of the Caves of Chang-fo-tung near Dun-huang".

I don’t think these volumes have been properly integrated into the scientific environment yet. The version in Russian is in demand only in Russia and among those foreign colleagues who read Russian, but those are a rare phenomenon.

— What is your current work about?

— I continue to study the history of East Turkestan. However, we had to take a break for now. The reason is simple: the materials I need for further work are in the Hermitage. I don’t work at the Hermitage, and besides, they need restoration. The photo archive of the expedition, containing more than 2,000 photographs, is gradually deteriorating. Negotiations are underway with the Hermitage about this issue, there is mutual interest, but there is no time and funding for this work. Hopefully, we will return to this subject someday and the photo archive will be published.

However, there is a lot of work in other areas as well. I am majoring in the history of the ancient world, the history of the Hellenistic East. I continue to explore the ancient history of the Red Sea basin. Unfortunately, this region is not safe right now. Russian archaeologists are not currently working in Yemen, so the sourcing of new information in this area has slowed down drastically.

Together with my St. Petersburg and Moscow colleagues, I am also actively working with materials on the history of early Soviet and late imperial historical science. There are quite a lot of materials, and all of them are concentrated mainly around the process of how the imperial time science came into contact with the new Soviet reality, how the view of historians on certain processes took shape in the 1920s–1930s, how history was institutionalized, how certain institutions were formed. I must note the significant contribution of two of my St. Petersburg colleagues, Vitaly Ananyev and Olga Sapanzha. Collaborating with them is not only pleasant from the point of view of personal communication, but also highly productive. Over the past three years we have published a few major monographs, the number of our papers on this subject has exceeded one hundred.

We have managed to do many exciting things. We have pulled out of oblivion a whole corpus of archival materials that were in very hard-to-reach places. The importance of these activities goes beyond purely antiquarian interest. The development of science is based on the experience of many generations, which, among other things, allows people to avoid falling into the same trap twice. Meanwhile, in many respects, the lack of substantive attention to the history of science also entails a number of challenges that Russia’s science is facing now. The idea of how science – especially historical science – developed in the 1920s and 1930s has changed. Historical science evolved non-linearly in this period. It cannot be said that the entire Soviet historical science developed in line with the guidelines set by Mikhail Pokrovsky based on a pure ‘class approach’. Such things did happen, no doubt, and the mentioned conditions influenced the conclusions – scientific or pseudoscientific – that certain scientists came to. But the number of modalities along which research proceeded was much greater than we could have imagined five years ago, as was the number of dramatic and sometimes tragic twists that Soviet historical science underwent.

Over the past 20 years, it has become customary to say that the old historical science was rooted out, and a new Soviet one came in its place, which became a servant of political interests. This is not entirely true. This is an approach that absolutizes one of the trends, and there were quite a few of them.

In those years, there were also those who tried to do their job honestly, serving purely scientific interests, trying not to respond to what was happening around. There was, of course, a lot of tragedy both in personal and scientific aspects of life.

Frankly, I am looking forward to getting back to further work on researching documents about expeditions to East Turkestan and Mongolia.

— Hopefully, your expectations can come true as soon as possible.

— I wish they could.