Photo source: Stewart Nimmo / Nimmophoto

Living fossils are animals and plants that have survived virtually unchanged from the ancient times through hundreds of millions of years to the present day. These species are morphologically very similar to their predecessors that lived half a billion years ago and later, so we can get an idea of what the ancient Earth looked like and what its living environment was like. Our planet has dozens of animal species commonly called “living fossils.” Today we will talk about the most outstanding representatives of the relic fauna.

Latimeria: “Grandmother” of Human Beings?

This fish is called an icon of evolution and a close relative of human beings. The reason is that the origin of terrestrial vertebrates, like you and me, is inextricably associated with this bizarre fish. Latimeria belongs to the class Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fishes). They were exactly these marine fauna representatives to give rise to all the tetrapods, or four-limbed vertebrate animals, that first ventured onto dry land and became the ancestors of amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. The first tetrapods appeared on the Earth about 400 million years ago, during the Devonian period often referred to as the Age of Fishes. It is noteworthy that Latimeria itself, being a relative of land dwellers, has remained in the sea with practically no changes over several hundred million years.

Probably, the most surprising thing about Latimeria is its muscular fins resembling the paws of a land animal. Besides, none of the modern fishes has a tail like that of Latimeria. It consists of three blades, the middle one being longer than the other two blades and located in the center. This additional isolated blade is a rudiment of the tail found in ancient fish forms. Latimeria’s large and thick scale also reminds of the distant ancestors of all terrestrial vertebrates.

Today we know two types of Latimeria: Latimeria chalumnae found off the eastern and southern coasts of Africa, and Latimeria menadoensis found in Indonesia. Photo source: jonnysek / 123RF

Indeed, if Latimeria remained deep underwater, then which members of the bony fish class Sarcopterygii were the first ones to reach land and become our closer relatives? Meet Tiktaalik, a popular hero of the Internet memes and probably an intermediate between fishes and land animals (the first amphibians). It is believed that Tiktaalik began to move from water to land about 375 million years ago. Thus, the first primitive amphibians and later, more complex animal forms appeared on the Earth thanks to Tiktaalik that, using its primitive light and fleshy paws, dared to master an unfamiliar territory. Discovered in 2004, Tiktaalik quickly became and is still a hero of memes. Netizens blame this curious fish for taking a global evolutionary step by crawling out onto land millions of years ago, thus leading us to intelligent life, and subsequently – to a need to go to work, study, pay taxes, and face other vicissitudes of our terrestrial existence.

Tiktaalik's first steps. Video source: BBC

Tuatara: Lizard with a Third Eye

An ancient reptile from the order Rhynchocephalia, the tuatara, is as interesting as the mysterious deep-sea latimeria, because it is the only surviving member of its order. Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) are found on the rocky islands of New Zealand where a special conservation regime meant to protect this species has been in place for 100 years. All dogs and cats were removed from the islands, while rodents damaging the Tuatara population were exterminated.

These endemic reptiles dating back to ancient Maori legends are notable for having a third eye. The so-called parietal eye (that lies between the two real eyes) was common to many primitive reptiles of the Paleozoic era, a geological period in the Earth’s history lasting from 541 to 252 million years ago. Tuatara are not the only animals having a third, or parietal, eye ― many modern lizards also possess it. The tuatara itself is not a lizard, but, like lizards, belongs to the class Reptilia. Scientists assume that its third eye, although being light-sensitive, is not responsible for vision, but regulates its biorhythms, contributes to thermoregulation and helps navigate in space. For vision, the tuatara uses its two common eyes.

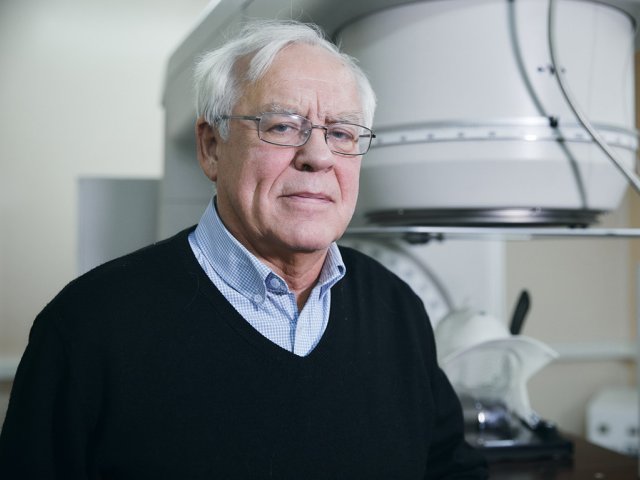

Tuatara. Photo source: Stewart Nimmo

Tuatara are older animals than Latimeria, but like the latter, these reptiles have remained virtually unchanged over their hundred-million-year evolution. The unique reptiles have survived to this day because they had only few competitors and were sufficiently isolated from other fauna representatives able to displace them from the ring of life.

Horseshoe Crabs ― Owners of the Most Expensive Blood in the World

The prehistoric animals called horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) are known worldwide as living fossils. These marine relatives of spiders and scorpions have existed virtually unchanged on our planet for over 400 million years, living off the coast of Southeast Asia and on the east coast of the United States.

Although horseshoe crabs are relict arthropods, people harvest them because of their blue blood. Hemocyanin containing a lot of copper plays the role of hemoglobin that carries oxygen in their blood, which explains its blue color. Extraction of horseshoe crabs’ hemolymph has become a lucrative industry, and one liter of this liquid costs about $15,000. It is mainly used to make medicines that help detect bacteria in various medical solutions. Horseshoe crabs’ hemolymph has been helping humans fight diseases since the 1970s.

“People catch horseshoe crabs, take up to 30% of their hemolymph, and then release them back into the sea. The pharmaceutical industry claims that the mortality rate after such a procedure is several percent, while animal rights activists and environmentalists believe it is about 30 percent. More and more often, scientists voice their concerns about the declining number of horseshoe crabs due to their involuntary ‘donation’, up to their endangered status,” write the authors of the non-profit DonorSearch project.

Thousands of horseshoe crabs are milked like cows every year. Many animal advocates from all over the world stand against such exploitation of the ancient animals. Scientists are developing an analog of blue blood to be used for medical purposes. However, it will obviously take a lot of effort and time to make pharmaceutical companies switch to such a substitute, as it is not that easy to stop the multimillion-dollar business that deals with harvesting and exploiting horseshoe crabs.

Platypus: One of the Few Venomous Mammals

Unlike the three previous heroes of our article, the platypus is no older than the dinosaurs. However, this fact in no way diminishes its uniqueness: this is one of the few venomous mammals on our planet!

Steropodon, 110 million years ago, Cretaceous period. Photo source: Matt Martyniuk (Dinoguy2), own work; Wiki2

Platypus. Photo source: lello4d / 123RF

“Egg-laying mammals (echidnas, long-beaked echidnas, platypus) have hardly changed over millions of years. A platypus-like animal appeared during the Cretaceous period (a geological period that lasted approximately from 145 to 66 million years ago. ― Editor’s note) and looked almost the same as our modern platypus. These animals have hardly changed in the past 110 million years, at least in terms of their appearance, although internally they are different to a degree from the platypus,” said paleontologist Yaroslav Aleksandrovich Popov in his lecture “The Era of Animals” hosted by the Arche Cultural and Educational Center.

The platypus still retains many of the primitive traits it acquired from the earliest mammals, Yaroslav Popov says:

“I mean not only its ability to lay eggs and the absence of sensitive lips, but also its venom glands, which makes the platypus almost the only venomous mammal on the planet. Once almost all animals had such venomous spurs, but today the platypus is nearly the only animal to have them.”

The unique animal platypus is one of the symbols of Australia where it lives. The platypus is depicted on the reverse of the Australian 20-cent coin.

Today we have told you about several living fossils on our planet. Apart from Latimeria, Tuatara, horseshoe crabs, and platypuses, such relict animals also include the chambered nautilus, Lingula brachiopods, possums, various species of sharks, and many other fauna representatives. These animals have survived to this day intact largely because of their specific habitat and felicitous anatomical structure.

Scientifically edited by Anton Vladimirovich Kolesnikov, Candidate of Geological and Mineralogical Sciences, Leading Researcher of the Geological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Photo on the website main page: Leonid Dombrovsky