Food, along with other physiological needs, such as water and air, is at the very foundation of the Maslow's hierarchy of needs. While climate change and today's economic agenda both dictate new requirements to the methods of breeders' work, and to the results they are expected to deliver.

What direction should the development of agriculture and plant breeding follow, how can we reduce the carbon footprint of the agricultural industry, and are plant breeders prepared to face the climate change? These matters are discussed in the interview with Doctor of Sciences in Biology, Director of the Nemchinovka Federal Research Center Sergey Ivanovich Voronov.

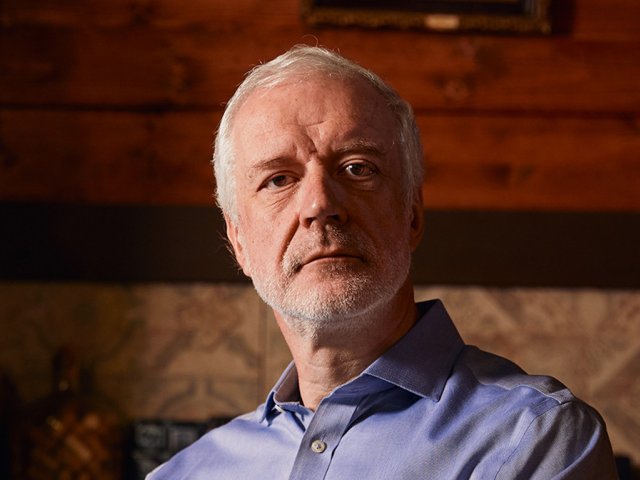

The interview with Director of the Nemchinovka Federal Research Center Sergey Voronov

– This year, the Nemchinovka Federal Research Center is celebrating its 90th anniversary. The Center’s scientific results are universally known: those are new grain varieties that have a consistently high and good-quality yield in the nonchernozem belt of Russia. What varieties are growing in the fields these days?

– Let us start with a few words about the Center itself. For 90 years, the institute has been a place of an immense research process, and perhaps one could even say that it caused a revolution. Its essence is in that in the past, there was nearly no wheat cultivation in the central nonchernozem belt of Russia. Food wheat, the kind that became the staple product for the central Russia, appeared with the creation of our Moskovskaya 39 variety. And that is a high-quality, high-protein and high-gluten grain.

Today, the work of plant breeders aims to improve the quality of grain, achieve the plasticity of varieties and expand the cultivation area for our varieties throughout Russia, from Kaliningrad to Sakhalin. And it is true, our varieties do grow even on Sakhalin. The only difficulty we face is with the delivery of seeds there.

Today's varieties are Moskovskaya 82 and Nemchinovskaya 85 winter wheat varieties. We have created Russia's only interline F1 hybrid of winter rye called Nemchinovsky 1. Our barley varieties enjoy great demand as well, growing in 10 regions of the country. A quarter of all varieties of oats were also created by Nemchinovka breeders. We have an extensive range of varieties that are in demand in many regions due to the high quality of grain and its high yield, they offer a happy combination of winter hardness, short stalk, standing power, early maturity, grain shedding, and pre-harvest sprouting, immunity to profiling diseases, as well as a high baking, cereal and brewing value.

Nemchinovka's varieties were created by a stellar ensemble of scientists who have been conducting breakthrough research for 90 years. They created Triticum-Agropyron hybrids that made it possible to expand the range of winter wheat far to the north. They created amphidiploids that improved the quality of wheat. No other country in the world has grain of comparable quality: our winter wheat varieties have up to 20 percent protein content, and up to 40 percent gluten content.

– Is this a high content compared to the results of other countries?

– Usually, protein content in soft wheat grains is at 11-13 percent, and gluten content is at 22-25 percent. Our wheat varieties contain an average of 14-15 percent of protein and 28-30 percent of gluten.

– You mentioned rye, wheat, and hybrids. Is there a single type of grain that enjoys the highest demand of all?

– Almost all of our grain varieties are in demand. Our winter wheats are among the top three varieties in Russia, along with Krasnodar and Rostov varieties. Of course, our spring soft wheat varieties do not measure up to the spring varieties from Omsk Research Center. But our barley is at the very top. Today, a quarter of all barley varieties are the product of Nemchinovka, and I wouldn't be able to single out any specific variety. They are all in very high demand.

A general problem today is that there is little demand for Russian brewing varieties. Despite their high quality, companies prefer to import their own grain. This is because the majority of brewing companies have foreign origin, and they deliver their own grain. That is an issue of economy and low awareness of similar grain varieties available in Russia.

There is little demand for triticale and, completely undeservedly, there is no demand for rye, not only for our varieties, but for any types across the country. Today, this crop is used to sow just one million, maybe one million and two hundred hectares, while in the past, it used to be the essential bread crop.

Stand demonstrating the achievements of the Nemchinovka Federal Research Center at Skolkovo

– When did rye lose its popularity and what caused that?

– Winter wheat came to the central nonchernozem belt of Russia, and its lands were now used to cultivate local wheat bread. That is driven by popular demand: people are eating more of white bread.

Today, it is understood that there is demand for rye and that it can be a healthy product choice, but it takes time to reshape the system. There is some serious demand for rye coming from Tula and Moscow Regions: last year, we sowed 3,000 hectares, which means that we are witnessing a comeback of this crop. Especially now that there is the first Russian hybrid.

– What are the long-term objectives for the Nemchinovka Institute today?

– We are facing formidable tasks. The first one is to maintain our leadership in competition against foreign varieties. Today, 95 to 98 percent of all winter wheat that is sown in Russia is represented by domestic varieties. These are the varieties that we have bred and that we do not import.

But there are international competitors that are trying to enter this sector, especially transnational companies, such as Bayer. The company has obtained a government permit to carry out plant breeding and promote its own varieties. But that task is not as easy as our colleagues seem to think. Their variety needs to pass a very serious environmental check. Their varieties either fail from frost, or from moisture, or cannot compete with our varieties based on other parameters.

That is why another objective we set for ourselves is to quickly create new, higher-quality varieties that would be adapted to various environmental conditions. These varieties should be less vulnerable to various adverse conditions. First of all, they should be resistant to diseases and pests, which means that they would require fewer chemicals to protect them.

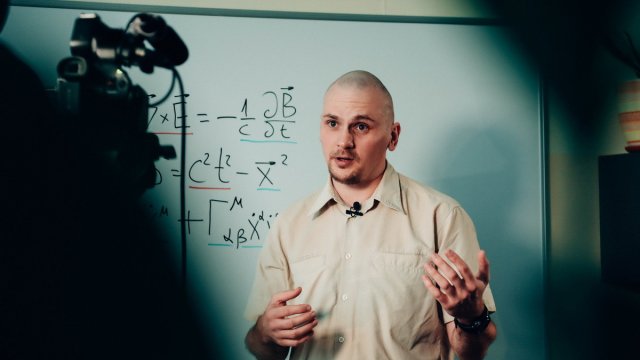

In general, we have everything to deliver fast breeding using modern genetic and biotech methods. On our new territory in Skolkovo, we have the latest fifth-generation equipment for breeding and genetic research and top instruments that make it possible to conduct environmental studies. We can detect up to 80 elements of the Periodic Table with a high level of accuracy.

Director of the Nemchinovka Federal Research Center at Skolkovo Institute

Director of the Nemchinovka Federal Research Center at Skolkovo Institute

– What innovations and new technologies do plant breeders expect to see? Is there anything you are running short of?

– What we run short of today is the material and technical resources. There are not enough sowing machines, combines, field infrastructure, seed cleaning plants and installations. That is a problem for all research institutions in our industry.

This year, with assistance from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, we are making a leasing purchase of machinery for a total of 120 million, and the entire program will grant a total of 350 million. I hope that over 3 years, we will be able to purchase high-quality equipment for breeders.

That is vital for the purity of any variety – no grain admixtures are allowed: it would be a disaster if rye or triticale found their way into our wheat seeds. Our breeders are very particular about this, and we sometimes have heated arguments along the lines of “Why did you contaminate my wheat?” Today, this is a sore spot for breeders: while we were able to improve our laboratory facilities to the highest level, the production part still requires a lot of attention.

Ten years ago, our Institute suffered a disaster: our entire experimental field was seized for the creation of Skolkovo Innovation Center. Our experimental field was moved to a base in the Vnukovo district. But today Moscow is looking to seize that site as well, for the construction of MosExpo. That is an important goal, of course, but I believe it is unwise to ruin a leading plant breeding center for that purpose. The transfer of land was reviewed by a government commission, and they said, “That is not allowed. It can be used for research only.” Today, the working group’s work within the government commission is carried out by the Ministry of Finance, and so far, the authorities have been listening to us. But how long will it last? I wish we could see support from the government, not opposition.

Director of the Nemchinovka Federal Research Center at Skolkovo Institute

– Today, there is an active discussion of low-carbon development. Agriculture is singled out as one of the industries that is most harmful to the environment. What is the reason for this and how can we fix the situation?

– Any contaminations are the result of process violations, when a large number of agricultural chemicals and fertilizers are used at the wrong time. Waste water contaminates rivers and lakes, affecting the quality of groundwater. But that can only occur when processes are not followed.

As for the carbon footprint: the greatest greenhouse effect comes from the evaporation of rivers and oceans. Carbon comes second, followed by methane and nitrous oxide. We understand that we cannot influence the evaporation. The only thing we can influence is the carbon balance.

Speaking about agriculture: it is true that there are increased carbon dioxide emissions, but only from the use of black fallows. When photosynthesis occurs, all plants, especially those with a large leaf surface, absorb this carbon dioxide and deliver carbon into the soil through their root system.

In fact, there is several times more carbon in the soil than in the atmosphere. We could be collecting carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and directing it into oceanic and geologic repositories. There are no calculations available for this method yet, I think it would be a very expensive thing to do. But soil could be used as a repository too, that would be absolutely normal. That would improve the soil humus content and boost its fertility. Today we can say that the right process in agricultural production will definitely be able to stop carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere, and in the future, they can even begin to go down.

But that would require an entirely different paradigm of agriculture here. Today, food production relies on more and more machinery. The same machines burn motor fuel, emitting carbon dioxide, and compact the soil, reducing its fertility and humus content. In addition, farming agriculture and animal husbandry became separate industries: the pure organic matter no longer returns to the soil in the form of manure, the soil only gets mineral fertilizers, which are not fully used by plants.

If we make use of new technologies that eliminate active mechanical tillage, if we use crop residues as much as possible, along with manure fertilizers that allow the soil to live and breathe, enriching it with organic matter, if we use less chemical crop protecting products, then we will be able to overcome this trend. Everything is interconnected here.

– So, agriculture needs to go back to close cooperation between farming agriculture and animal husbandry, right?

– There needs to be integration. There should be none of those giant farms that have 10 to 20 thousand animals producing waste that they cannot possibly utilize and that, eventually, causes contamination and emissions. If we enrich the soil with bioorganic fertilizer, we will be able to increase yields, reduce emissions from animal husbandry, and improve the climate.

– Is it possible to breed a grain variety that would be least demanding to fertilizers?

– Our institute has long been working on this challenge. This matter is also connected to the problems of crop production, animal husbandry, and farming agriculture. If we practice crop rotation that includes perennial legumes, and if we use animal waste, it will be possible to use much less mineral fertilizers for plant nutrition. At the same time, crop rotations help with pest and plant disease control. There will be no need to use numerous chemical products to protect plants: the nature itself will be fighting these phenomena.

In addition, we are breeding grain and leguminous crops that will be resistant to the key profiling diseases. That is the objective of our Laboratory of Genetics and Pre-Breeding: they are creating donors that would be resistant to major diseases, such as brown and stem rust, powdery mildew. They will be protected from the disease at the genetic level. We can create varieties that will be resistant to adverse abiotic and biotic factors of the environment, and there are good prospects in that area.

Fertilizers are necessary, but it is important to follow the process: if you apply the right amount at the right time, you can reduce their use significantly.

– But it would be impossible to keep track of every manufacturer out there. If there is a commercial interest, one way or another some chemical fertilizers will be used at the wrong time, or with breach of the process...

– That is true, and this problem cannot be solved with prohibitive measures. We should cultivate a culture of farming agriculture, crop production, grassland management, and animal husbandry. First of all, it needs to reach manufacturers.

This is a complex issue of awareness. First of all, people need to know what they eat, how environmentally friendly their products are. Then consumers will put manufacturers under pressure to provide environmentally friendly or acceptable foods.

– So, there should be an agricultural awareness campaign?

– An awareness campaign too. We need a different, a new paradigm for the agricultural industry. Starting with training of various professionals.

The fact is that today, no one is training plant breeding professionals, they are worth their weight in gold. We are negotiating with many universities, hoping to resume cooperation. Universities should start training farmers, process engineers, and plant breeders that will then come to us for internships, that will learn from our academicians and continue to implement their knowledge in the fields of large farms and production facilities.

The classic variety breeding cycle lasts 10 to 15 years. That is why we want to organize a conveyor-like variety breeding process, so that every year, a new set would get ready. Our colleagues from Krasnodar have had success in this area, and we aim to achieve the same.

Director of the Nemchinovka Federal Research Center Sergey Voronov

– 2021 was particularly eventful in demonstrations of climate change: floods, extreme heat, extreme cold. Snowfall in early September in Yakutia. Are plant breeders prepared to face these climate changes? Do we have the time to produce new varieties that will be used in the industry?

– The climate will not change overnight, and plant breeding is based on environmental characteristics. We are creating drought-resistant, frost-resistant, and moisture-resistant varieties that will be able to withstand various adverse factors. It would be impossible to breed just one variety that would be able to withstand all of these factors. Different varieties are created for different environments, and we are gradually making our way up north.

Our varieties thrive as far north as Arkhangelsk Region, virtually everywhere, except the far north. Leningrad and Kaliningrad Regions have already become established areas of their cultivation. Of course, for the most part they grow feed grain, but still, all of our wheats, oats and barleys feel great in those areas.

– So, do you believe that despite climate change, there is no danger of famine because we have grains that will keep growing?

– Of course, there are high-quality varieties and seeds, but it is still not the time to relax. We must create new varieties of grains and legumes that would be more resistant to unfavorable abiotic and biotic environmental factors, and that will be in demand in agricultural production.

And the main thing is that we need to rearrange the mindset of both manufacturers and consumers, so that we all work for the same goal. Consumers should demand what they need, so that processors and manufacturers would figure out how to do their work without polluting the nature.

– Is the effort to change the agricultural paradigm and introduce new agricultural standards already underway?

– It is underway at the scientific level. We are working closely with the Ministry of Agriculture. We understand that we need to move in this direction and are developing certain plans for the restructuring of agricultural production. There is no schedule for those plans as of yet, but research is being carried out, and some studies have already been completed.

Photo: Andrey Luft, Scientific Russia

– British aristocrat William Amherst once said, “In the bad old days, there were three easy ways of losing money – racing being the quickest, women the pleasantest, and farming the most certain.” Do you agree with this statement in today's conditions?

– Today, agriculture is going through very difficult, challenging times, and it depends on several factors.

The first one is the devastating degradation of farmland soils; their humus content is going down. And this is the main factor that determines the yield and its quality. As a result, there is the climate change itself. This issue requires a comprehensive approach.

The main objective for agriculture is to be sustainable. It is a matter of the economy, the environment, and the social sphere: these three areas are interrelated. Unless we connect them all, unless we achieve a certain breakthrough in the minds of manufacturers and consumers, it will only get more difficult.

We understand that agriculture is an open-air workshop. It is constantly facing risks: coming from the climate, energy suppliers, our neighbors from abroad. It is a risky profession in general, but such is the human nature, especially in Russians, that we ignore risks and move forward with confidence in the future.