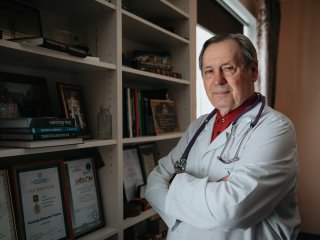

Alexander Grigorievich Chuchalin, Academician, Professor, a founder of the Russian pulmonology school, Chairman of the Bioethics Committee of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) and Head of the Department of Hospital Therapy in the Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University, talks about the doctor-patient relationship, bioethics, and ethical education in his interview with Scientific Russia.

― Should doctors be empathic? After all, there is a disease and the treatment guidelines for it. Why would we need human feelings here?

― To answer this question, we need to take a step back and look into history. The doctor-patient relationship changed just after the Nuremberg Military Tribunals. The Nuremberg Code was adopted following these tribunals in 1947. The first provision of this code dealt with patient voluntary informed consent. Therefore, the old world order was replaced by a new one with new doctor-patient relationships that rejected the paternalistic model, where doctors would independently make all treatment decisions following their own doctrine, without consulting either the patient or their family. The trial against Nazi German physicians prompted the world to create a special commission to analyze the crimes committed by doctors in that period. The principle of voluntary informed consent was adopted instead of paternalism. “Voluntary” means a serious and respectful attitude towards a person. If you do not respect your patient, do not treat them as an individual, and do not recognize their right to dignity, you violate the key provision of the Nuremberg Code that was adopted 75 years ago.

― What does informed consent mean?

― It is the ability to tell the truth. Doctors must explain all the pros and cons of medical procedures to their patients in simple terms, and it is only then that patients can decide whether to agree to a medical procedure or not. It should not be a mere formality. Today, I hardly imagine a situation where there would be no need for voluntary informed consent. This approach was adopted with great difficulty in global clinical practice, even in the Western world, where ethics committees appeared over 100 years ago. For example, now the United States has a special system for monitoring ethical issues in society. Here in Russia, we used to have a comprehensive moral philosophy. It was primarily rooted in the works of Nikolai Berdyaev who wrote a variety of philosophical treatises showing that ethics belongs to Human Sciences. Nikolai Berdyaev turned out to be a visionary in this sense. The Second World War started, we witnessed unprecedented atrocities against people, and the questions of human dignity and autonomy would soon become topical.

― Now people often talk about the implementation of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. What role will doctors play under this scenario? Will there be a need for direct interaction between doctor and patient?

― The 21st century is a time of new ethical challenges that fall into three categories: human genome editing, artificial insemination, and the above-mentioned artificial intelligence. During the pandemic, we have seen how quickly epidemiological data was processed using advanced technologies. Every week, we used to receive a new data set that was different from the previous one. New clinical guidelines were developed very quickly and so on. This is extremely important. However, no matter how perfect this entire system is, deep respect for human dignity is what really matters and this is where computer programs are powerless. Instead, it is the role of doctors that is important. Doctors’ human touch has a direct influence on patient recovery.

My student Igor Shubin has recently defended his dissertation in Saint Petersburg. The subject of his dissertation was “An Electronic Polyclinic.” The scientific council had a heated discussion on the role of a doctor in a scenario where a “machine” collects and analyzes data, creates certain formulas, and so on. What role would doctors play in this case? Don’t we need a doctor here? Of course, we need doctors, as they are responsible for the final part of this work, that is, for further linking the information to patients.

― One does not normally treat human dignity as a legal category in our society. Do you think it is possible to change this situation?

― Now we are raising the issue of ethical education. Let us reflect on how ethically educated our society is. Consider, for example, the recent vaccination case. There were serious issues: the principle of voluntary informed consent was violated, and paternalism emerged instead, “do it this way and not otherwise.”

― And it was relevant not only to Russia but other countries as well.

― Yes, you are right. This is a global problem, and, of course, it came up not only in Russia. It turned out that the principle of communication between doctors and patients that I have already mentioned today is quite difficult to implement in practice. Honestly speaking, the law lags behind the requirements advanced by modern ethics. A similar situation, for example, is found in the field of artificial insemination and human genome editing. Technologies have achieved progress, and they are introduced not only into scientific research but into everyday life, too, while the legislative aspect is underdeveloped. It lags behind. There is a lack of moral and ethical foundations for developing legislature.

― This brings us back to the question of bioethics. We already have the concept of human rights. Why do we need to introduce a new one? What is the difference here?

― The above-mentioned Nuremberg Code became the fundamental part of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The first provision of this code ― on voluntary informed consent ― laid the foundation for the subsequent development of the law. These documents formed the new world order. They should not be separated, as they influence one another. The Declaration of Human Rights and voluntary informed consent entail deep respect for human dignity, autonomy, rights, and freedoms.

As to your question regarding why human dignity is ignored, one of the key reasons for this is the poor ethical education in our society. After all, this education is not provided anywhere! Yes, some departments of medical universities give lectures on bioethics to junior students. However, these courses are short, while ethical education is lifelong education.

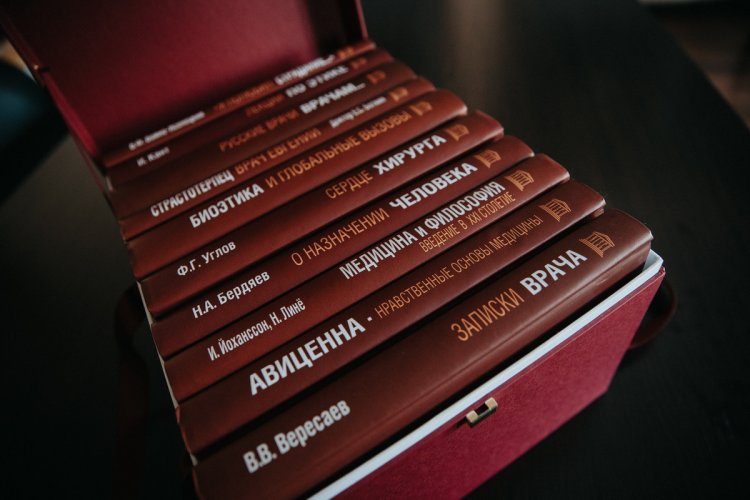

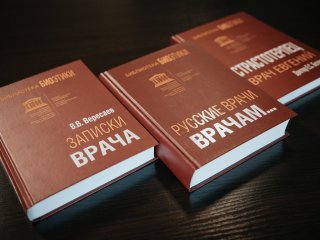

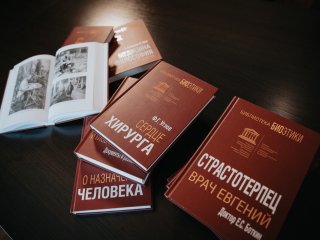

As the head of the clinic, I have been long preoccupied with bioethical issues. I monitor ethical issues and do everything possible to prevent violations of the above-mentioned basic principles. In addition, I have assembled a collection of works on this subject under the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) and UNESCO National Committee for Bioethics: this collection comprises ten volumes with fundamental works in the field. The collection includes books by previously mentioned Nikolai Berdyaev, the famous The Memoirs of a Physician by Vikenty Veresaev, my book Russian Doctors to Doctors, and many other works. At some point, I did a lot to canonize doctor and passion-bearer Evgeniy Botkin. In his books and lectures, Botkin raised the same questions you asked me. He said doctors must love and cherish patients.

― Doctors encounter suffering on an ongoing basis and, at some point, they might develop indifference towards it, that is, a sort of professional deformation can take place. How can this be stopped?

― We call this burnout syndrome. It happens not only to doctors but to people in other professions, too. Speaking about doctors, there are certain fields where this syndrome is more prevalent. First of all, this syndrome often attacks doctors who work with severe patients: these are doctors from resuscitation departments and intensive care units, as well as doctors working in red zones. We can hardly imagine the emotional strain imposed on them. It is a serious problem. Managers who understand this problem enable doctors to recover faster: for example, they create special recharge rooms. At some point, we were actively engaged in lung transplantation at Sklifosovsky Research Institute for Emergency Medicine. Their lung transplantation facility had a special room where surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nurses could drink coffee and tea, spend some time in a comfortable chair, and so on. These 10-15 minutes in such a recharge room were quite helpful.

Burnout prevention significantly depends on the administration of departments and clinics. As a rule, a doctor who suffers from burnout is very anxious, which inevitably affects their performance. Moreover, this is a “virus” that also attacks other colleagues. Therefore, managers should be able to understand this situation and take proactive measures to prevent a scenario where burnout turns into a serious problem affecting the team.

― How do you cope with burnout?

― What has always helped me is that I would always set new bigger goals and moved from one project to another. This approach has been quite effective. Therefore, my medical career is always a search for something new. For example, my team and I were engaged in lung transplantation, and this was an enriching experience. Interactions with students are of help, too. When I’m troubled, I go to students, start communicating with young people, deliver lectures or hold seminars. It helps me a lot because such communication neutralizes all negative emotions.

Doctors are vulnerable. No matter how brilliant you are, there will always be a person who will intentionally hurt a doctor’s feelings.

Sometimes, we monitor a patient for 20 years or more. It seems that we do everything possible to ensure that they feel well and can work, but then there comes a moment that was described by Vikenty Veresaev. Veresaev observed one girl for a long time. She was sick with severe pneumonia. She would get better from time to time, but then the disease would get worse. The girl’s mother would literally worship the doctor. However, then, the girl felt worse and died. Her mother started to hate the doctor. She used to glorify him and, in an instant, it all changed dramatically. Years and decades passed, and Veresaev’s trauma would eventually evolve into his famous book The Memoirs of a Physician. This book laid the foundation for the development of the WMA International Code of Medical Ethics. Books by Vikenty Veresaev have been translated into almost all languages in the world.

― You have been a doctor for many years. How has patient mindset changed over the years?

― Of course, people change under the influence of social, political, and economic factors. If we compare a contemporary patient and the one who lived 60 years ago, I see alienation in today’s patients. Patients are on their own, they do not receive any support or care. In a sense, these people feel lost and they are often depressed. They have no faith in recovery, and they do not believe in anything. Patients have become more complicated from a psychological point of view. At the time I am describing, everyone knew their GP, and the latter knew all patients, in turn. Now I cannot give an example of when a GP knows that their patient is admitted to the hospital, unless, this is a special hospital.

I believe that contemporary doctors need to master the methods of clinical psychology like never before. Today, empathy is the weakest aspect of the doctor-patient relationship.

Despite all difficulties, our society demonstrates highly positive attitudes towards healthcare professionals, and this profession is very popular with young people. We still see a high entrance competition in medical universities, in particular, in our Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University that has changed a lot in the last few years. The departments have been renewed, the medical equipment has improved, and so on. I am pleased to see how enthusiastically students are engaged in science in theoretical departments. This likewise creates a favorable atmosphere for applicants.

From the collection of works on bioethics.

Photo: Elena Librik / Scientific Russia

― Please tell us about your short-term plans related to bioethics.

― Thank you for asking. I have finished my work on the bioethics collection. Now I’m happy to make a gift to all our universities with the help of RAS. I would like every university to use this collection in their teaching. It would be great if universities realized the importance of teaching bioethics in all courses and created special interdisciplinary programs. A person with a medical degree must know that ethical education is something that must continue across the lifespan. I want doctors to have such an opportunity: if something is unclear, take a volume with the works by Vikenty Veresaev, read the books by passion-bearer Evgeniy Botkin or study Embraced Martyrdom by Luka (Voyno-Yasenetsky) that describes it all brilliantly. It is through suffering that doctors understand their patients. No matter how qualified you are, ethical problems are always acute and accompany doctors throughout the whole life course.