Aristotle once said: “We can trust our senses, but we can still be easily deceived by them.” The philosopher noted that if you look at a waterfall for a long time and then turn your eyes to the mountainside, the rocks seem to move in the opposite direction to the flow. This phenomenon is now called in science the motion aftereffect. By focusing on the water stream for a long time, our brain neurons adapt to this movement of signals in the same direction. Therefore, after moving our eyes to the stationary mountains, we still see motion, but in the opposite direction.

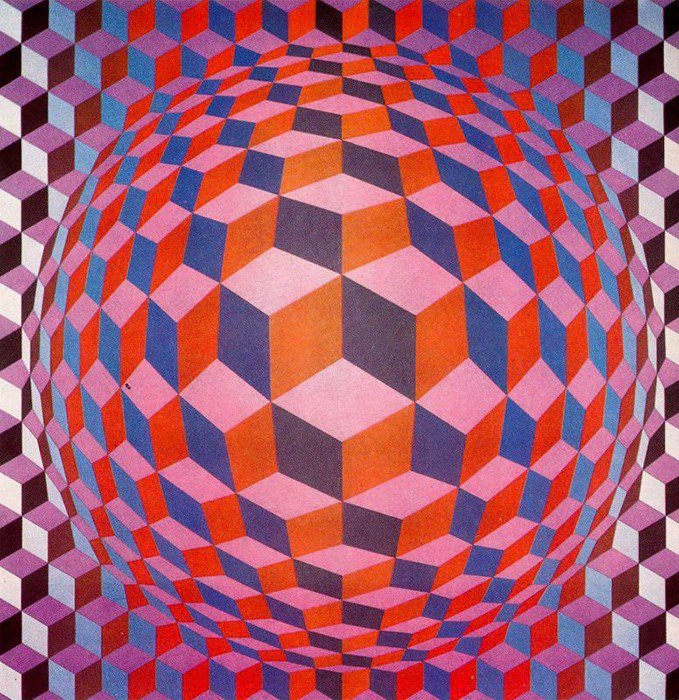

In general, optical illusions do not imply an imperfection of the visual system. Everything happens in the brain, which receives information from the retina and transforms it. And sometimes unexpected things happen. Scientists use these visual “traps” to study the peculiarities of perception, because we see one thing, but look at something completely different. For example, when we look at this flat image, we see a three-dimensional picture:

Neurophysiologist Michael Bach explained that optical illusions are a direct evidence of the perfection of our visual system. Its most important properties are consistency or constancy. That is what deceives us in this strawberry illusion:

These properties suggest that the berries are red – this information is fixed in the brain. So, in all cases, except for this picture, it will work. Thanks to constancy, we see, for example, that our palms are the same when one palm is close to our face and the other is outstretched.

The first studies of visual perception began in the second half of the 1940s. At that time, scientists came to the conclusion that under certain conditions, reality can be seen differently. Then they realized how vision could be deceived on purpose. Such practices found their way into art, architecture, and painting. They began to create “deceptive” spaces, technical objects.

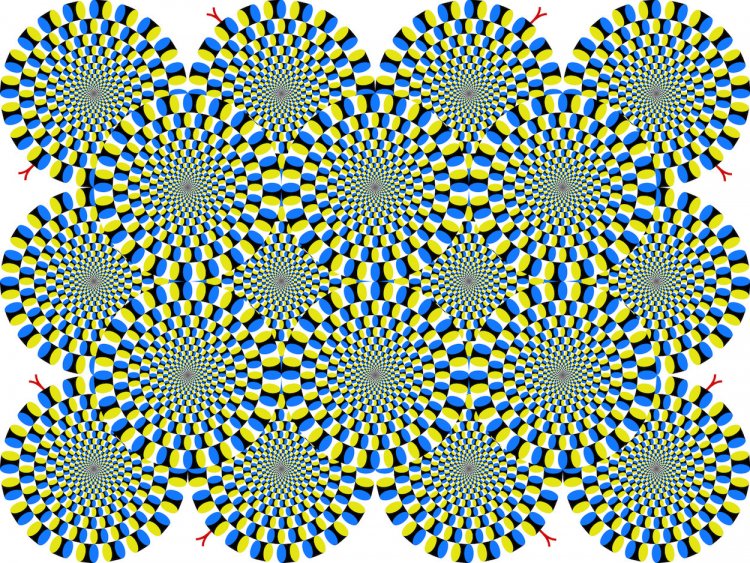

For example, in the early 2000s, Akiyoshi Kitaoka created an illusion of movement with the help of the “Rotating snakes.” The essence of the technique is that when you look at the “snakes,” you involuntarily think that you are looking at a video, not at a static picture. But the movement only happens in your mind.

The technique secret is to alternate spots of different brightness in a prescribed sequence: yellow, white, blue, black. And when asymmetry is added, the image begins to “float.” The illusion is created by the brain regions that process information about brightness, contrast, and movement.

It works this way: due to the bright contrast between black and white, the brain's neurons are quickly activated. And the difference in color between blue and yellow causes smoother and longer activity of the corresponding neurons. When two groups of neurons are simultaneously activated, the visual cortex neurons that take part in motion recognition get involved.

But not all people see the picture moving – about 5% of people are immune to the Kitaoka effect.

So, optical illusions turned the world and its perception upside down, even at an early stage. Nicholas Wade, a specialist in the history of optical illusions at the University of Dundee in Scotland, said: “By creating illusions, scientists realized that even understanding of the eye mechanism does not provide a complete picture of the nature of vision.”

In the 1950s, a new trend in art called op art (from the English “optical art”) emerged. One of its founders was artist and sculptor Victor Vasarely.

Being aware of the human eye's mechanism of perception as regards flat and spatial figures, artists, sculptors, and designers began to create their masterpieces.

Their object perception is based on an optical illusion: the image surprisingly “lives” in several dimensions at once: on the canvas, in the eyes and in the mind of the audience. Colors from contrast to soft, melting in halftones; geometric drawings: dots, lines, curves, spirals, it all helps create such works. They are overlaid on each other, which creates the effect of “secondary images.” And the task of op art is to deceive the eye by drawing something that does not exist in reality through the conflict between the actual form and what we see.

The op art artists violate the norms of human perception. Scientific research has shown that the eye always “puts in order” scattered spots, building them into a coherent system. This is opposed by optical art, where the elements are scattered chaotically. They confuse the eye, preventing it from building a coherent structure. It is not difficult to imagine what happens to the viewer's nervous system at exhibitions where moving, glowing, reflecting light and glare systems were exhibited. The viewers complained of dizziness and fainting, and not from the impression received from the artistic images at all.

Photo on the homepage: gifer

Photo on the page: nevrologica