How did the life began on the Earth? Was it born on the planet or brought from the space? Why did it develop in the way it did? Can it happen that humans disappear from the face of earth once? Can it be avoided? These are the topics of our conversation with Sergey Vladimirovich Rozhnov, head of higher invertebrate laboratory at the Paleontological Institute of RAS, RAS academician.

– Sergey Vladimirovich, why do you deal with higher invertebrate?

– The laboratory of higher invertebrate is a conventional, traditional name for the one dealing with Echinodermata, brachiopod, bryozoans, etc. However, even the latter name does not accurately reflect the group that we study. I have additionally taken a postgraduate for corals and a student for sponges. These are very interesting fossil organisms. Why have I taken them? The Russian school of coral specialists was the most famous in the world. Yet, almost all of them have gone away with time. Some of them left science for natural reasons, others switched over to other groups.

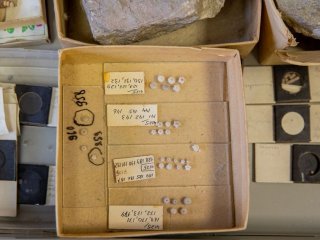

However, large collections remained, and we have to support this research area.

– You study ancient organisms finding samples representing these or those organisms in various corners of the globe. How profoundly have you advanced? Which are the most ancient organisms that you have discovered?

– All these organisms have been known since the beginning of geological history of the Earth. It is approximately 3.8 billion years. However, we face challenges, related to definition in the first turn. These are bacteria which transform in tiny petrified balls, extended chains and similar formations. It is hard to identify them, as these are organic residues of primitive organisms. One can find very little of morphology there. As for younger sediments, academician Aleksey Yurievich Rozanov suspects to find in them the remains of more advanced organisms.

– Can you say when the animals that inhibit the Earth today first appeared?

– It is an interesting question. The most interesting thing is that the first animals looking like the modern ones appeared in early Cambrian period, about 540 million years ago. All types of animals existing today came into being very quickly during the Cambrian period.

– Why did it happen in the Cambrian period?

– It is serious problem. The process is called Cambrian explosion evolution, and there are many different assumptions. First of all, their ancestors came up to some landmark in morphological and genetic development, which allowed for producing an explosion of morphological diversity. Even Darwin said that what happened in the Pre-Cambrian period was a great mystery. Nothing was known about it. However, in the second part of 20th century, the scientists found the remains of many different creatures in Pre-Cambrian deposits. The problem is that they bear no resemblance to the animals living in the Cambrian period and ones existing today. It is a serious problem how to relate them to each other. There are various assumptions, but cannot reach common ground so far.

– Do you mean that it was a different world with different creatures?

– Yes. Some scientists try to prove that, say, the shellfish is one of them. Another one looks like corals. The third one bears resemblance to nobody. Some scholars ranked them among echinoderms. Yet, in case of detailed examination, they can hardly be reckoned among these or other known groups.

– What is the crucial distinction that makes them different?

– First of all, the majority of them have no skeleton. As for the Cambrian period, many skeletal animals appeared in it.

– Yet, there are creatures having no skeleton even now. Are they the descendants of the Pre-Cambrian animals?

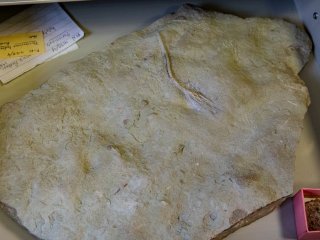

– No. The fact is that the existing creatures without skeleton are absolutely different. Let us take Chenyang Cambrian fauna in China – they find the imprints of non-skeletal organisms there. They are also diverse, yet bear no resemblance to Cambrian ones, and vice versa – you will not meet non-skeletal organisms from the Pre-Cambrian period in the Cambrian one. However, they find today samples having skeleton, yet it is not clear what period they belong to, as their skeletons are starkly different from the ones which came to existence in the Cambrian period.

– What do you think happened during the Cambrian explosion? Why are the creatures which started originating after that differ markedly from the previous ones and are not their descendants?

– We do not know for sure whether they are their descendants or not. They must be, but relating them to each other constitutes a serious problem. The fact is that adult organism comes of a tiny larva. These larvae are not found in fossil state, as they are hard to be discovered due to small size. That is why it is hard to compare juvenile stages, the ones that other organisms could have originated from.

– What are the variants? What could have changed? Might it be atmospheric composition or anything else?

– Naturally, it might. First, the concentration of oxygen rose substantially. Second, the chemical properties of seas changed a lot. A certain balance was established as to the oxygen concentration in the atmosphere and the sea. Yet, where does the atmospheric oxygen come from? At that time, it came from the sea. The first metazoans on the land appeared in the late Ordovician and Silurian era, i.e., much later. The oxygen was coming from the water thanks to, first, algae and – which is the main thing – cyanobacteria which could live both at the sea bottom and in water depending upon the conditions. So, they could float and sink to the bottom covering it with biofilm and thicker bio-tufts.

These cyanobacteria tufts and films disengaged a lot of oxygen. This oxygen would saturate the water and come into the atmosphere. The oxygen concentration in atmosphere might have been low, yet there were places, oxygen oases where there was enough oxygen for existence of active animals.

So, they had to first appear in these oases and later inhabited the whole planet, when the oxygen concentration in atmosphere grew. It was in the Cambrian period that a boom in lifeform development was observed. It happened due to positive feedback among animals, plants, and various biotic communities.

What was the main event to happen in the Cambrian period? Those bacteria and single-cell animals which lived in the upper layer of water could not sink to the bottom due to their tiny size.

– They were too light, weren’t they?

– First, they were too light. There is a phenomenon called thermocline in seas. When the upper layer of water gets warm, the temperature changes very quickly with depth. The organic matter that existed near the water surface could not sink deeper due to inability to clear the thermocline.

The Cambrian period gave birth to filterers, bigger larger animals. They started filtering these tiny organisms. They were substantially bigger and their fecal pellets could sink to the bottom. The bottom became rich in these organic materials, which gave birth to benthic organisms.

– There were no such animals in the Pre-Cambrian era, were there?

– We find benthic animals in the Pre-Cambrian deposits. However, they were tied to cyanobacteria tufts and shallow depth, where they lived. The Ordovician is the next after Cambrian period. Now, I mainly deal with the Ordovician era. The Ordovician evolutionary radiation is related this period.

– Are the Ordovician creatures the descendants of the Cambrian ones?

– Sure. There are no doubts about it. They also differ in structure, yet fit into the general structure type of the Cambrian creatures that we know.

– So, no mysteries here, right?

– There are a lot of mysteries. Yes, we know them to be the descendants of Cambrian animals. However, if we take any type of specie, there may be very many transitional forms within it. Sometimes, it is even hard to distinguish between species. As for higher taxa, even starting from the level of family, order and class, it is very hard to find transitional forms between them. We actually cannot find them, and have to assume.

Having a look at the phylogenetic trees that paleontologists build, you will see lines which are connected with dotted lines at the bottom. We just assume that some creatures bear resemblance to the other ones in some attributes, yet the paleontologists fail to find any transitional forms between the groups. Thus, there are a lot of mysteries.

– I would like to skip to humans. Is it clear where man has evolved from, or do we also see dot lines here?

– There are many dot lines here, but we have genetic analysis and evolutionary biology of development. However, we traditionally do not study humans at the Paleontological Institute. That is why I can tell you nothing new.

– You are not interested in human being as a specie, right?

– Yes, we do not take interest in man to a large extent. Other people and institutions deal with this topic, though paleontologists sometimes find individual fragments like teeth of ancient people and describe them. However, man is not our specialty.

– You have mentioned the Ordovician evolutionary radiation. What is it? Did the sunshine become more intensive?

– It has nothing to do with solar radiation. Evolutionary radiation means divergence of characters in contrary directions. It is the period when biodiversity became much more pronounced. I.e., we have a flattened curve standing for the rise in biodiversity which begins to go up dramatically starting from the mid-Ordovician. The species diversity and number of families increased dramatically, and new classes of animals came to existence. It is interesting that we see no classes of sea animals to come to existence after the Ordovician period, while there were no new types of animals after the Cambrian era. Put it differently, we see lower level and richer diversity.

– I.e., the evolution produced some classes and species which are optimal for further existence, didn’t it?

– More precisely, a certain structural plan developed. It impeded the ability of other plans to develop. At the same time, the adaptive traits started to appear easier, while the diversity was growing within the framework of the same structural plan.

– Why did it happen this way?

– As for benthic animals, I have a theory of positive feedback between benthic community and hard ground. The fact is that special ground with hard objects is required to enable the animals’ larvae to settle at the bottom, as the majority of larvae are floating. In the Pre-Cambrian period, the slime ground accounted for the major part of ground, and there were few hard objects – well, maybe some individual shells. The larvae had to settle for further development and therefore required some hard object at the bottom.

What happened in Ordovician era? New echinoderm classes emerged, for instance crinoids, cystoids featuring very high calcite productivity. Their skeleton consisted of very many elements which were porous and easily destroyed. After their death, immense quantities of calcite detritus were left, which led to development of cyanobacterial tufts and films in many places. These films would catch small calcite detritus, bind and cement it with glycocalix – an adhesive agent. Thus, hard ground was formed after the die-away of cyanobacterial tuft. The community of benthic organisms with calcite skeleton would settle on this ground and produce even more of detritus. It was a sort of positive feedback: the increase in the number of areas with suitable ground where communities of benthic organisms with calcite skeleton would settle led to the rise in quantities of detritus, so the grounds changed dramatically in the Ordovician Period.

It is not by chance that we can find very many limestone layers in Ordovician Period deposits. Moreover, these are bioclastic limestone interlayers. The ground changed dramatically, and it resulted in evolutionary radiation.

In late Ordovician period glaciation followed. Glaciation always results in a part of ocean water being transformed into ice which, in its turn, leads to the drop in ocean level. It was the time of a large ice sheet in Gondwanaland (contemporary Africa).

– Did glaciation take place in Africa?

– Yes, very powerful one. We still find the traces of this glaciation there. The water level in oceans dropped drastically, and peripheral shallow seas, which are fit for animal life most of all became very narrow. The animal life immediately started relocating to either the depth or land. In the Silurian era, the plants and algae limited to shallow waters began to develop on the land thus leading to the genesis of sophisticated plants.

What happened in the seas? Many groups of organisms just became extinct. Later, the glacier melted, and new shallow seas emerged. They were populated by the descendants of organisms which had settled here back in the Ordovician Period as accessory ones. Their descendants became dominant organisms, and the composition of sea biota changed dramatically again.

Then, several critical periods followed. The most important event happened on the cusp of Paleozoic and Mesozoic (the cusp of Permian and Triassic), when many animal groups became extinct, and the diversity reduced drastically. The recovery began starting from Triassic, and the so-called Mesozoic fauna – both marine and terrestrial one – arose.

However, the plants had conquered the land before that. In the Devonian period, the vegetation was mature enough. Consequently, other animals – four-footed ones in the first turn – started to settle on the land. These animals cropped up in the Devonian period.

– Sergey Vladimirovich, now we see global warming again. Do you think that a new explosion will happen, and the humans may be replaced by other creatures which are not our descendants?

– I do not think so. Man is a creature of great vitality. We should be afraid of being suffocated by our wastes instead of some new creatures which are to replace us. Academician Zavarzin, an outstanding microbiologist developing a special research area – environmental microbiology – introduced the notion of cacosphere (derived from Greek word cacos meaning wastes).

– Is the well-known word derived from it (Russian slang word for feces)?

– It may be so. Before his death, the scientist published a book titled Cacosphere. This problem looks extremely serious, and it is not clear how to solve it, as people consume increasingly more and produce not only life wastes which bacteria can decompose. The main hazard lies in what is around us, the techno-sphere, accommodation for living, etc. I mean these plastic things in the first turn. It is not clear how to solve this problem. Our country has recklessly adopted the western way of life. We have quickly learned how to make beautiful packing, yet failed to find a method of processing and recycling it. The same is true for batteries. We are active in using them, but try to hand them in for recycling. It is a problem indeed.

– Do you think that life on other planets might choose a different way of development? Take Avatar for instance – the highly intelligent inhabitants of this planet can boast of supernatural abilities like levitation, telepathy, etc., as they have preferred spiritual development to technological one…

– Well, such ideas are pure science-fiction. Naturally, paleontology like astronomy invites to such thoughts. Life might have probably begun on other planets and taken different forms…

– Moreover, there are scholars, including academician Rozanov, academic director of your Institute, who is convinced in life having been brought to the Earth from space.

– Yes, it might have come from space. Yet, what kind of life? So far, we find only primitive remains of this life and no traces of sentient creatures. There is no evidence of any advanced forms of life comparable with human one. Neither paleontologists nor astronomers can find it. However, paleontologists sometimes like to indulge in fantasies.

By the way, paleontology is closely related to developmental biology today. The latter science deals with the mechanisms of an egg giving birth to an organism and morphogenetic processes that take place inside it. Biologists are interested in how morphogenetic mechanisms have been changing over geological periods. They have to rely on paleontology in these studies, so the demand for paleontology as biological science is rising dramatically today.

– Looks great! As far as I have understood, you are sympathetic towards ecological problems and back the ideas of your brother, outstanding ecologist, academician Vyacheslav Vladimirovich Rozhnov, director at the Institute of Ecology and Evolution.

– It is so. We do care about ecological and evolutionary problems. By the way, there is such science as paleoecology, a very popular one today. Its roots are at the Paleontological Institute, which generally accepted. The founding father of paleoecology is Roman Fedorovich Gekker, who worked at the Paleontological Institute and died in 1990.

– How can one family produce two academicians at once? What should be done for it?

– I have never thought of becoming an academician. I have even never thought of serious career. Even the position of laboratory chief did not appeal to me.

– Nevertheless, you have become not only a laboratory chief, but deputy director of a research institute as well…

– Sure, but such a career has never appealed to me. The aspiration for scientific achievements is one thing, but a managerial position requires such abilities, as getting along with people, handling them, being a leader, etc. I have never had such inclination.

– My question was not about administrative position. I mean that both of you are academicians and outstanding scientists. How did your parents manage to bring up such sons?

– Actually, we were not brought up for this. We sprang from common people. The fact is that my father was heavily wounded during the war and then developed tuberculosis. He went off to war a youngster and came back a sick man, so my mother had to look after him. It was a hard time, so I do not even want to recall it. The life was hard.

– How did you take interest in science?

– I am pretty surprised myself. Naturally, there were some conversations with my father. He was a passionate and talented person. But for the war, he would have become an outstanding scholar too. Yet, the war rocked his world.

– Why did you choose paleontology?

– I wanted to become a geologist, as the romance of travels lured me. When I was in the fifth form, I decided to enter the Geological Faculty of MSU after having talked to my father. Then, I found out about a geological group under the MSU. Though, only older kids were admitted, they turned a blind eye to my age and enlisted me. I took interested in the lessons. Once I met Anton Erlanger at an open-cut mine near Moscow. He collected fossil organisms for factory Nature & School and built up paleontological collections for schools and universities. He was carried away with this occupation. So Erlanger started telling us about paleontology. His lecture is still vivid in my mind. He showed moss animals and something else to us, and I suddenly felt interested.

At that time, book Paleontology Course by paleontologist Davitashvili came out. It was very interesting and written in excellent Russian language. I bought this book in summer and would not even come out until reading it over. My friends left Moscow for summer camps, while I rode a bicycle to the Moskva River and started picking up ammonites, belemnites, etc. Using this book, I managed to define and classify my findings.

– So, you were carried away by live geology…

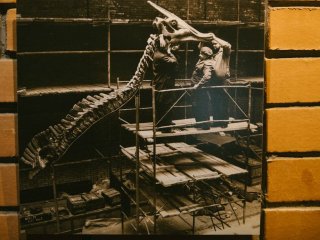

– Yes, live geology and revitalizing paleontology. I used word revitalizing, because paleontologists virtually revitalize extinct organisms studying them. As for zoologists, they kill live organisms to study them. Thus, we complement each other. Later, I continued my studies at a Pioneer Center as a member of geological group. After the eighth form, I entered a specialized geological school. Having finished it, I entered the Geological Faculty and chose the department of paleontology there. When I was a student, the paleontological department was actually my second home. Thus, I devoted to paleontology the whole of my life.

– You do not feel sorry for it, do you?

– I have never felt sorry for it. I have left offices and deal with science alone. I am still carried away by science as much as in my youth. The students and postgraduates are around me all the time. They look for somethings and find it. Even amateur paleontologists hand interesting samples over to me. This is the way we work.

Interviewer: Natalia Leskova