Scientific Russia continues publishing a series of articles dedicated to the natural wealth of Karelia and development of science in the region. Earlier we have already told you about the Karelian Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Kivach Nature Reserve and the Girvas paleovolcano. Today we will introduce the unique Karelian petroglyphs – the UNESCO world heritage sites.

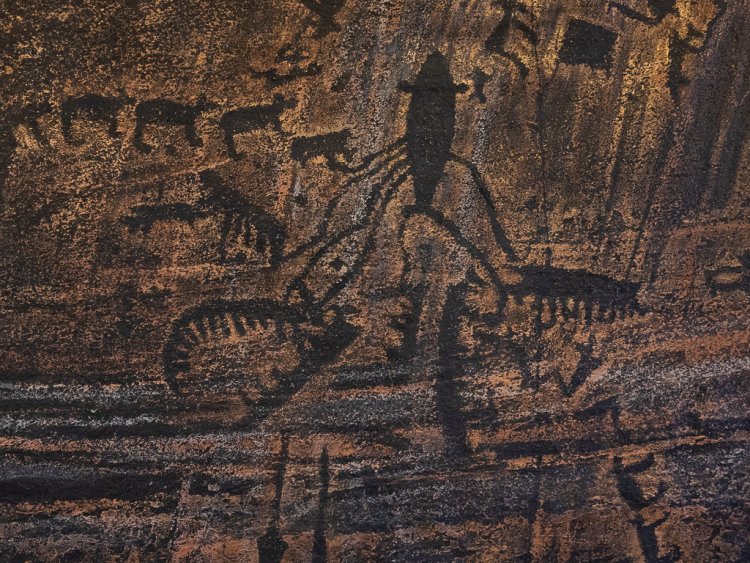

In ancient Greek, the petroglyph means carving on rock (petra ─ rock, stone, glyphe ─ carving). These images engraved or painted on stone are considered one of the oldest extant art forms. The age of such drawings (found all over the world) sometimes reaches 40 thousand years.

Karelia has preserved unique examples of primitive Neolithic rock art (their age is 6-7 thousand years): some of the White Sea and Onega motives and stories have no analogs in the world. In 2021, these images carved on Karelian granites were included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. Thanks to the efforts of scientists from the Karelian Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, these petroglyphs are known all over the world today.

“When we were writing an application to include the Karelian petroglyphs in the UNESCO World Heritage List, we were unable to find other objects similar to ours to compare them. These monuments really have no analogs. The voting took place practically without discussions, as the uniqueness of the Karelian petroglyphs was obvious to all members of the commission. Some of them were very surprised to find out that our petroglyphs had not been included in the UNESCO World Heritage List yet,” said Senior Research Associate at the Archeology Sector of the Institute of Linguistics, History and Literature at the Karelian Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences Nadezhda Lobanova.

The petroglyphs are carved on the hardest Archean crystalline rocks ─ granitoids. This is the reason why the drawings in the stone have preserved almost in their original version.

The Onega petroglyphs were discovered on the capes and islands of the eastern shore of Lake Onega in the mid-19th century, while the White Sea ones ─ on the islands of the River Vyg, not far from its confluence into the White Sea, in the first quarter of the 20th century.

“It is noteworthy that the appearance of the White Sea petroglyphs was triggered by the Onega ones. There were contacts between the inhabitants of the two territories located at a distance of over 300 km from each other. I believe they even practiced pair-bonding, as there are almost identical images. Besides, we are finding new confirmations of this interrelationship. The White Sea and Onega petroglyphs are included in the UNESCO World Heritage List as a serial object that has two components. This is the first time when we have managed to reliably prove the cultural, environmental and chronological relationship between them. <...> The petroglyphs are planar art, but only on the Karelian rocks ─ in the White Sea region, we see examples when artists tried to convey volume and movement, they also dexterously used the micro-relief and color of the rock surfaces to create a polychromous effect (on Lake Onega). These facts alone give grounds to include the Karelian petroglyphs in the UNESCO World Heritage List,” said Nadezhda Lobanova.

Senior Research Associate at the Archeology Sector of the Institute of Linguistics, History and Literature at the Karelian Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences Nadezhda Lobanova talking about the Karelian petroglyphs.

One can see the impressions of petroglyphs, or close life-size contact copies, at the Karelian Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Petrozavodsk artist and petroglyph researcher Svetlana Georgievskaya recreates rock drawings on black rice paper. She used the traditional Chinese copying technique to invent an author’s method of making embossed estampages with due account for the local peculiarities of the rocks and the large size of the embossed drawings. This technology is unique, quite laborious and time-consuming, but it allows defining the outlines of half-erased, indistinguishable petroglyphs on a paper surface, clarifying their contours and even displaying small details inside the embossed drawings, which has provided new opportunities of studying rock drawings.

“Before embossing an image in rock, ancient artists used to analyze it first: what hillocks, depressions, fractures or color spots it had. Then they tried to fit their drawing into them, as if weaving the drawing into the natural “picture” of the stone, or even creating a story based on them. For example, one of the rock drawings featured a beluga whale at that point of the rock where water was flowing from the top of the soil layer after rain. Thus, the artist created a feeling that the beluga whale was swimming in a stream of water. The distinctive peculiarity of the Neolithic artists of the White Sea region was their attempt to show the dynamics of their story in time, that is, they did not fix any particular image, but tried to clearly tell the entire story,” said Svetlana Georgievskaya.

Artist and petroglyph researcher Svetlana Georgievskaya talking about the Karelian petroglyphs.

What do we see in the embossed drawings by primitive artists? Usually they are hunting scenes or images of individual animals, as well as everyday scenes. They especially liked to portray swans, elks, beluga whales, and bears. However, their flight of fancy was not limited only to routine scenes from their life. The Stone Age artists also used to create mythological stories that resemble abstractionists’ paintings. One of these images located at the tip of the Besov Nos Cape being two and a half meters in size is a mysterious anthropomorphic figure.

Christian monks called this figure “The Demon” in the 16th century, and this disharmonious name stuck for many future centuries. Svetlana Georgievskaya says that this is “The Great Mother,” a characteristic image of the Stone Age. Her sculptures are found throughout Eurasia. In our north, she is carved on a flat rock. Her extremely stylized shape, expressive pose also personify kind of an extraterrestrial force, divine essence that gives birth. The same cape also has other amazing anthropomorphic characters ─ more modest in size, but equally amazing.

The Lake Onega petroglyphs also created a huge number of images of celestial bodies: the Moon and the Sun, completely mysterious images, as well as signs that we cannot unambiguously interpret at the moment.

Today, we know at least 1,200 figures and signs carved into the rocks and stones of Lake Onega. Most of them are located in the territory of three capes on the eastern shore of Lake Onega: Peri Nos, Besov Nos and Kladovets Nos. The collection of petroglyphs from the Besov Nos Cape is among the most interesting collections in Fennoscandia that attracts tourists and scientists from all over the world. Scientists from the Karelian Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Scandinavian countries and other European states come to the territory of the Lake Onega and White Sea petroglyphs every year with their archeological expeditions. Today, some fragments of Karelian rocks with petroglyphs are kept at the Hermitage: both in the main exposition and in its funds.

To preserve and multiply the natural and cultural wealth of Karelia is a Karelian scientists’ objective for the coming decades. Next time we will tell you about the unique mountain park Ruskeala. Stay with us!