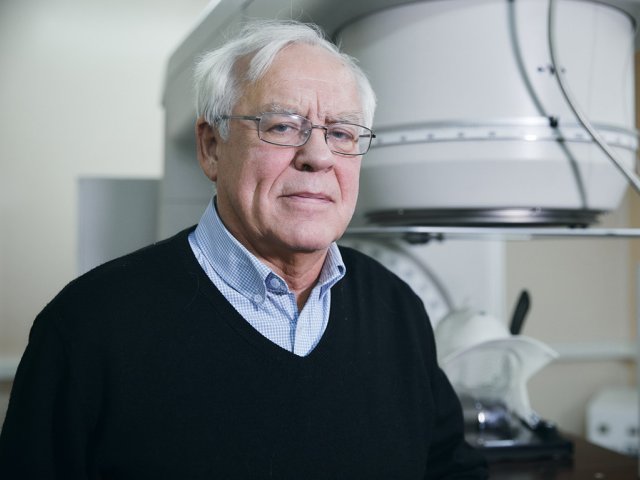

July 31, 1912, is the birthday of Milton Friedman, an American economist and the laureate of the Nobel Prize 1976 for “for his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy.”

Friedman’s professional and scientific career could be compared to a skyrocketing stocks yield curve of some major Wall Street bank. But let’s begin from the beginning.

Friedman was born to a family of East European Jewish immigrants. He said once that his father had tried to succeed in hopeless trade transactions and failed. That probably had some influence of the future successful economist.

Friedman was 16 when he started his studies at Rutgers University, and in 1932, he was awarded bachelor's degree in both economics and mathematics. As a student, he met two influential economists: A.F. Burns and H. Jones. Thanks to the latter, Friedman received a recommendation to go to the University of Chicago to continue his studies, where he subsequently earned his master’s degree.

After the fellowship at Columbia University where he continued postgraduate studies, Friedman returned to the University of Chicago in the fall of 1934 to work as a research assistant. Eventually, the economist stayed in Chicago for a long time, but this time as an economics professor with a PhD degree.

In 1950, Friedman was involved in the implementation strategy of the Marshall Plan as an advisor; he defended the idea of floating exchange rates in Paris. Friedman knew what was going to happen well before the crush of exchange rates under the Breton Woods Agreement in the 1970s.

Milton Friedman became a prominent adherent of monetarism – an economic theory. His studies focused on the structure of income and consumption, money circulation, issues of “human capital” and contradictions of economic stabilization. The economist opposed any government interference in the economy.

The essence of his scientific views was that consistent monetary policy should be abandoned since it would lead to cyclic fluctuations anyway, while constant money supply expansion would be a better option. According to Friedman, the optimal money supply growth rate in the economy should be 4% a year.

Along with Anna Schwartz, Friedman analyzed the role of money during various historical cycles. They offered their conclusions in the following works: Monetary statistics of the United States, 1970 and Monetary trends in the United States and the United Kingdom, 1982.

With regard to the Great Depression, the researchers write: “The Great Contraction is tragic testimony to the power of monetary policy-not, as Keynes and so many of his contemporaries believed, evidence of its impotence.”

According to Friedman, “it’s all about money,” because changes in nominal income growth rates are caused by changes in money supply growth.

However, Friedman believed the Theory of the Consumption Function to be his main achievement, whereby people’s behavior is based on their expected income rather as opposed to their current income.

Photo on the page and the homepage: Milton Friedman (Wikimedia) + drawing of polling place, 1891, from Alexander L. Peterman (Wikimedia)