Official:

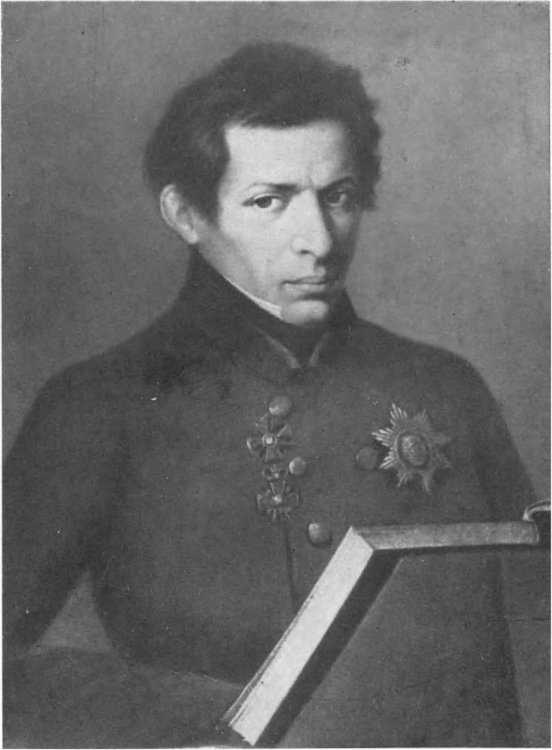

Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky. November 20 (December 1), 1792 –February 12 (24), 1856. Russian mathematician, creator of non-Euclidean geometry.

Life and Work:

1. After studying Lobachevsky’s biography, Veniamin Kaverin came up with a pun that he lived two parallel lives. On the one hand – a respectable and recognized official, and on the other – an unrecognized genius.

2. In 1832, the Hungarian mathematician Janos Bolyai invented a new geometry that completely refuted Euclid’s one. He sent the results of his work to the great German mathematician Johann Karl Friedrich Gauss. But the latter did not accept his invention, accusing Bolyai of being not original. The king of mathematics at the time insisted that such ideas had already been published by the remarkable Russian mathematician Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky in 1829-30.

3. They called Lobachevsky Copernicus of geometry. Meanwhile, Lobachevsky had absolutely no intention of turning anything over. It just happened that the world-renowned Russian scientist wanted to prove the Euclid’s fifth postulate, but refuted it instead. And a different geometry emerged.

4. Little is known about the future great scientist’s parents and childhood. It is still debated who was the famous mathematician’s father. The most likely version is that Nikolai Lobachevsky’s father was an official of the Nizhny Novgorod land survey office, Ivan Maksimovich Lobachevsky. Nikolai was the middle of Praskovya Alexandrovna Lobachevskaya’s three sons; her husband died in 1800.

5. Lobachevsky’s father worked in a land survey office, that is, he was a surveyor. In other words, he measured land. His son also became a surveyor of a sort, because geometry means “to measure land” in Greek.

6. Before revolutionizing geometry and earning worldwide recognition, Nikolai Ivanovich received a good education and made a quick prdsgogical career.

7. In 1802, Nikolai and his brothers entered the Kazan Gymnasium with a state scolarship. At that time, it was the only gymnasium in the entire Russian Empire to the east of Moscow.

8. While Nikolai Lobachevsky was grinding away at his high school studies, especially excelling in mathematics and foreign languages, Emperor Alexander I signed papers on opening a university in Kazan.

9. It turned out to be a fateful decision: Lobachevsky gave Kazan University forty years of his life.

10. Wonderful tutors took care of the poor, yet talented student, but narrow-minded authorities hated him: in his senior years, Lobachevsky was attributed with “dreamy self-conceit, stubborness, disobedience,” “outrageous acts,” and even “signs of godlessness.”

11. The tutors stood up for him, and the gifted student was not expelled from the university. On the contrary, he was awarded master’s degree in physics and mathematics cum summa laudae and got a job at the university.

12. Lobachevsky’s career took off at quick pace: he was under twenty-two years of age, when he became a scientific assistant; at about thirty he became a professor, infinitely appreciated by students. Then he was appointed dean of the Department of Physics and Mathematics, and at the age of thirty-four he was elected rector of the university.

13. Nikolai Pavlovich Zagoskin, the historian and rector of Kazan University in 1906-1909, lauded his predecessor’s work. He called Lobachevsky “the great builder” of Kazan University.

14. Indeed, Lobachevsky did a lot as the head of Kazan University: he erected new buildings, mechanical workshops, laboratories, and an observatory. He greatly contributed to replenishing the library and the collection of minerals. Due to Rector Lobachevsky’s efforts, Kazan University became one of the best educational institutions in Russia: reputable, well-equipped, and renowned for its excellent faculty.

15. Working as a professor, dean, and then rector, Lobachevsky taught courses in geometry, trigonometry, algebra, mathematical analysis, probability theory, mechanics, astronomy, and hydraulics. He was an educator as well: this great scientist often delivered popular science lectures for Kazan residents.

16. His scientific career was not so smooth. His geometry textbook for high schools was severely criticized for using the seditious metric system invented in rebellious France, while his algebra textbook was not published at all.

17. The revolutionary non-Euclidean geometry was not recognized in Russia; the Academy of Sciences issued a negative resolution, while the Syn Otechestva journal sarcastically wrote that it lacks not only scientific nature, but also basic common sense.

18. However, the great Gauss appreciated it: at an old age, he undertook to learn Russian in order to study Lobachevsky’s works.

19. Non-Euclidean geometry is a huge, but not the only Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky’s contribution to mathematics. Independently of the Belgian mathematician Germinal Dandelin, Lobachevsky developed a method for approximate solution of equations, clarified the continuous function concept, wrote works on trigonometric series, and proposed a sign of numerical series convergence. Yet, this list of his scientific legacy is far from exhaustive!

20. In 1832, Lobachevsky married Varvara Alekseevna Moiseeva. His wife was almost 20 years younger than the scientist. Seven Nikolai Ivanovich’s and Varvara Alekseevna’s children survived.

21. In 1836, the emperor paid Kazan University a visit. Nicholas I was satisfied with what he saw and awarded the rector the Order of St. Anna, 2nd class. The order gave the right to hereditary nobility. It was granted to Lobachevsky two years later. The matematician’s noble coat of arms depicts a golden star made of two triangles and a golden bee, as well as a silver overturned arrow over an overturned horseshoe.

22. In 1846, Lobachevsky’s 30-year term of service in the Department of Public Education expired. According to the charter, the department had to make a decision regarding the continuation of his service. Contrary to the university council, which unanimously re-elected Nikolai Ivanovich rector for the sixth term, Lobachevsky was dismissed from the rector’s position as well as his chair.

23. Misfortunes haunted the elderly scientist. He went bankrupt, and his house in Kazan, along with his wife’s estate, was sold to cover the debts. Lobachevsky, who was already blind, dictated his last work, Pangeometry, to his students in 1855.

24. Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky died exactly three decades after he presented his geometry to the world for the first time.

25. The university in Kazan was not named after Lobachevsky. In 1925, Kazan University received the name of its most famous student – V. I. Ulyanov-Lenin. In 1956, Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky’s name was given to the university of his native city, Nizhny Novgorod, which bore Gorky’s name at the time.