The study of inclusions in amber from Myanmar by the specialists of FECIAR UrB RAS (Arkhangelsk) is devoted to specifying the data about the fauna species of Chalk Period founded in resin. The paleo-reconstruction of ancient stone borer’s habitat provides new insight into Mesozoic Forest ecosystem, in which amber was formed, while the representatives of invertebrates can be viewed as a credible point of calibration for building evolution models

The gallipot still holds many more secrets to give up. Amber as a fossil form of organic compounds can allow one to gain insight into the evolution of life on the Earth providing information about primeval creatures and climatic changes that took place on the planet. The animal and plant organisms enclosed in the resin, or inclusions, are invaluable from the viewpoint of scientific discoveries.

Such unique findings containing many relict groups are abundant in the amber from Myanmar (South-Eastern Asia).

Within the framework of state project Species Formation in Fresh Waters – Role of Regional and Global Geological Processes (state registration number AAAA-A18-118012390161-9; period from 2018 to 2021), the biologists from Arkhangelsk-based FECIAR UrB RAS studied the samples of Myanmar amber extracted in the pits located not far from the village of Tanai, in the north of the country. The stone-borer that had lived millions of years ago and was found in the amber prompted the scientists to set the question of this creature belonging to freshwater species. Having reconstructed its habitat and performed a comparative analysis, the specialists uncovered its relation to the contemporary Lignopholas rock-borer. The data obtained will let the scientists reconstruct a credible picture of freshwater population that lived on the territory of South-Eastern Asia in the Chalk Period and get explanations as to their life in neighborhood with sea species. The research results have been recently published in SCIENTIFIC REPORTS, 11, 1-14, 2021 (Nature Publishers).

Ivan Nikolaevich Bolotov – doctor of biology, RAS correspondent member, director of the Laverov Federal Center for Integrated Arctic Research of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Arkhangelsk), head of Molecular Ecology and Phylogenetics Department at the Northern (Arctic) Federal University

Project manager Ivan Bolotov, doctor of biology, RAS correspondent member, director of the Laverov Federal Center for Integrated Arctic Research of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Arkhangelsk), Head of Molecular Ecology and Phylogenetics Department at the Northern (Arctic) Federal University (Arkhangelsk), told a story of how the inclusion of ancient stone-borer of Chalk Period found in fossil resin of araucaria family trees complements the evolutionary picture of the world.

First of all, the scientist explained what makes the amber from Myanmar (fossil resin of araucaria family trees) unique, and why a lot of fauna representatives were found in this very amber:

“Burman amber from the state of Kachin in Myanmar is a petrified witness of biodiversity typical for the Chalk Period. The age of this amber is about 100 million years. It has no equals in the number of inclusions contained as well as the level of their preservation. Over the past decade, the interest in studying the Burman amber on the part of scientists has risen dramatically. As of 2020, the representatives of 42 classes and over 1,500 species of living organisms including animals, plants, fungi, and microorganisms have been found in the amber. It is the richest fauna of the Chalk Period among the ones we know on the Earth. Every year, dozens of articles devoted to the description of new taxons from Burman amber are published. Over the past years, the scientists have made such unique findings, as the hatchling of ancient Enantiornithean bird, tail of a dinosaur cub, as well as frogs, lizards, and geckos sealed in the amber form Myanmar.

It was the resin of araucaria family trees (or the one of cypress for some locations) that served as a source of Burman amber. Until recent time, it has been believed that the ancient coniferous forest was growing on the sea coast. The evidence of it lies in the findings of sea fauna in amber – shells of stone-borers, as well as small ammonite shells and several specimens allegedly being sea shrimps. However, the Burman amber is much richer in freshwater fauna, like dragonflies, caddis flies, mayflies, stoneflies, Chironomidae species and other inhabitants of rivers and lakes. Recently, a shell of freshwater pond snail (Lymnaeidae) has been discovered in this amber. On one of the beetle species sealed in amber, the scientists discovered water-lily dust – a clear evidence of the amber forest growing near some freshwater ecosystems.”

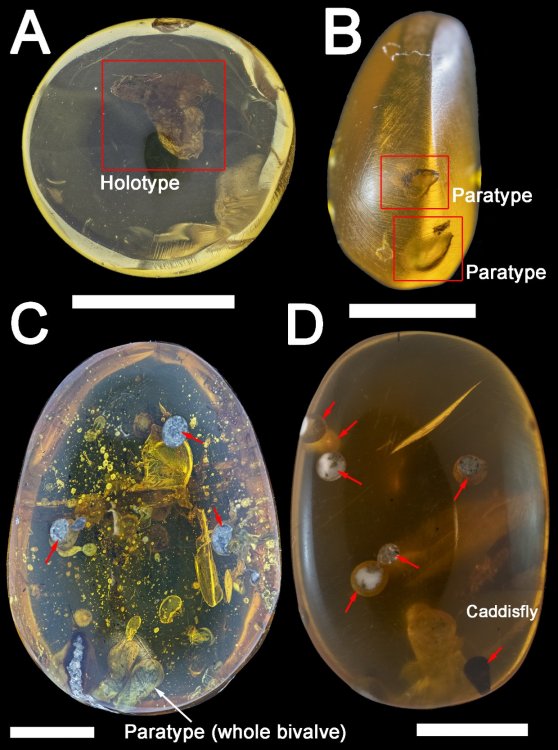

According to Ivan Bolotov, “for many years, the clear inconsistency, i.e., discrepancy between the abundance of freshwater fauna and presence of numerous remains and traces of stone-borers in the same samples of Burman amber have made the scientists perplexed. About a year ago, the American colleagues turned to us with a request to pay attention to these stone-borers found in Myanmar amber and try to reconstruct their habitat. The fact is that the stone-borers (the ones of Pholadidae family) do not belong to the popular groups of living organisms, and few scientists are aware of them in taxonomic respect. There are no such specialists in the United States. Following the result of our research, SCIENTIFIC REPORTS journal (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-86241-y) published an article. In this paper, we describe a new type and specie of stone-borer belonging to the Chalk Period. We have studied a series of nine relatively small samples of Burman amber. The length of these polished pieces varied between 8 and 33 mm. (see Fig. 1).”

Figure 1. Samples of Burman amber with shells (red squares) and traces (red arrows) of stone-borer Palaeolignopholas kachinensis from Chalk Period (isotope dating of the amber rock’s age is 100 million years). The white arrow points to the completely petrified mollusk specimen. 5 mm scale rules.

Photos: Ilya V. Vikhrev

What is the evidence of the fact that the mollusks found themselves in the resin alive?

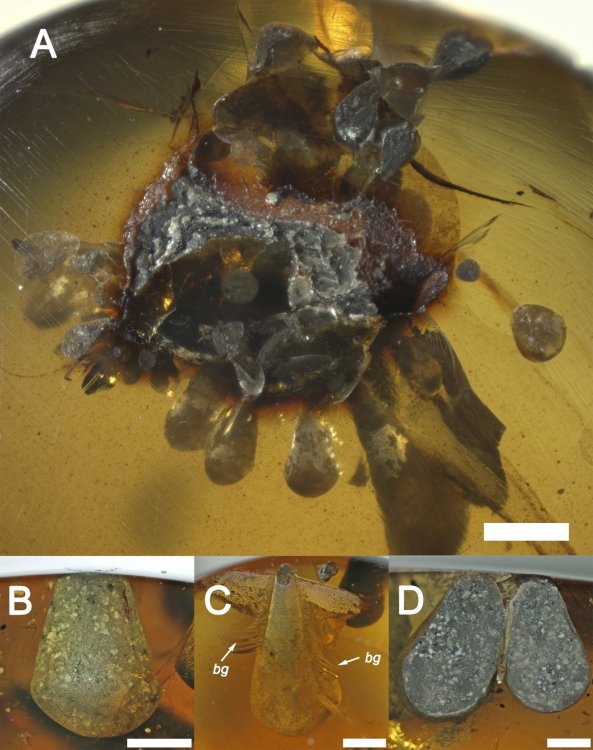

“The resin often turned out to become a sort of ecological trap for stone-borers. The mollusk would penetrate it easily drilling the consolidated outer layer and get stuck in the liquid resin inside. Thanks to this circumstance, their shells would be permeated with resin and reach the present time almost intact. They were as if floating inside the amber (see Fig. 1, 2А). Some of the mollusks just petrified in their traces having preserved the outer structure of the shell (see Fig. 2В). In both cases, the samples can boast of a wonderful level of preservation for the age of 100 million years and allow for describing even the fine details of the shell structure (see Fig. 3). Sometimes, the stone-borer larvae would penetrate a piece of wood or plant stem which would later get stuck in a drop of resin. In these cases, the traces of stone-borers fan out around the plant inclusion (see Fig. 4А). Sometimes, we can see the so-called bioglyph – a typical trace formed by rotation of mollusk’s shell around the longitudinal axis in hardening resin (see Fig. 4С),” the scientist explained.

Figure 2. Resin impregnated shell floating in amber (А) and petrified undamaged specimen (В) of stone-borer Palaeolignopholas kachinensis. The fine structure of the shell surface is intact though the age of shell is 100 million years. 0.5 mm scale rules

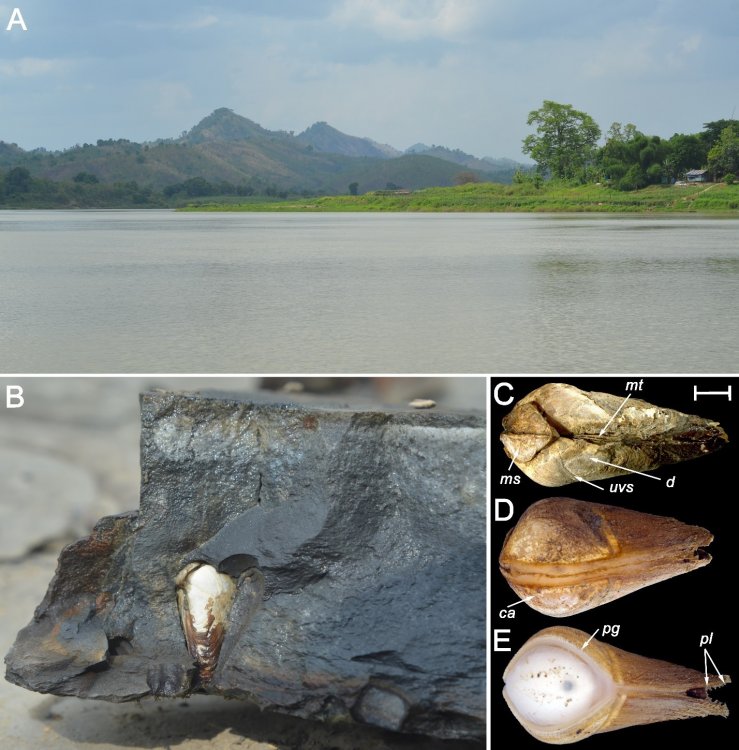

In the course of research, as Ivan Bolotov stressed, “it was found that primeval stone-borers are close enough to the contemporary Lignopholas species that usually live in the estuaries of tropical rivers in Southern and South-Eastern Asia. They can drill tunnels in wood, brick masonry, and some types of silicate rock (argillite and siltstone). As minimum, two contemporary species of Lignopholas can live in fresh water today. These are Lignopholas rivicola and Lignopholas fluminalis. The latter specie was found in fresh water for the first time. Its freshwater population lives in the Kaladan River located in the state of Rakhine, in the north-western part of Myanmar (see Fig. 5). The article about this discovery – the first evidence of macro-bioerosion – was published in NATURE COMMUNICATIONS journal (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-05133-4).”

Figure 3. Schematic reconstruction of stone-borer Palaeolignopholas kachinensis. To the right – adult specimens (А – side view, B – top view, C – bottom view), to the left – juvenile specimens (D – bottom view, Е – top view). F, G – mesoplax, triangular plate at the top of the shell, an important part for identifying stone-borers (F – adult mollusk, G – juvenile mollusk). 1 mm scale rules

Figure 4. Traces of stone-borer Palaeolignopholas kachinensis in Burman amber. At the top – mass penetration of mollusks into the resin from the wood fragment or araucaria root (А). At the bottom – penetration of mollusks directly into the resin (В-D). Alphabetic notation bg stands for the so-called bioglyph, typical trace of the mollusk shell’s rotation around the longitudinal axis in hardening resin (С). 1 mm scale rules

What are the special features of this ancient specie (features common for both amber stone-borers with the one living in Myanmar today)? What affords ground for making a conclusion that the discovered ancient stone-borer was the ancestor of all contemporary rock-borers of Lignopholas type?

«Both the ancient stone-borer and contemporary Lignopholas species have biforked mesoplax. It is a special triangular plate in the top part of the shell protecting the connection point of shell plates from damages during the drilling of substrate. The majority of other stone-borer groups have an integral mesoplax, not a biforked one. The general design of the shell structure is similar for both ancient and contemporary stone-borers to a great extent. However, the ancient mollusk from the amber is different from Lignopholas, as it has a distinct concentric sculpture in the form of ribs on the shell surface and different structure of periostracic lamellas – special outgrowths on the upper layer of the shell. That is why we ascribed the amber stone-borer to a special type, new for science – Palaeolignopholas, which we consider to be the probable ancestor for contemporary Lignopholas. As for its specific name – Palaeolignopholas kachinensis – the ancient mollusk was named after the state of Kachin in Myanmar, where the amber deposit is located.

It is interesting that all discovered species and traces of Palaeolignopholas feature small sizes – less than 1 cm in length. The most of current species are much bigger – 2-3 cm in size. One of the reasons of this difference may lie in the early death of mollusks which found themselves in the amber. On the other hand, one of the current species (Lignopholas chengi) from the island of Borneo (Kalimantan) also features small dimensions – up to 1.2 cm in length,” the scientist specified.

The specialists of FECIAR UrB RAS performed regional paleo-ecological reconstruction aimed at the identification of ancient stone-borer to verify the preliminary assumptions as to how the freshwater species of invertebrates found themselves in the resin of the trees growing on the sea coast.

“Initially, we assumed that the ancient stone-borers may be morphologically close to one of the typically marine genotypes. However, when it turned out that the ancient stone-borer is likely to be the ancestor of currently living Lignopholas species, it became clear that the amber mollusks’ habitat might be located in the estuary or low reach of rivers. Their habitation in stagnant water bodies like lakes or dead arms of rivers is hardly likely. The degree of salinity in the upper part of estuaries or lower part of rivers may vary dramatically depending on the season, tidal rise, etc. – from fresh to briny water. Meanwhile, the high diversity of freshwater fauna in Burman amber – dozens of species of dragonflies, mayflies, caddis flies, and so on – is the evidence of low salinity degree. Yes, all these creatures can be met in the river estuary, but in the conditions of basin with briny water, these groups will never be so rich in species, as was registered in Burman amber. In general, a collection of facts points out that the ancient coniferous forest was likely to grow in the lower reach of tropical river instead of sea coast. In the article, we suggested the river of Kaladan inhibited by current freshwater stone-borers Lignopholas fluminalis (see Fig. 5) as possible (though faraway enough) analog of Mesozoic ecosystem with Palaeolignopholas species living in it.

As for the question about the origin of scarce marine species found in Burman amber, it is more difficult to interpret. For instance, we have found a small ammonite shell there. Ammonites belong to the marine group, though there is evidence that they might live in waters with different degree of salinity changing their habitat in the process of growth. By the moment of getting into the amber, the ammonite had already been dead, while its shell was full of sand. It is not unlikely that the mollusk could be transferred from the sea coast on the claws of an Enantiornithean bird or brought to the river valley by a strong wave. The ostracod and isopod shrimps discovered in amber might have been the representatives of estuary fauna penetrating into the low reach of river during high tides,” Ivan Bolotov explained.

According to the scientist, “100 million years ago, the part of Myanmar where the amber deposits are located was a tropical island lying in equatorial latitudes. It is a fragment of Indian continental plateau, i.e., a fragment of ancient supercontinent Gondwanaland comprising India and the southern hemisphere continents – South America, Africa, Australia, and the Antarctic. Subsequently, the river inhabited by Palaeolignopholas species and other fauna might be located relatively near the sea, though the amber deposits are now far from the sea coast.”

Figure 5. Habitat (A), traces (B) and shells (C-E) of freshwater stone-borer Lignopholas fluminalis, which lives in the river of Kaladan in the western part of Myanmar. It is assumed that Palaeolignopholas kachinensis discovered in the Chalk Period amber is a distant ancestor of current Lignopholas species. 2 mm scale rule

What main conclusion can be made as to identifying the habitat of ancient stone-borers found in amber? What can this information offer to us (for instance for understanding the special features of ecosystems existing at that time)?

“The main thing that we managed to show is that the mollusks and their traces cannot serve as clear indicators of marine conditions that sediment accumulation took place in. It is very important, because the specialists viewed Palaeolignopholas as an element of marine fauna alone before our paper was published. As the traces and shells of this type of stone-borers account for the majority of inclusions in Burman amber and can be met in its many samples, it was considered as the main evidence of the fact that the ancient forest was located on the sea coast.

Now, it has become clear that the araucaria forest was growing in the lower reach of river, instead of sea cost. The resin would drip down in abundance from the tree branches hanging over the water. The branches, trunks, and resin of araucaria trees falling down into the river would become a substrate for the settlement of stone-borers. Their larvae penetrated directly into the resin or fragments of dead plants which had got into it. The new data that we have obtained allow for viewing the Mesozoic Forest ecosystem where the amber was formed from an absolutely different angle.

One of the key moments that lie behind our interest in fossil mollusks and other organisms that Burman amber contains is the possibility of using them as credible calibration points for evolution models. In particular, the decoded nucleotide sequences of individual genes, mitochondrial genomes, and entire genomes allow for building phylogenetic trees demonstrating the evolution of these or those groups of species. In order to place the phylogeny into time scale, one can use the method of molecular clock. If the evolutionary rate of these or those genes is known, this parameter can be built in the model, and the specialist will get the phylogeny reflecting the course of evolution in time at the output.

However, the average values of genes’ evolutionary rate vary among different organisms. For the mollusks that we are talking about, they may be different by dozens of times. That is why it is better to use precisely dated fossil findings for the calibration of phylogenic purposes, as they are easier built in the model nodes. The samples found in the Burman amber having the age of about 100 million years represent a unique archive of such calibrations for various groups of animals and plants due to their high level of preservation. Amber samples usually keep a set of morphological characteristics that allow for identifying the fossil organism accurately enough, as well as its approximate position in this or that phylogenetic clade.

There are no doubts that Mesozoic Palaeolignopholas species can well be used for calibration and will help us understand better the evolutionary history of stone-borers in general in future,” the director of FECIAR UrB RAS summed up.

Thus, the study of fossil genotype of stone-borer mollusks found in Burman amber provides the evidence of the fact that their habitat might have been in the freshwater conditions, and finally introduces a point of clarification into the concept of Chalk Period ecosystems.

Source of all drawings represented here by Ivan Bolotov: article Bolotov, I. N., Aksenova, O. V., Vikhrev, I. V., Konopleva, E. S., Chapurina, Y.E.; Kondakov, A. V. (2021) A new fossil piddock (Bivalvia: Pholadidae) may indicate estuarine to freshwater environments near Cretaceous amber-producing forests in Myanmar. Scientific Reports, 11, 1-14.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-86241-y