Crimean researchers have put the main focus on Russian literature of Crimea from the period of the Revolution and the Civil War, which has played a major role in understanding the historical literary process in Russia

There were various research approaches and opinions in Russian and foreign science to understanding the phenomenon of Russian émigré art and the contribution of the Russian diaspora to the world literature. One reason for this may be the fact that Russian writers – scattered over the world and isolated from their birthplace – were committed to preservation and development of Russian culture.

Crimea became the place of incredible spiritual and creative inspiration for Russian writers and poets just before they lost their home following the pivotal events in the early 20th century Russia. It was a place of reflection on the state of Russian society on the eve of huge societal cataclysms, on the fate and paths of the country. A number of programmatic works that became classics of Russian and world literature were written in Crimea.

Scientists of the Institute of Philology, History and Art at the Academy of Humanities and Education Science (branch) of Vernadsky Crimean Federal University in Yalta, jointly with their colleagues – literature experts and museum workers – conduct long-time research looking into art of Russian 1st Emigration Wave writers that were somehow connected to Crimea. In fact, Crimea is considered a starting point for the exodus of Russian creative community in the 20th century.

Svetlana Sergeevna Tsaregorodtseva, Candidate of Philology,

Svetlana Sergeevna Tsaregorodtseva, Candidate of Philology, Docent of the Department of Russian and Ukrainian Philology with Teaching Methodology at the Institute of Philology, History and Art at the Academy of Humanities and Education Science (branch) of Vernadsky Crimean Federal University in Yalta, has been studying history of Russian literature of the 20th century, which includes the works of Georgy Dmitrievich Grebenschikov, a writer and public figure unjustly forgotten by history of Russian émigré art.

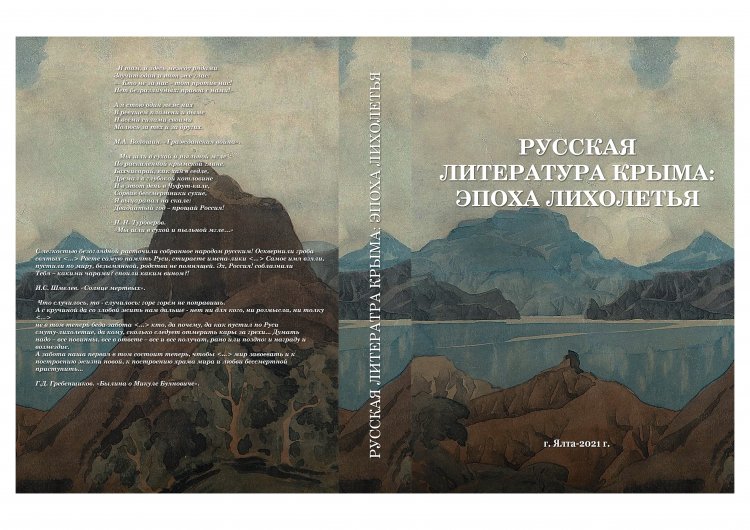

The literature history expert spoke of results of her colleagues’ research on writers and poets in Crimea during the Revolution and the Civil War, which is the collective monograph RUSSIAN LITERATURE OF CRIMEA: THE TROUBLED ERA. This project received a grant from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR) and will be released by the end of 2022. Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva also referred to Georgy Grebenschikov’s creative journey since before his “Odyssey,” he was witness to the tragic conflicts that changed Russia's path and were a subject of artistic interpretation and evolution of opinions in Russia’s literary community.

“This year, the Department of Russian and Ukrainian Philology with Teaching Methodology of the branch of Vernadsky Crimean Federal University in Yalta, received a considerable sign of appreciation for our longstanding work – as a support from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR) we received a grant for RUSSIAN LITERATURE OF CRIMEA: THE TROUBLED ERA project to publish a collective same-name monograph. The idea came up in Simferopol about three years ago. As we spoke to Oksana Vladimirovna Reznik, Doctor of Philology, Vice Rector for Scientific Work at the Crimean University of Culture, Art and Tourism, we remembered that some very memorable dates for Crimea were approaching: the Civil War, the Exodus, and the outcome of the war, which essentially ended in Crimea. We were talking of how much the Russian writers who resided or stayed in Crimea during the period contributed to artistic interpretation of that complex and contradictory epoch, background factors and consequences of the troubled era, and found numerous parallels with the modernity. Our monograph is most important for history of culture for it tries to answer many relevant questions. The monograph is the result of long-time and systematic work: our department has held several conferences, which helped us understand this tangle of issues and build a creative team of the monograph’s authors. We held a conference dedicated to the 150th anniversary of M. Gorky, and several national conferences, such as the conference Literary Travelog: Crimean Vector in 2019 and 2020. In fact, all writers, starting from Pushkin, were incredibly inspired by Crimea and produced works, important for both Crimean and Russian literature. Some of those works have been undeservedly forgotten. For instance, there is the novel Beast from the Abyss by Y. Chirikov, or the Epic Ballade of Mikula Buyanovich by G. Grebenschikov where the latter answered the question of what happened in 1917 and how the Russian people have to wash away the sins they committed at that time,” said Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva as she spoke of new aspects revealed by the current research in Russian literature of Crimea of the Revolution and the Civil War periods, and how they help understand and accept that troubled era, which became pivotal for Russia.

The cover of the collective monograph RUSSIAN LITERATURE OF CRIMEA: THE TROUBLED ERA, designed by Aleksandr Rykhlevsky, a student of the Academy of Humanities and Education Science

The central chapter of the collective monograph RUSSIAN LITERATURE OF CRIMEA: THE TROUBLED ERA is focused on Maksimilian Voloshin. The chapter was written by Sergey Mikhailovich Pinaev, Doctor of Philology, Professor of the Department of Russian and Foreign Literature at RUDN University, a renowned Russian researcher and author of a book within the Lives of Remarkable People series (2005).

“Books by S. M. Pinaev as well as by O. I. Fedotov, S. O. Kuryanov and A. P. Lyusy now serve as textbooks for our philology students. S. Pinaev believes that Voloshin’s work is the crossing of all paths of the Silver Age, and that his civic stand in the troubled era was to be “above the battle” and pray for “both sides.” Maksimilian Voloshin is the creator of Kimmeria, a big historical and cultural myth,” Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva remarked. The editorial board believes that this chapter on Maksimilian Voloshin is the monograph’s locomotive.

The book also includes publications by other colleagues from Moscow. For example, Oleg Ivanovich Fedotov, a specialist in verse poetics from the Moscow Pedagogical State University (MPSU), provided two chapters: “The Black Sun over Crimea” on the book The Sun of the Dead by I. S. Shmelyov, and “Crimea in Nabokov’s Poetic Evolution” on the experience of an 18-year old Vladimir Nabokov who learned a lot as a poet in Crimea – the themes of his Crimean verse also take place in his mature poetry and prose. Svetlana Anatolievna Makarova, Doctor of Philology, a specialist in musical verse poetics, wrote the chapter “On the approaches to the Sivash Battle: aesthetic self-determination of I. L. Selvinsky during the height of Russian modernism.” Aleksandr Pavlovich Lyusy, culturologist, literary critic, Doctor of Philology, journalist, the founder of the concept of a Crimean text, provided the chapter “The Rise from Taurida to Kimmeria, or the Union of Rivieras: Crimean text of the early 20th century.”

Nonetheless, most of the authors of the book are Crimean specialists from the Crimean University of Culture, Art and Tourism (Simferopol), the branch of Vernadsky Crimean Federal University (Yalta), as well as the Institute of Teaching Education and Management (branch) of Vernadsky Crimean Federal University (Armyansk), the Memorial House of A. P. Chekhov (Yalta), and the Yalta Literature History Museum (Yalta).

Two chapters – “The Inexhaustible Chalice: Ivan Shmelyov and the Crimean Tragedy” and “The fate of Chekhov's legacy” – were provided by the expert Crimean researcher Gennady Aleksandrovich Shalyugin, Candidate of Philology, Member of the Writers' Union of Russia, and a former Director of the Memorial House of A. P. Chekhov in Yalta. Yelena Yurievna Lisitsina, Candidate of Philology, senior professor at the Humanities Department of the Institute of Teaching Education and Management, wrote the chapter “The Crimean myth of the holy land in M. I. Tsvetaeva's poem Perekop.” Based on letters and documents from the collection of the Memorial House of A. P. Chekhov in Yalta, Yulia Georgievna Dolgopolova wrote the chapter “A. P. Chekhov and Y. N. Chirikov: Crimean encounters.” Tatiana Nikolaevna Barskaya, a journalist from Yalta, wrote the chapter “The Crimean biography of the play Lyubov Yarovaya (Spring Love) by K. A. Trenyov (Meeting the prototypes).”

Remarkably, many chapters of the book contain information from archives, including those that are virtually inaccessible for Russian specialists (such as the Central State Archive of Kyiv). For example, the chapter “Chervony Zapev by Grigory Petnikov” written by A. D. Temirgazin, a researcher from Feodosiya, magically contains data from such valuable archive sources.

B. K. Tebiev’s chapter contains numerous new and fascinating facts on V. V. Veresaev and N. Tuverov; the chapter by A. V. Lyulikova, Candidate of Philology, is about the Crimean text by M. Bulgakov; the chapter by experts of L. M. Ivanova’s Yalta Literature History Museum is on Gorky’s stay in Yalta; and O. A. Kopyl’s chapter focuses on the playwright S. A. Naidyonov. N. I. Nikonchuk (Yalta) chose theater as her topic; her chapter is called “Kachalov’s group: the road back home (the 1919-1922 tours).”

The plan is to publish 300 copies of the monograph RUSSIAN LITERATURE OF CRIMEA: THE TROUBLED ERA, and send them to central libraries across Russia, where readers will be able to learn about the Russian scientists’ research on the literature of the first wave of the Russian scattering.

The book has a few pages on the Yalta Chekhov Literary Society (YALO), which existed till 1922, and held gatherings attended by 100 to 150 people: literary figures, painters, theater people, literature experts, and scientists. According to Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva, “such creative communities as well as artistic anthologies they composed are evidence of the literary process in Crimea at the time.” For example, there was the Crimean anthology Otchizna (1918), which featured fiction by Chekhov, Korolyenko, Shmelyov, Sergeev-Tsensky, and Trenyov, articles by Yelpatievsky and Derman, as well as Bunin’s poems.

In his anthology review published in the Nasha Gazeta newspaper in Yalta, Grebenschikov writes that a selection of 15 poems entitled The Book of Travel “takes us to boundless spaces of earthly beauty and joys.”. Grebenschikov called Shmelyov’s novella The Inexhaustible Chalice a milestone marker, which helped the author “complete all significant and profound artworks he had created so far.” He compared the novella to Nesterov’s canvases, which also depict the strength and greatness of the Russian spirit, the willingness to sacrifice and forgive. Among the prose mentioned by Grebenschikov, there is the short story Mix by Sergeev-Tsensky, “a great writer of all Russia.” Grebenschikov believes that novels, novellas and short stories by Sergeev-Tsensky are worth being read carefully, so that a critic or reader would feel their integrity, artistic merits, and moral power. According to Grebenschikov, the best works by Sergeev-Tsensky are The Sadness of the Fields, Babaev, Bailiff Deryabin, and the Depths. In 1922, the Yuzhny Almanakh was published, with the Crimean poems by M. Voloshin, B. Nesmelov and B. Pasternak, prose by V. G. Korolenko, and V. V. Veresaev, an extract from the play Pugachovism by K. Trenyov, the article by V. V. Lvov-Rogachevsk “Gamayun, the prophetic bird: in memory of A. A. Blok”, and war memoirs. “We can see that Crimean publications constantly featured leading Russian writers and critics,” Tsaregorodtseva concludes.

Georgy Dmitrievich Grebenschikov (1883-1964). Writer, critic, journalist, public figure

Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva has been doing research on Georgy Dmitrievich Grebenschikov’s work for many years; she defended a thesis on the topic: “THE NOVEL THE CHURAEVS BY G. D. GREBENSCHIKOV IN THE SOCIO-CULTURAL CONTEXT OF THE ERA.” Scientists became interested in the writer back in the 1990s, when after a long time, literary magazines published extracts from Grebenschikov’s autobiographical books Yegorka’s Life and The Messenger. Letters from Pomperag.

For the collective monograph, Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva wrote the chapter “The Crimean journal and fiction by G. D. Grebenschikov in 1918-1922.” The Crimean scientist pointed out that “there are totally unjustly forgotten works with stories based in south Russia and Crimea. Our goal is to show those wonderful texts, which usually took a back seat in literary research. As the literature expert A. A. Makarov said, “When we were getting I. Bunin, I. Shmelyov, and A. Remizov back from emigration, we left out the best of them – G. Grebenschikov.”

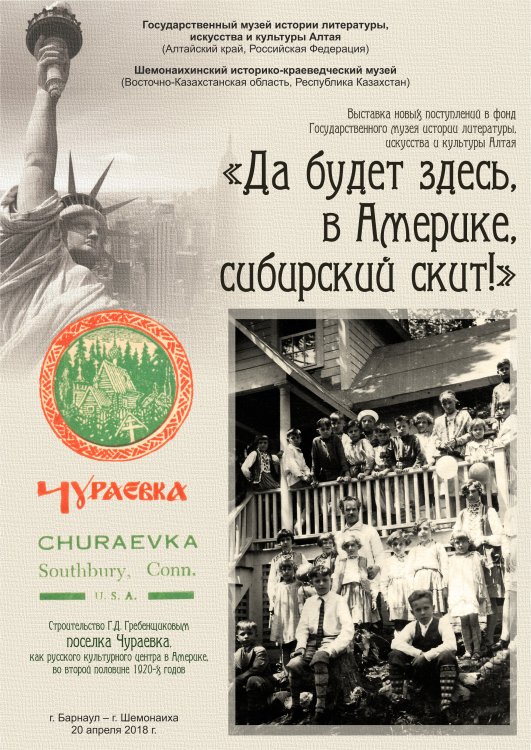

Georgy Dmitrievich Grebenschikov was a Russian writer, a descendant of an Altai nomad, born in Altai (the village of Kamenevka, now in the Republic of Kazakhstan), in the family of a collier. Having tried his hand in different professions from an early age, he entered the Tomsk University as a non-credit student. Supported by a prominent Siberian figure G. N. Potanin, he became a member of the Russian Geographic Society, traveled a lot and published many of his works. The writer rejected the revolution and left Russia for good. He spent his emigration years in Europe (1920-1924) and the USA (1924-1964). While in America, Grebenschikov founded a settlement Churaevka in Connecticut (thus he tried to realize his idea of culture building) and organized Atlas book publishing house. He was a prominent figure and spiritual leader among Russian émigrés. Grebenschikov was one of the initiators of the Pushkin Society in the USA.

In the literature of the USSR, Grebenschikov was invisible till 1990s: his name was banned because he cooperated with the Voice of America for some time while living abroad, and the collapse of the Soviet Union made way for the profit-making literature only. However, the name of Georgy Grebenschikov is very well known in Siberia, Altai region and... Kazakhstan (!). This is, no doubt, due to the fact that the author was born in Kazakhstan, lived there for a long time and even knew the Kazakh language well.

For example, the book Russian Pearls published in Kazakhstan in 2013 for Grebenschikov's anniversary collected essays on his friendship and encounters with Igor Sikorsky, Sergey Konyonkov, Fyodor Shalyapin, Nikolay Roerich, Ivan Bunin, and Nadezhda Levitskaya. Siberians were the first to discover his works via the literary and socio-political magazines Sibirskiye Ogni and Barnaul. The first collected works by Georgy Grebenschikov in Russia were published in 6 volumes in 2013.

Advertising posters on Grebenschikov exhibitions in Barnaul in 2013 and 2018. Photo from the State Museum of History of Altai Literature, Art and Culture (GMILIKA).

As Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva points out, “Georgy Grebenschikov’s phenomenon is that he knew the steppe, the steppe culture, and the tragedy of the steppe very well. His heart ached for the patriarchal culture, the Kazakhs’ culture in particular, which was destroyed not by the Bolsheviks but by the new way of life – the urban life style. In his novel The Churaevs he speaks about the fate of the Russian culture in relation to the urbanization process by showing a patriarchal Old Believers’ family. The novel raised issues such as preservation of religious faith, culture, and family-based life style. Would the foundations survive the current path of the country? Grebenschikov was a cosmist and believed that the revolution was just a grain of sand in the world’s history. He was able to look at his time from the perspective of greater history. This is, perhaps, the most powerful constant that society needs now.”

Besides, in his works, Grebenschikov could not help comparing his experience in Altai and Crimea. Whereas his book The Spring in the Desert was about his travels in Siberia, Kazakhstan and Mongolia, the writer kept The Crimean Journal, which he called his memoirs, while living in Crimea. Genre-wise, the book is a journal and essentially the writer’s creative laboratory.

Many pages in Grebenschikov’s Crimean journal are about the Romanovs. Grebenschikov visited the Livadia Palace in 1918 and then described every room in detail. A bit later, abroad, the writer met the Grand Duke Aleksandr Mikhailovich, sent him his book and received several replies to his letters.

In Crimea, Grebenschikov met such writers as I. Shmelyov, S. Yelpatievsky, K. Trenyov and Y. Chirkov, the artists I. Bilibin and N. Pinegin, and the public figure V. Vershinin. He described many of such encounters in smallest details. That is why The Crimean Journal, according to Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva, is of great interest to researchers.

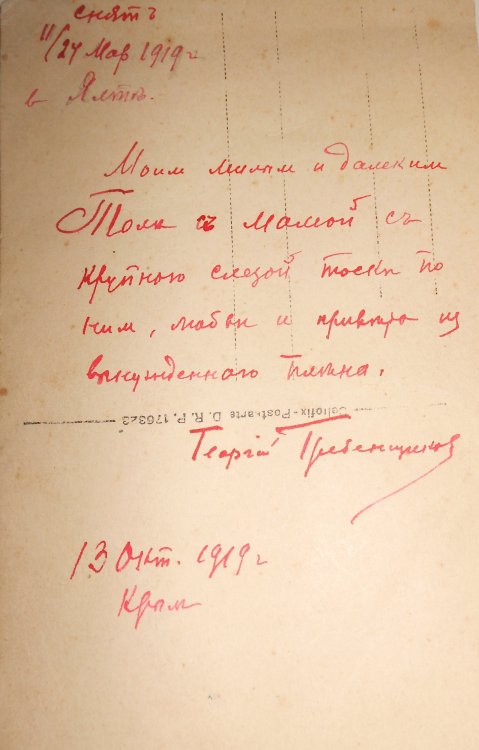

Thanks to cooperation of the Yalta Literature History Museum, Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva conducted a real literary research, looking for documents on the life of G. D. Grebenschikov in Yalta and the location of the writer’s house. She had to perform comparative analysis of pre-Revolution and modern city maps, and lists of households of the early 20th century. A curious fact is that while in Crimea, Grebenschikov used red ink in his correspondence and journals since there was no other color available. That’s the way he wrote a letter to I. A. Bunin. Grebenschikov also used the red ink to write on a photo he sent to his family.

The text on the back of a photo, written by Grebenschikov with the familiar red ink.

Most of Grigory Grebenschikov’s archive is in the State Museum of History of Altai Literature, Art and Culture (GMILIKA, Barnaul). The writer’s archive was brought to Russia thanks to the enormous effort of Renita Andreevna Grigorieva, a film director, a cultural figure, an actress, and a student of the great Soviet film director Sergey Gerasimov. She contributed to the discovery of literary names such as Vasily Shukshin, Valentin Rasputin, and Georgy Grebenschikov. “When the decision was made to republish Grebenschikov’s The Epic Ballade of Mikula Buyanovich, Rasputin was the one to compose the foreword. The writer pointed out that Grebenschikov wrote in big, intense strokes. Aleksandr Petrovich Kazarkin, Professor of Tomsk University, believes that Grebenschikov, Shishkov and Novosyolov were precursors of rural prose. They were the most impressive young regionalists,” said Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva.

Renita Andreevna Grigorieva and the writer’s great-nephew Aleksandr Shramko with Grebenschikov's book Yegorka’s Life published in Kazakhstan, illustrated with children's drawings.

Today, Crimean specialists would like to carry out a project similar to this one, but on the Soviet period, since the issue of the rehabilitation of Soviet literature became relevant. “While Soviet filmmaking and paintings have been rehabilitated, key Soviet texts are disappearing from literature curricular and textbooks. For instance, today’s children are not aware of books by Vladimir Lugovsky and Konstantin Paustovsky. We also consider writing a book on Paustovsky, Voznesensky and Vysotsky in Crimea.

In addition, the research on Russian literature in Crimea at the time of the Revolution and the Civil War should continue. Finding Grebenschikov’s photos of the Crimean period and his Voice of America audio records would be incredible. Grebenschikov always spoke of reconciliation between America and Russia. He believed that Russia and the USA were similar on account of their building spirit. According to Grebenschikov, there are lots of Russian people who consider themselves creators, but only a few “producers.” He was fond of the common cause theory of N. Fyodorov, and was fascinated by Vernadsky’s ideas on the noosphere, ideas of cosmism,” said Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva with a focus on future research.

Thus, getting to know the artistic world and works of Russian writers of the first Emigration Wave will help better understand the emotional experience of the tragic schism in the Russian history following the 1917 Revolution and the Civil War, and, most importantly, expand the list of names by adding those that were forgotten, and follow the development of the writers’ world view and their spiritual life. In their work, the poets and writers mentioned in the monograph tried to find the answers to this and other questions their contemporaries faced during that tragic era of troubles.

As Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva admitted, “Grebenschikov opened an enormous world of culture to me.” The modern readers would inevitably enrich their knowledge on Russia’s history and culture by discovering the novels by Grebenschikov and other émigrés writers.

*All images are provided by Svetlana Tsaregorodtseva