The annual celebration of International Women's Day was proposed at the Second International Conference of Socialists in Copenhagen in 1910. Klara Zetkin took the initiative and was supported by more than 100 women from 17 countries. However, the participants of the meeting did not specify an exact date. Since then, this day has been “wandering” in the calendar. In some cases, the holiday was celebrated on different days in the same country.

For example, in 1911, Germany chose March 19 as the celebration date, since the March Revolution in Prussia took place on this day in 1848. In 1912, Germany proposed to celebrate this day on May 12. The date of March 8 was selected not immediately, but only in 1975 at the UN General Assembly. This date was proclaimed a day to celebrate women's achievements in all fields.

Women's Day history

The tradition of the March 8 holiday started to gain momentum after women from Austria-Hungary, Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Russia, the USA, and other countries held solidarity rallies on this day in 1914. Some believe that the date was chosen in memory of the female workers' strikes in the USA, which took place on March 8 in 1857 and 1908. Interestingly, it is also connected with the events that occurred in the Russian Empire. In 1917, on this day (February 23 under the Julian Calendar), female weavers started a strike in Petrograd. It is believed that this strike marked the beginning of the February Revolution.

This holiday has its own colors: violet (purple), green, and white. They were proposed during the struggle of the British Women's Social and Political Union in 1908. Purple symbolized justice, green – hope, and white – purity.

During the long struggle for the rights and opportunities, slogans related to the right to vote and improving working conditions were most common. However, these events also influenced the perception of females in society, at work, in art, as well as in science and education.

Right to education

Universities were closed to women. In noble families, girls were taught at home, and their education often came down to learning languages, small talk skills, playing musical instruments, singing and dancing. Such examples as Maria Bolkonskaya from Tolstoy's novel were more common for book pages than real life. Women of lower classes were totally out of the question. Despite the fact that the Russian Empire was one of the first to establish junior schools for girls, this step did not enable them to get a full-fledged education that would allow the ladies to provide for themselves and their needs in the future.

In 1861, journalist and women's rights activist Julie-Victoire Daubie became the first student and – after graduation – a bachelor of the University of Lyon. This was a very important step on the way to higher education for women. For Julie herself, the journey to higher education was not easy: the girl from a poor family learned to read and write all by herself; with her brother's help she mastered Latin, Ancient Greek, German, Geography and History. Since the age of 20 she worked as a governess, was awarded with a teacher's diploma, but she was still far from higher education. In 1859, she wrote an essay “The Poor Woman in the 19th Century,” where she opined that poverty among women was associated with the lack of opportunities to get higher education. For this work, she was later awarded with the prize of the Academy of Sciences and Fine Letters in Lyon.

Female education emerged in the agenda of the struggle for women's rights in the 1860s. A university degree was equated with independence from male support, a chance to take control over one's life and find fulfillment as a professional. Until the 1880s, girls studied mainly in boarding schools at monasteries. However, Daubie decided to try her luck and take bachelor's degree exams. The Paris Academy refused her, but the University of Lyon allowed her to attend lectures on history and foreign literature. This was largely influenced by the Women's Newspaper petition, written back in the 30s. Daubie passed the exams, but Minister of Education Gustave Rouland refused to grant her the degree. Empress Eugenie, the wife of Napoleon III, personally stood up for the woman. In 1863, only two women received a bachelor's degree, in 1892 – 10; and in 1920, one thousand women mastered higher education.

Russian Empire

In the Russian Empire, major universities created Higher Female Courses, but diplomas were not issued to ladies. Rich girls went to Europe for education. It was the critic M. L. Mikhailov, who raised the issue of female education in the Russian Empire for the first time – in his article “Women, Their Upbringing and Importance in Family and Society.” It was published in Sobesednik in 1852. Dobrolyubov, Pisarev, Herzen, and Chernyshevsky continued to develop female equality ideas.

Leaving to get education, the girls sometimes had to enter into fictitious marriages. It was due to the fact that in the 19th century, women in the Russian Empire had no passports. They were registered in their father's or husband's document. A vivid example is Sofya Vasilyevna Kovalevskaya, the first female professor (even more so – a mathematician) in the Russian Empire. Her father refused to allow her to study abroad. So, she entered into a fictitious marriage with a young scientist Vladimir Kovalevsky and went to study in Konigsberg. She worked in the fields of potential theory, mathematical physics, and celestial mechanics. She found solutions for many classical problems that her predecessors failed to cope with. In 1889, she was awarded the grand prize of the Paris Academy for her research on the rotation of a heavy asymmetrical spinning top.

The women's movement in the Russian Empire was supported, first of all, by women from the upper and middle strata who could find time for charity, cultural, and educational work. Active actions started in parallel with the reforms of the 1860s, which were recognized as liberal. In 1858, female schools for all classes started to open. In 1863, higher educational institutions also opened their doors for ladies. They could attend lectures, but still could not enter the university officially. However, there were special courses with a curriculum equated to the university one. The most famous example is Bestuzhevsky Courses, established in 1878. Having passed such a course, a lady could teach or work in educational organizations.

There are female pioneers in various sciences: the first Russian female petrograph and paleontologist E. V. Solomko, theorist and educator M. N. Siryatskaya, zoologist Yu. I. Andrusova, chemist V. E. Bogdanovskaya, first female employee of the Pulkovskaya Observatory M. V. Zhilova. In 1872, Women's Higher Medical Courses were opened in St. Petersburg. N. P. Suslova became the first female doctor, and V. A. Kashevarova-Rudneva, who graduated from the Medical and Surgical Academy in 1868 by way of exception, became the first female doctor educated in Russia.

As time passed, women graduated from higher educational institutions and entered the domestic science with new ideas, views, and discoveries. Read more stories about the role of women in science and folk art in our series of articles for International Women's Day.

Read more on the topic:

A. N. Shabanova, An essay on the women's movement in Russia.

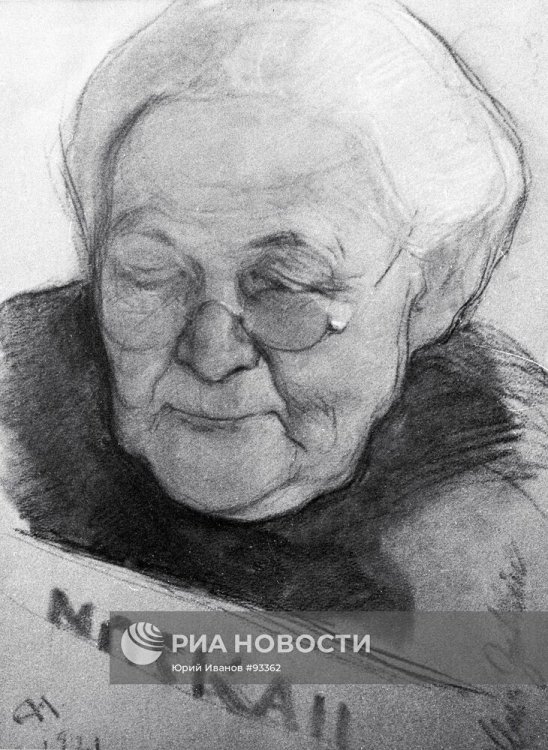

Фото на странице и на главной странице сайта: Юрий Иванов / РИА Новости