Tula scientists study the history of the Russian textbook and, more specifically, consider changes in the methods of teaching children to read and write.

The reading skill usually begins with an ABC book or a primer. A set of letters and sounds opens up an entertaining world of knowledge, where a literacy teaching manual becomes a reliable guide. However, at the same time, a primer is also a real historical document. It can be regarded as a phenomenon of book culture, a stage in the development of educational theory, a sample of illustrative design, and sometimes even as an ideological tool.

The first Russian textbooks – ABCs and primers – were designed to teach the younger generation literacy, as well as to provide for their spiritual and moral development. They enlightened people and formed their ideas about the world around them, about the society, and about themselves. Primer is a type of educational book that reflects the development of the national language and literature and obviously demonstrates the formation of pedagogical experience, in particular, the methodology of teaching native language and culture.

A complex research work of the scientists from the Tula State Lev Tolstoy Pedagogical University (Tula) is devoted to the history of the Russian educational book publishing. The specialists analyze the first textbooks and establish the relationship between the text and illustrative material; identify inherent didactic functions, methods of children's visual teaching, proposed by the authors of Russian educational literature of different historical periods.

Ekaterina Yuryevna Romashina – professor, Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences, dean of the Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities at the TSPUT (Tula) – told us about the first Russian ABCs and primers, the learning process principles, and the functions, in addition to educational, that were incorporated in the manuals for teaching literacy.

“A textbook is inherently different from any other book. Not only does it represent an informational model of a certain science, but it also becomes a methodological model that reflects the development level of pedagogy, psychology, and the methods of subject teaching at any given time. Textbook incorporates the ideas of theorists and practitioners on how to teach and study. In addition to the experience of human activity in a particular field of cognition and creativity, textbook also models the very educative process, i.e., a certain pedagogical experience. And this is exactly what makes a textbook.

The Medieval literature did not know the difference between scientific and educational literature. The school textbook evolution, its transformation from a book suitable for reading by schoolchildren into a sophisticated modern system, is the evolution of pedagogical experience, the evolution of pedagogical science, first of all.

However, there were very great technical limitations in the creation of an educational book for previous epochs. For example, the basic approaches to visual teaching were developed as early as the 17th century, but due to imperfect printing, it was very expensive to publish a primer with illustrations at that time, so such books did not have mass circulation.

Textbook is an ideal model of the educational process for both teacher and student. It contains and should embody: the general goals of education, as well as the specific goals and tasks of teaching a certain subject; didactically processed content of the basics of the humanity’s social experience in a certain sphere of activity; a certain organizational form of the learning process (class and lesson, individual, etc.); more or less explicit technology and methodology of teaching and learning.

Today these characteristics are embedded in a school textbook and can be “perceived” easily. However, the deeper we go back in time, the less pronounced these components will be: the pedagogical community had to collect and then accumulate the experience of didactics and private methods in a textbook,” Ekaterina Romashina noted the main specific features of a textbook.

“It is generally accepted that the first primers appeared in Germany during the Reformation. Why is this so? Because according to Martin Luther, the father of the Reformation, everyone should talk to God and read God's word not in Latin, but in their own language. That means everyone should learn to read. Luther created a little Bible, a primer for children. From this point on, the literacy manual begins to acquire a “methodological shell”: it receives a statement of course objectives (usually reflected in the preface); it emphasizes the selection and presentation of material in accordance with the child’s age; it offers students questions and tasks to reinforce their knowledge and skills,” the researcher emphasized.

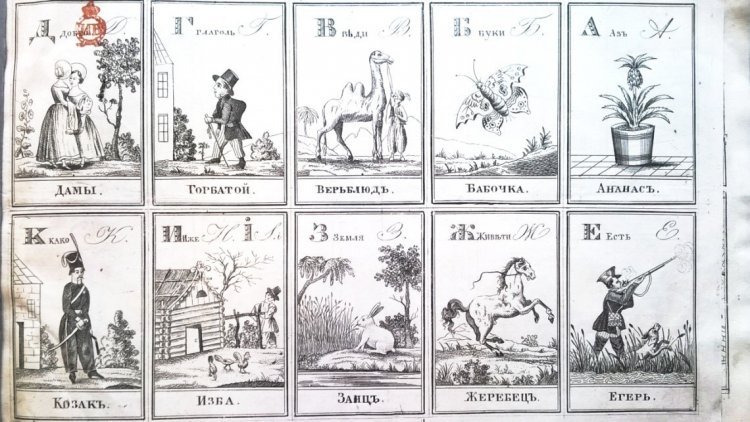

“A Precious Gift for Children: ABC in Pictures,” B.M., (1845. P.1). A sample of the 19th–century textbook, in which a letter is accompanied by the word(s) beginning with it and the corresponding image(s).

What textbook type is considered most effective for student learning?

“This is a complex and rather puzzling question. There is an inverse correlation here, however paradoxical it may seem. If a textbook is well-written and detailed, contains clear goals and objectives, didactically elaborated content, a specific methodology and form of teaching, then it is very convenient for a teacher, but, as a rule, it is short-lived – it will not be applicable in a changed situation. Conversely, a textbook with implicit model features may be in demand for decades. Thus, if a primer is composed according to the whole-word method, there is no other way to teach it. It is quite different when there is a problem of choosing a textbook. At the end of the 19th – beginning of the 20th centuries, Russia had dozens of types of elementary schools with different programs, from the middle of the 1860s to the beginning of the new century more than 2,500 textbook titles were published for them. It was not uncommon for the teachers of a district school to write and publish textbooks – and teach using them as they wanted. A teacher could use any textbook, even the one they wrote themselves, but they could not recommend or distribute it to other educational institutions without the approval of the Ministry of Education. By the beginning of the 20th century, about 28% of the Russian population was literate and a student in a public school was not expected to continue their studies. Therefore, a primer was very often the only textbook that a person would hold in their hands for their entire life.

I want to point out that the deeper we go back in time, the harder it is to talk about the effectiveness of a particular manual. We only see a textbook and can get a general idea of how that textbook was supposed to work. We do not know whether it was good or actually effective. What can tell us about it is mediated data: circulation, number of reprints, advertising catalogs, etc. As well as direct recordings: memoirs, letters, diary entries. However, these sources are not always reliable due to their subjectivity. For example, K.D. Ushinsky cited an excerpt from a letter by a village teacher with an enthusiastic review of his Rodnoe Slovo (Native Word) textbook. But he did not publish any critical remarks, yet there were some... Or Azbuka by Leo Tolstoy, the first edition of which received a lot of negative reviews and was very poorly sold on the book market. The writer reworked it radically, so that time the second edition was recognized by the pedagogical community and recommended by the Ministry of Education for use in public schools. Tolstoy created some outstanding texts for children, but he was not free from methodological errors,” Ekaterina Romashina noted.

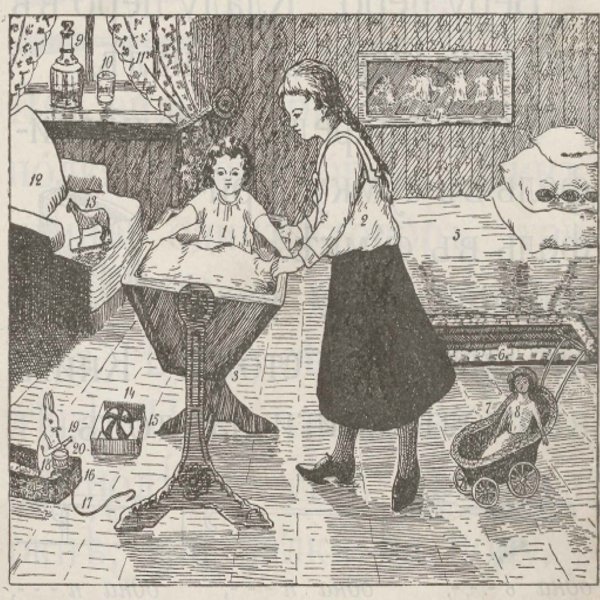

The Russian Empire was a multinational state and the Russian language was studied everywhere. As the scientist emphasizes, “There were textbooks for teaching Russian as a state language ‘for foreigners’. For example, teacher and school inspector M. A. Trostnikov developed a Russian textbook for the Baltic provinces, which was adapted to the phonetic structure of the language of Germans, Estonians, and Latvians. For example, Estonian belongs to the Finno-Ugric group of languages and the Estonians have difficulty pronouncing certain sounds of the Russian language. Trostnikov turned to the solution offered by Jan Amos Komenský in the middle of 17th century: the manual contained drawings with numbered objects and the corresponding words were numbered in the text. So, the child received visual support for memorizing the vocabulary of a foreign language.”

Trostnikov M. A. Russian speech. Yuryev, (1912. p. 24). An example of numbered pictures in language teaching.

The Christmas Tree: A Gift for Christmas primer by Anna Daragan, which was published in 1845 and later endured 15 re-editions, is noteworthy. The usual circulation of literature of that century was 1,200 copies, so we can talk about a certain popularity and demand for this manual.

“I think this is a very interesting and revealing example. Anna Mikhailovna Daragan is an extraordinary figure. Daughter of the rector of St. Petersburg University and later Senator M. A. Balugyansky, wife of the Governor General of Tula Region, mother of five children, she was well known in court and had experience of writing pedagogical works,” Ekaterina Romashina noted.

Art. Heinrich Pillati. Daragan A. M. Christmas Tree: A Gift for Christmas, St. Petersburg, 1874.

How did this primer prove its relevance and effectiveness in teaching students to read?

“This handbook was published in a printing house that de facto belonged to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and had great printing capabilities. The primer has excellent quality illustrations. Anna Daragan used the sound method of teaching literacy 20 years earlier than it became widely used in Russia. Apparently, she was familiar with European educational practices and used them for home schooling.

In Daragan's textbook, the text and picture were connected directly for the first time in the domestic practice of book publishing: Azbuka contained the following tasks for a child: ‘Have a look at the picture and tell me what you see’. At least, I am not familiar with any earlier case of such a methodological technique,” Ekaterina Romashina expressed her opinion.

Daragan A. M. Christmas Tree. A Gift for Christmas. St. Petersburg. 1845. P. 80.

Were any national motifs used in the first Russian ABCs?

“Up until the end of the 19th century, ABCs in Russia, as well as throughout the world, were mainly oriented toward village life. Why? Not only because the village population prevailed over the urban population, but also because the educators perceived the child as a pure ‘natural’ creature, who was better off living away from the dusty and stuffy city and the secular society influence. The 19th-century Russia was a rural country, with its kokoshniki, sarafans, wooden huts, and Central Russian landscapes. So, the primer has all these things, too. However, in a textbook made for noble families (for example, Daragan's Azbuka) the countryside landscape and sarafans could be combined with European clothes and household things,” the researcher states.

Art. A. Agin, engraver E. Bernardsky. Daragan A. M. Christmas Tree: A Gift for Christmas. St. Petersburg, 1846. PART 2. P. 106.

Professor Ekaterina Romashina and her colleagues from the Institute for Strategy of Education Development of the Russian Academy of Education, the Higher School of Economics, the Russian State University for the Humanities, and other universities currently participate in a project for the RFBR grant titled “Urban Discourse in Russian School Textbooks of the 20th Century: Rhetoric, Aesthetics, Didactics” (Project #20-013-00246, supervised by Doctor of Pedagogy, Y. G. Kurovskaya) and study the image of the city, its functions and role in the ABC books, primers, and books for reading.

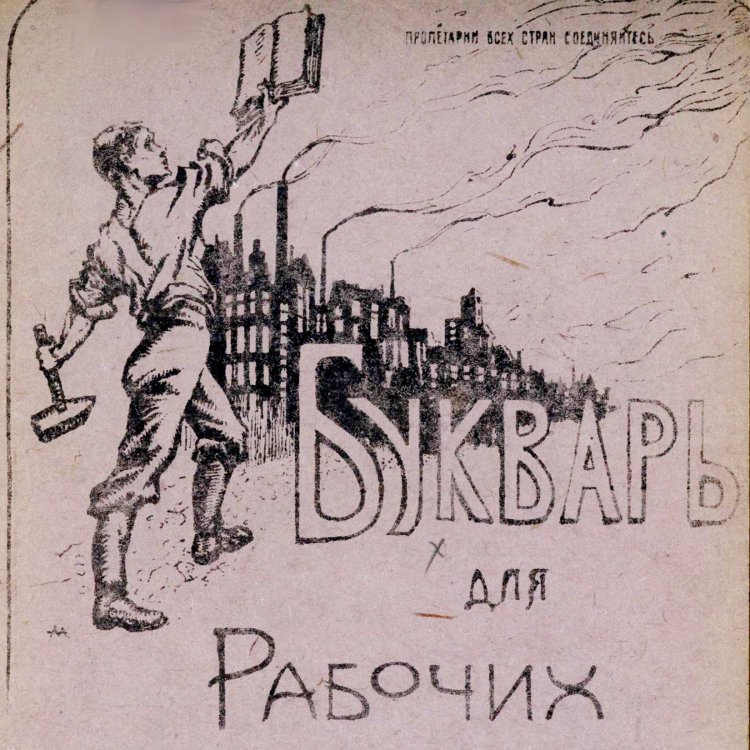

Ekaterina Romashina pointed out that “primer has always been an ‘ideologically loaded’ book – at all times and not only in our country. Why? It is the first (and previously often the only) book in a person's life; it is supposed to acquaint them with the basic values of society and the state. This is especially evident at the turn of ages. For example, in the early years of the Soviet regime, primers were created for children and for adults – everyone between 8 to 50 years old had to be literate. Including political literacy – the new ideology had to be spread everywhere. But the material presentation was different. The child, unburdened by the ‘dark past’, is the builder of a bright future, the main actor of social transformation; the most common words in such a textbook were ‘on one’s own’ and ‘themselves’. The adult was ‘re-educated’ by incorporating the new ideology into familiar practices of life. First of all, through a person's professional background. Primer for Railroad Workers, Primer for Forest Workers, Primer for Collective Farmer, Red Army Soldier's ABC Book, etc. were created. The first words and then texts were about steam locomotives, the Prodnalog, the struggle against the Entente, etc.”

Primer for Workers. Pg. 1917. The title page.

Blecher F. N. The First Book for Teaching Literacy in Kindergarten and Preparatory Class. – M.: Educational-Pedagogical Publishing House, 1935.

The History of Textbook Portal (http://primer.tsput.ru/), which contains digital copies of textbooks and scholarly publications about the history of textbooks from different countries and eras, was created under the guidance of Ekaterina Romashina on the TSPUT website. It is based on the collection of Russian educator and scholar Vitaly Grigorievich Bezrogov. The documents’ electronic versions are available for free access and will be useful both to those who are professionally engaged in the history of textbooks and to all those who are interested in the Russian science of primers.

The history of domestic educational book publishing has shown its interconnection and interaction with the processes of literacy, formation of the foundations of pedagogical education, methods of teaching subjects, as well as with the cultural and historical situation in the country as a whole. Referring to the possibilities of development and education of children, a teacher or a tutor put the learning process in perspective and searched for the best ways and techniques of presentation and mastering of the material, providing for the student’s personal growth.

All images are provided by E. Romashina

Article autor Ekaterina Romashina

“FUN AND USE FOR CHILDREN”: PICTORIAL ABCS IN THE RUSSIAN EDUCATIONAL BOOK PUBLISHING OF THE 19T....