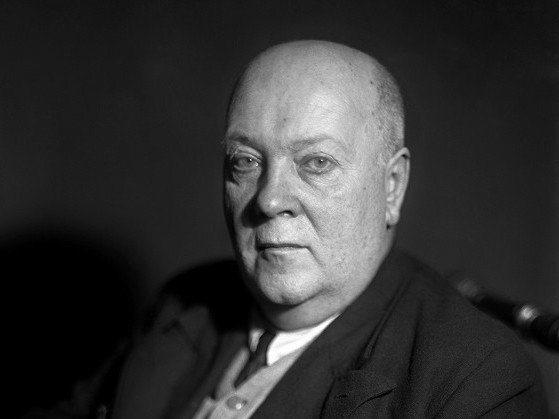

Official:

Alexander Evgenievich Fersman. October 27 (November 8) 1883 – May 20, 1945. Russian and Soviet mineralogist, crystallographer and geochemist. Vice president of the USSR Academy of Sciences. Winner of the Lenin Prize for his scientific works, the First-Degree Stalin Prize. The poet of stone.

Life and Work:

1. “Almost half a century of life full of search and devotion, almost half a century of love, sturdy and straight, infinite love for stone, the lifeless stone of nature, to a piece of plain quartz, to a block of iron ore’ – this is what Alexander Fersman wrote in his scientific and lyrical novellas titled Memoires of Stone. It is not by chance that Alexey Tolstoy, the contemporary of the scientist, called him the “poet of the stone.”

2. A. Fersman was a student of Vernadsky and a mineralogist. He discovered apatite and nickel ores in the Kola Peninsula and native sulfur deposits in Kara Kum. He is more familiar to the general public as an author of the book Engaging Mineralogy. He popularized his science, was vice president of the Academy of Sciences and head of the Mineralogy Museum of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

3. Fersman began collecting stones since a very tender age. Even though he was a grandson and a name-sake of Russian artillery scientist Alexander Fersman and a son of military architect Evgeny Fersman, he was not interested in military sciences. As a boy, he spent each summer in the Crimea, at the estate of Alexander Kessler, his mother’s brother and a chemist. The uncle told interesting stories about each stone they found and thus he got his little nephew engaged in mineralogy.

4. In Greece, where Evgeny Fersman was appointed a military attaché, the interest in stones only grew. While traveling around Europe, the future geochemist and mineralogist collected stones and spent enormous amounts of time in natural science museums. His parents supported his interest in sciences and developed him in all possible ways.

5. Wandering around the world taught Fersman to quickly accommodate to harsh conditions: later in his adult life the scientist amazed his colleagues by easily adjusting to any inconvenience and never losing his spirit. “He could use anything as a means of transport, he could sleep in any surroundings and eat very little plain food. On the way he told us about his childhood, about his career, presented his scientific views to us concurrently making a host of minute domestic comments,” wrote Dmitry Scherbakov, a student of Fersman.

6. Sasha Fersman graduated from high school in Odessa where his father had been appointed director of a Cadet Corps. At the request of his father, Alexander gave cadets classes in mineralogy and geology. He would be engaged in popularizing his science throughout his life.

7. When Evgeny Fersman was transferred to Moscow to head Alexander Military School, his son also left Odessa University for Moscow University. It was here that he became a student of great professor Vernadsky. “We spent no less than 12 hours a day in the lab, sometimes even staying for the night as the analyses lasted 24 hours; we read reports twice a week at the club headed by Vernadsky, we classified the pieces of his collection and listened to his enthralling lectures,” Fersman recalled later. In his own words, the main lesson he learned at that period of time was that the ability to work was the most important skill in life.

8. Geochemistry as a science did not exist back then. It was Vernadsky and his students who were laying its foundations there and then. “The word ‘geochemistry’ had not yet been uttered, but we were becoming geochemists pondering and going deep into eternal laws of the chemical transformation of the Earth,” Alexander Fersman wrote later.

9. In 1907, Fersman graduated from the Department of Natural Sciences of the Physics and Mathematics faculty of Emperor’s Moscow University with the major in “geology, paleontology and mineralogy.” Upon the recommendation by professor Vernadsky, Alexander remained at the chair of mineralogy to prepare to obtaining professorship.

10. The same year Fersman went abroad to perfect his skills and gain new knowledge in scientific laboratories in Germany, France and Italy. Upon returning from a 2-year trip he began working at Moscow University, however, at the end of 1911 he and many of his colleagues left the university as a sign of protest against the reactionary policy of the Ministry of Education. Professor Fersman began to give lectures at Shanyavsky Public University where he gave a course on mineralogy and the first-in-the-world course on geochemistry.

11. It was during his scholarship at Heidelberg University in Germany when Fersman started to research natural diamonds. It was not surprising that after the revolution Fersman was invited to conduct the overhaul of the Diamond Fund and to study the famous Shah and Orlov diamonds.

12. In 1919, Fersman became one of the youngest of full members of the Russian Academy of Sciences at that time. In 1927-1929 the scientist was elected vice president of the Academy.

13. For Fersman the main points on the geological and mineralogical map were the Kola Peninsula and Central Asia. In Khibiny the expedition led by Fersman discovered the deposit of apatite, and in Monchetundra they discovered the deposits of copper and nickel. Fersman established the Tietta high-level station that later developed into the Kola Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences, nowadays the Kola Scientific Centre of RAS. In Central Asia Fersman discovered deposits of sulfur and uranium ore.

14. In the 1930s, the scientist established and headed the Urals Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Crystallography named after M.V. Lomonosov. Neither field trips nor administrative duties prevented him from writing Geochemistry, a magnum opus in 4 volumes.

15. During the World War II Fersman created and headed the commission for scientific support of the Soviet Army at the Branch of Geological and Geographical Sciences of the USSR Academy of Sciences. In his book War and Strategic Resources published in 1941, the scientist appealed to geologists: “In the decisive battle we need to raise the very depths of the Earth against the enemy! Let the heaps of metals, concrete, and explosives grow into the seventh wave whose power will crush the Nazi avalanche.”

16. In 1943, Fersman published another book titled “Geology and War.” Back then he headed the Institute of Geological Sciences of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

17. Fersman lived up to the glory of the Great Victory, however, the scientist died the same May as the years of harsh field trips and intense work with “brain and hammer” (as the old geologist motto says) affected his health.

18. “You see the chaos and mess – Greek, Arabic, Hindu, Persian, Latin, Slavic origins, gods, goddesses, stars, planets, cities, countries, last names, often without any order or thorough consideration,” this is the excellent and vivid description Fersman gave to the Mendeleev’s Periodic Table. The scientist called the Moscow Subway a mineralogy museum featuring excellent specimen of marble, granite, and limestones.

19. Now the Mineralogy Museum at the RAS is named after Fersman who had headed it for many years. It is one of the most famous mineralogy museums in the world and one of the largest in Russia. There are two minerals named after the great scientist: one is fersmanit discovered in the Khibiny and the other is fersmit from the South Urals.