Researchers of the South Ural State University (SUSU), Chelyabinsk, and the Institute of History and Archeology of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (UB RAS), Yekaterinburg, study the Bronze Age and the early Iron Age, and, in particular, ancient settlements and burial grounds in Southern Urals and Western Siberia. The types of artifacts and burial grounds support the hypothesis that there various peoples migrated en masse via this Eurasian zone. Archeological sites demonstrate that ancient humans were highly mobile, and help us obtain new knowledge about the origin of peoples.

The Bronze Age was a long and important period in the history of humanity, which initiated interactions among people with different cultural traditions. That was a time when all social systems were restructured and life support systems changed. Rapid development of metallurgy was characteristic of the Southern Urals of that period, with the new field becoming a part of a cluster of innovations, including discoveries in mining and technology. Sedentary animal husbandry became a unifying factor in the models of living of indigenous peoples and new arrivals in the region. People’s movement to new territories promoted cultural exchange processes. The Bronze Age Ural architectural objects found by the researches were part of a technical and economic revolution.

Specialists of the South Ural State University (Chelyabinsk) conduct long-term archaeological and paleogenetic research in trans-Ural steppes. Excavations of ancient encampments and burial grounds, and analysis of ceramics, weapons and labor tools found do not just allow dating them to the bronze era. For example, the scientists found parts of spoke wheels buried in the ground, which proved the existence of wheeled vehicles at the time and thus confirmed that people developed wheeled transport and used draught-horses during that period. The findings from the burial sites, with a whole range of attributes of war, speak of the process of opening new lands and of self-defense practices. However, the Bronze epoch in South Urals, in addition to being the embodiment of war, also became the time of peaceful interactions among Indo-European and Finno-Ugric peoples. Human bone remains and artifacts confirm those interactions and mutual enrichment.

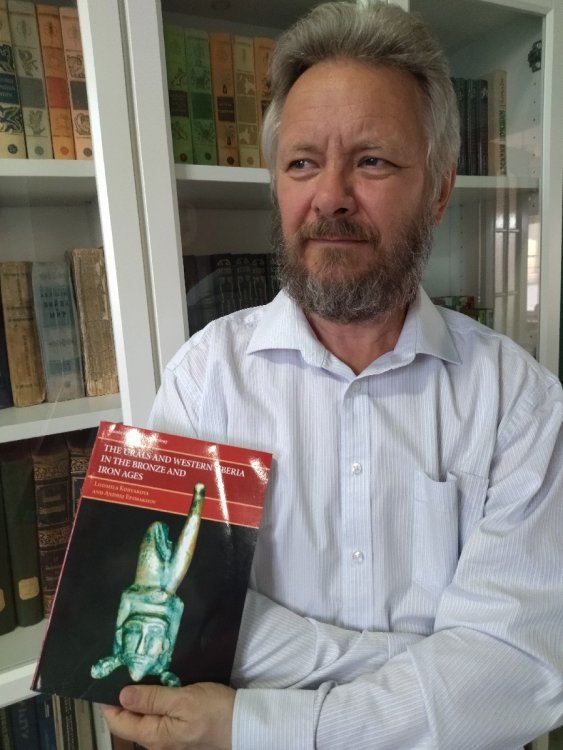

Andrey Vladimirovich Epimakhov – Doctor of History, Leading Research Officer at the Institute of History and Archeology of the UB RAS (Yekaterinburg), Professor of the Subdepartment for Russian and Foreign History of the South Ural State University (Chelyabinsk) – presented a monograph written for foreign readers where the authors present a consistent picture of the history of the ancient population of Southern Urals and Western Siberia in the Bronze and Iron Ages, and told us about the specifics of that period in that part of Eurasia and, in particular, about archaeological findings related to settlements and burials that are evidence of Eurasia’s dynamic and independent development.

On April 21-22, 2021, within Days of Historical Science at the South Ural State University (Chelyabinsk), Andrey Epimakhov made a presentation of the book GATES OF EURASIA: THE URALS AND WESTERN SIBERIA IN THE BRONZE AND IRON AGES, published by Cambridge University Press and republished in China. The monograph was co-authored by Lyudmila Nikolaevna Koryakova, Doctor of History, Chief Research Officer of the Institute of History and Archeology of UB RAS (Yekaterinburg). Andrey Epimakhov used to be her post-graduate student, and has worked with her for many years since.

As Andrey Epimakhov remarked, “back when I was working on my Candidate thesis, there came the idea of doing a panoramic study for the foreign reader since the interest to the topic was growing and important discoveries were made in the 80s and 90s. The idea of what we wanted to do had formed by the late 90s. Professor Koryakova specialized in the Early Iron Age at the time. But since I was working on the Bronze Age, she immersed herself in that topic as well. It became clear that both eras together would illustrate the area much better and help follow the social trends we were interested in. As a result, Lyudmila Koryakova has been researching the Bronze Age for many years.”

The first edition of the book THE URALS AND WESTERN SIBERIA IN THE BRONZE AND IRON AGES by LUDMILA KORYAKOVA, ANDREJ VLADIMIROVICH EPIMAKHOV came out in 2007. The authors had worked on the monograph for years before they fully structured and adapted it for a prepared reader, given the specific nature of the terminology and Russian toponymics. The foreword was written by Philip Kohl, an American scientist specializing in Eurasian archeology and the Caucasus region in particular. Similar to Russian historians, he is engaged in social archeology and interested in complex societies.

The scientist holding the 1st edition of the monograph in English, publisher: Cambridge University Press. 2007.

Moreover, the book by Lyudmila Koryakova and Andrey Epimakhov could be useful to scientists in related disciplines. As the researcher clarified, “archeology does not shy from communication with all specialists: we always need more confidence in our conclusions and look for outside support, e.g. in geology or biology. Methods of paleogenetics have become most common. Complexities of our cultures are not easy to understand for a specialist in another field. However, matching various data to historical processes creates the general picture. For instance, during fieldwork, we sometimes wish we had particular specialists (anthropologists, soil scientists, etc.). It should be clear that archaeological findings fail to provide final answers to many questions. There is enormous room for cooperation.”

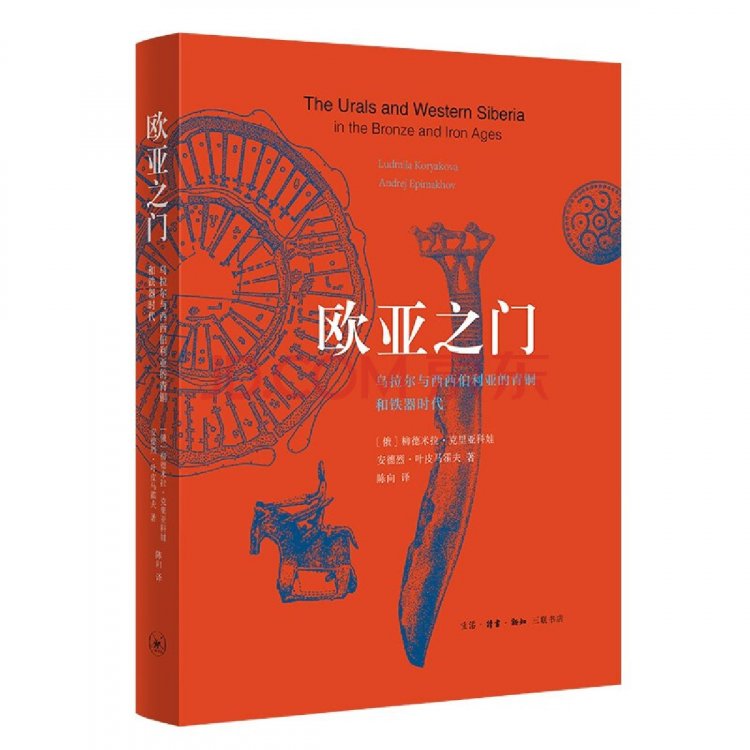

As Andrey Epimakhov emphasized, “the book was received quite warmly, with several reviews published in good magazines, and went out into the world. It was purchased by libraries and then by colleagues. It is being read and cited. Apparently, there hadn’t been a single overview work on this major region in a language accessible to most readers. The book was written specifically for foreign readers, explaining some things. Therefore it could not be simply translated into Russian. The 2nd edition came out in 2014. Later, Cambridge University Press suggested republishing the book in Chinese. And in 2021, it came out in China with a slightly different title: GATES OF EURASIA: THE URALS AND WESTERN SIBERIA IN THE BRONZE AND IRON AGES.

According to Epimakhov, the work presented by the Russian scientists is “a social history of the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, showing how the world changed, what external and internal factors were in play, and how it reflected on archeology.”

Lyudmila Koryakova, Andrey Epimakhov. GATES OF EURASIA: THE URALS AND WESTERN SIBERIA IN THE BRONZE AND IRON AGES – a monograph, published in Chinese in 2021.

In what way could the Bronze Age in South Urals and Western Siberia be interesting to archaeologists/historians research-wise?

“This is a key epoch. A non-stop time. The first elements of the global system emerged in that era: the first states, the first land-based transport, the first transformations of one material into another – what we now call metallurgy. It was a quantum leap in human history. Southern Urals may look peripheral in this regard. Nonetheless, it was the time of open and interconnected spaces, the time of gigantic migration. Anthropologists and archaeologists believed that the Indo-European migration across the entire steppe zone had reached North West China. This hypothesis has been confirmed genetically. Southern Urals were not just a flag station on that route. This region has its own history and development, as we know already from a series of settlements similar to Arkaim. That is, a rather remarkable phenomenon developed in the periphery. But we have a methodological dissonance here. The convention is that “light comes from the East.” But facts speak to the contrary: many innovations emerge in the periphery. So Southern Urals and Western Siberia demonstrate their own development patterns; they had their own, booming life. We cannot see this life in its process as all we have is archaeological sites. Imprints of the time. At the Early Iron Age, this was also a zone within a huge world of the Scytho-Siberian nomads, as evidenced by burial sites,” the scientist explained.

Clearing a burial site. Bronze Age burial site at Komsomolsky (Chelyabinsk Region).

What are the current trends regarding assessment of the Bronze Age in Southern Urals? Which one do you support?

“As for the local Bronze Age, most specialists do not believe that it was a period of globalization. My assumption is that major systems of this kind cannot emerge rapidly. There has to be a prehistory, one that originated in the Bronze Age.

There were stateless societies, but with huge territories with similar culture, extending million square kilometers. Zones with similar metallurgical traditions for example. How does such a cultural commonality develop and how is it maintained? I believe there were communication mechanisms created to reflect the social complexity, the international nature of the elites or scarcity of resources spread unevenly in the Eurasian space.

There are more concrete issues that have been discussed for decades, e.g. the discovery of a wheeled vehicle by archaeologists. There comes the endless discussion: where was it invented? I support the idea that, technologically, the wheeled vehicle technology and the driving skills first developed in the Eurasian steppe. Then, East Asian states picked this invention up with incredible speed, and the innovative technology became a brilliant article of war. There is a lot of such contentious issues, which cannot be resolved by focusing on South Urals alone since they lead to the Eurasian space,” the researcher believes.

Are there practical difficulties with finding things from that area?

“Normally, excavations follow a period of exploration. Bronze Age sites are very large: they can be seen on snapshots from the space and aerial photos that have been taken by the government since the 1940s. To obtain quality information, we work on sites that were found previously. For Lyudmila Koryakova and me, the Kamenny Ambar site, which includes a settlement and burial grounds, became such a place for many years. The findings have been included in all major works on archeology and paleogenetics. There were well preserved, which helped. We have the largest series of paleogenetic materials for these areas. This creates a more detailed picture, with different questions asked. Let me give you an example: a burial site was found with the remains of 8 children. How and why did they end up in one grave? The scientists were able to perform genetic analysis on 5 of them and found that three of them were brothers. There may have been a tragedy: a winter famine or disease. By the way, materials on South Urals confirm that there were plague and hepatitis in Eurasia as early as 4,000 years ago. Now, we can think of the role the diseases in the life of an ancient person and the history of groups. In our area, we focused on one site: its architecture, climate, economy, etc. Combining information on settlements and burial sites brings new understanding,” Andrey Epimakhov said.

Bronze Age artifacts. Left – pottery. Right – a jewelry-casting mold. Photo. Photos by A. Tairov and A. Bersenev

Stone caps for maces from a grave at Kamenny Ambar-5 burial site (Bronze Age).

Bronze spearhead. Kamenny Ambar-5 burial site (Bronze Age).

What is the fundamental difference of Bronze Age findings in South Urals from those from the Iron Age?

“The Bronze Age is the start of animal husbandry, which is associated with settled lifestyle. There were settlements: people lived in one place, dug wells, smelted metal. The Iron Age only left burial sites in the steppe zone, with weapons and nomads’ ritual items, but those were only part of life, of course. In the Iron Age, there were major differences between the forest-steppe zone and the forest zone: there is a hillfort, settlements, burial grounds,” Andrey Epimakhov described.

To interpret the data collected in the trans-Ural steppe (in Chelyabinsk and partly in Orenburg Region), Ural scientists apply various methodologies, depending on the objectives of their research.

“My objective is to build a general picture without losing the individual features. For example, we found tiny pottery on a number of occasions. It turned out to be children’s toys, which is a very rare thing to find,” emphasized the Ural scientist.

A miniature vessel from a Bronze Age burial site.

The current project led by Andrey Epimakhov: Migration of Human Groups and Individual Mobility through Multidisciplinary Analysis of Archeological Information (the Bronze Age of South Urals) (2020-2022), supported by a Russian Science Foundation (RSF) grant, is aimed to measure the degree of mobility of ancient people, using methodologies of geochemistry. Based on stable isotopes of strontium, specialists are reconstructing traces of the origins of humans and animals, comparing various life support patterns and degrees of consolidation of Bronze Age settlements. The difference in the composition of the isotopes shows if the individuals were indigenous or alien and where the latter originated from. Then the scientists make maps and follow the movement of the region's population in order to build the general historical picture in the end.

Are there any “blank spots” left in the research of South Urals of the Bronze and Iron Ages?

“There is always something, of course. For instance, the origin of this series of fortified settlements of the Bronze Age. The population, obviously, came from elsewhere, but the question is where they came from, if there was a starting point or the culture developed here, and that still makes scientists rake their brains. There is a lot of related questions as well: no war injuries, but there is a wheeled vehicle and a lot of weaponry. I think that the migrants came here, expecting an attack. But they found no real enemies. That is why the practices of fortified settlements and burying the dead with weapons were gradually going out of use. My hypothesis: this was a frontier that did not last long as such,” the researcher commented.

A fragment of a defense system during excavation. Kamenny Ambar settlement (Bronze Age).

A children’s grave with arrowheads (Bronze Age)

The main goal of Andrey Epimakhov’s current work is linked to chronology. According to the scientist, “without a chronological system, we find ourselves in an odd situation: not knowing causes from effects. For the Kamenny Ambar complex, for example, we are trying to use statistical modeling to build the chronology of the burial site. We do not know how long the burial site was used for, while we would like to understand what kind of a group was behind it and how many people lived in the settlement. Chronological comparison will tell us how many people died every year approximately, and then we will be able to compare that to the size of the settlement and estimate the total number of people who lived there. In this case, size matters for history. Well-based demographic estimates allow building economic and social models. By adding details to the picture, we delve into history.”

Thus, the archaeological legacy of Southern Urals and Western Siberia reveals processes and key events in the history of the Eurasian space during the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age. Having become a unique place of ethnocultural and ethnopolical transformations, the region reflects migration routes and the close historical links between ancient peoples.

All photos and pictures are provided by Andrey Epimakhov