The studies of scientists from the Institute of Language, Literature and History at Komi Research Center of Ural Subdivision of RAS are aimed at unimpaired functioning of the Komi language, which is a state language in the republic along with the Russian one. Promoting the language, culture and literature of Komi ethnos opens the specifics of national mentality and fundamentals of spiritual and cultural traditions for small-numbered peoples (native minorities) of Russia. The relevance of language system comprehensive study is to assist to promoting the culture of oral and written speech among native speakers of the Komi language and will enrich the general theory of Perm regional culture.

Komi and Udmurt peoples form the Perm branch of Finn-Ugric language family. Perm peoples have always lived within the boundaries of their national state entities as a rule: the Udmurt people lived in the Republic of Udmurtia, Komi-Syryenian people – in the Republic of Komi, while Komi-Permyak people – in Komi-Permyak Autonomous District. In early past century, independent literary languages developed on the basis of local dialects – Komi- Syryenian, Komi-Permyak and Udmurt ones.

In particular, Komi-Syryenian or the Komi language (which in 2018 marked 100th anniversary of creating regulatory framework for the present literary language) is unique, as it can boast of linguistic means that have no one-to-one correspondence in other languages. The Komi language acts as the one of cross-cultural communication: it is spoken by scientists from Hungary, Finland and Estonia (these languages belong to the same family). Acquiring the status of state language by it in the Republic of Komi allows for not only reviving the national traditions, but introduce the language, and therefore the traditions, customs and spiritual culture of native people to Russia-speaking population of the region.

There are areas in current Finno-Ugric linguistics which still demand special attention or have yet failed to be completely studied by the specialists. For instance, these include the influence of Russian language on grammar and syntax of Komi one, functional and communicative aspects of various language units, dialectic aspects of the language, in-depth study of regional lexical material, vowel system, etc.

The years-long research work of the scientists from the Institute of Language, Literature and History at Komi Research Center of Ural Subdivision of RAS (the city of Syktyvkar) is the evidence proving the comprehensive and in-depth study of languages and culture of Finno-Ugric peoples. For instance, the methods of production, morphology, semantics and analysis of grammar categories show unique features of the Komi language and the obtained theoretical results, as a consequence, provide an opportunity for interaction with adjacent language disciplines (Finno-Ugric syntax, semantics and history of languages). Lexicological research carried out by the scholars introduces the history of Komi ethno-cultural areas. The results of linguistic work produce direct practical output for the development of new Komi language teaching methods for national schools and therefore have been recommended as normative grammar textbooks and learning aids for those who would like to learn the Komi language or improve the speech and communicative skills. The linguistic and national geographic nature of the text books helps solidify knowledge better.

Linguist, head of language, literature and folklore department at the Institute of Language, Literature and History at Komi Research Center of Ural Subdivision of RAS Yevgeny Tsypanov explained what makes the Komi language and special aspects of its language system (grammar and lexicon in particular) singular, as well as highlighted the pressing problems of promoting and popularizing the Komi language in contemporary society.

The history of Finno-Ugric academic school of Komi linguistics can be traced back into 20th century. “The traditions of learning the Komi language at the Komi Research Center were established long before the Academy of Science founded its branch in the city of Syktyvkar, which happened during World War Two. Actually, this tradition was set up back in 1920s by first Komi linguists V. A. Molodtsov, V. I. Lytkin, and A. S. Sidorov. Before the Institute of Language, Literature and History (ILLH) was founded in 1970, a department of historical and philological research comprising a special group of linguists had been functioning at the Komi branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences,” Yevgeny Tsypanov reminded.

Today, ILLH is one of the largest centers of Russian and international Finno-Ugric studies and Northern ones, as well as continues to develop the traditional areas of academic school.

According to Tsypanov, “the language sector of ILLH currently employs 14 people, the Syktyvkar State University has two positions of the Komi language teacher, and two more specialists work at the Education Development Institute. The linguists work on the basis of traditional language description principles. The most thoroughly studied areas include dialects, grammar and lexicon of the language. The most substantial gains were achieved on the cusp of centuries and in 2000s: we published great standard bilingual dictionaries, academic grammar (morphology) book Encyclopedia. Komi Language (M.,1998), the first one in the Komi language, was issued, thematic monographs and industrial languages came out.”

This year, linguist Yevgeny Tsipanov marked his 35th birthday. As for the task of language preservation, the scientist accomplishes it by way of publishing the Komi language dictionaries, translating books, studying literature texts, folklore materials and various dialectic sources, participating in different educative and scientific projects.

What are the specific features of the Komi language? What makes it singular?

“The singularity of it takes its cue from the specific features of ancient Finno-Ugric proto-language and the results of later language changes: these are the absence of grammatical gender, availability of many cases, verb tense forms and adverbial participle categories, possessive suffixation, etc. There are few studies and research papers in the field of linguistic world view, but the materials of dictionaries offer many interesting facts. Standard grammars provide the insight into literature Komi language based on central Syktyvkar dialect, which has taken in the specific features of many other dialects. As far as the lexicon is concerned, the literary language has long been enriched at the expense of all dialects and subdialects. An important role in it belongs to Komi writers, natives of different local villages,” the scientist stressed.

What impact do the conditions of current language situation (bilingualism) make on variability of phonetic, morphological and lexical systems of Komi language? What about the role of contacts with sister languages and Russian one?

“All language systems have initially been variable in dialectic continuum including ten Komi-Syryenian dialects. Naturally, the bilingualism of Komi language adds more of variability, especially in lexicon. It is no secret that Komi have long been using Russian words along with or even instead of native ones – for instance крыша (roof) instead of вевт, аренда (rent, lease) instead of кöртым, etc. Variability is added in morphology as well. The same is true for verb корсьны (to look for, search) – along with traditional native words, Komi use the ones in locative case like in Russia language: корсьны вöрысь and вöрын (вöр means forest). Today, there are no active contacts with other Finno-Ugric languages, and the Komi language is active in contacting with Russian one alone,” Tsypanov explained.

How does Komi language develop today, and how is the generation of language innovations manifested?

“In the conditions of the current linguistic situation, only literary Komi language is active in developing. It has a strong impact on dialects as well via the Internet and media. At present, the representatives of young and mean-age generations of Komi people speak mixed literary-dialect languages. The hotbeds of language innovations generation take their cue from the active Komi-Russian bilingualism which leads to the loss of former specific features of Komi language. For instance, the Komi-speaking media have stopped using the forms of unobvious second past tense and analytical past tense. Only one past tense form is used like in the Russian language,” the scientist commented.

What are the key problems as to the establishment of modern lexicon and spelling of the Komi language?

“There are spelling problems, but they are not solved, as the writers, journalists and many teachers do not want any changes in spelling. Moreover, the language discipline has broken down over the past decade, and even such magazines as Войвыв кодзув and Арт print materials with random spelling and mixed-dialect texts in author’s version,” Tsypanov believes.

Starting from 1980s, a trend of forming new words and word combinations both instead of existing borrowings and for designation of new realities coming into modern public practice has been traced in the Komi language.

How are neologisms formed and what types of them can be identified?

“Over the past 30 years, active enough purization of Komi- Syryenian literary language lexicon has been taking place. The total number of neologisms of originally language origin amounts to 2,100 ones. Naturally, a lot of new words are borrowed from or through the Russian language. We are interested in the first group of words, which can be divided into several groups by methods of formation and sources of neologisms:

1) pure neologisms formed artificially – айлов (man), изсир (amber), йидi (iceberg), оланпас (law), сюраныр (rhinoceros), кывпель (syllable), тювгач (rocket), ордпу (genealogical tree), енби (talent), вирби (passion);

2) linguistic calques – from Russian language: вужвойтыр < (native people), асдон < (prime cost), асвеськöдлöм < (self-government), уджлун (workday unit), from Finnish language: луннебöг < (päiväkirja), уджъёрт < (työtoveri), кывбуралысь < (poet); (runoilija), from Estonian language: шöркыв (communion) < (kesksõna), from English language: öтуввез < (Internet), коксяр < (football), from German language: кадакыв < (Zeitwort), from Latin language: инним < (place name);

3) semi-calques – телепос (teleconference), киномойд (fairytale film), комбисёян (compound feed), вöрпромовмöс (logging company), вöрпункт (lumber camp), аэроöзын (airport), артби (artillery fire);

4) new meanings of words – котыр (family and organization), бала (project), куд (budget), петас (book volume, tele- and radiobroadcast), суйöр (state border);

5) dialecticisms: вöрпа (beast), пода (cattle), öныр (saddle), гöгапи (grandson), юрвеж (memory), йöрдöс (shirt);

6) activated archaisms: идöг (angel), сурым (death), кан (tsar), небöг (book), тупу (oak);

7) abbreviations formed for the first time: КМ газет – Komi Mu newspaper, ЕÖ – European Union, СКУ – Syktyvkar State University, КЛИИ — Institute of Language, Literature and History.

There are many barriers on the way of making neologisms active: language conservatism, resistance and counterwork of traditionalists, poor promotion of words in media, etc.,” the scientist said.

The attention of Yevgeny Tsypanov is also focused on emotiology, the science studying the methods of expressing emotions on all language levels. Pejoratives – representing one of Komi emotive lexicon sections – are of particular interest for the scientist from Syktyvkar.

When asked what the mechanism of forming pejoratives is based on, and how studying them helps restore the history of ethno-cultural areas, the linguist explained: “Many sections of the Komi language lexicon have not been studied at all, though there are many dictionaries. Naturally, it can be explained by insufficient manpower resources. There are few specialists studying the Komi language. The people belonging to older generation gradually go away, while the young ones either are reluctant to deal with postgraduate studies, or fail to defend their theses. From our perspective, pejoratives include not only abusive expressions, but all attitudinal words and word combinations having negative connotation. From this point of view, there is a lot of material. One can identify two large groups of words in pejorative lexicon: these are lexemes or lexical units with initially attitudinal semantics (йöй, бöб (fool), вежöма (werewolf), гуысь (thief), гиги (person laughing without reason all the time)), and lexemes with diachronically figurative meaning, different from direct or primary denotative meaning. Such pejorative units have emerged as a result of word meaning extension, as the phenomenon of polysemy development. For instance, pejoratives катша (babbler, flibbertigibbet) and нямöд (dawdler, weakling, spineless creature) came into existence by way of denotative meaning replacement and metaphorization (with respect to similarity of behavioral plan and physical characteristics, instead of formal resemblance) on the basis of primary meanings magpie and foot wrap.

In the Komi language, we can identify two clear groups of words with pejorative co-meanings having come into existence on the basis of their primary meanings. These are lexemes meaning: 1) human body parts, body wastes, 2) objects of traditional farming and household, 3) zoomorphisms, names of animals, birds, insects, reptiles, fish, 4) phytonyms, names of plants and their parts 5) proper names (ethnonyms, personal names), 6) mythological lexicon (names of ghosts, various negative creatures, etc.).”

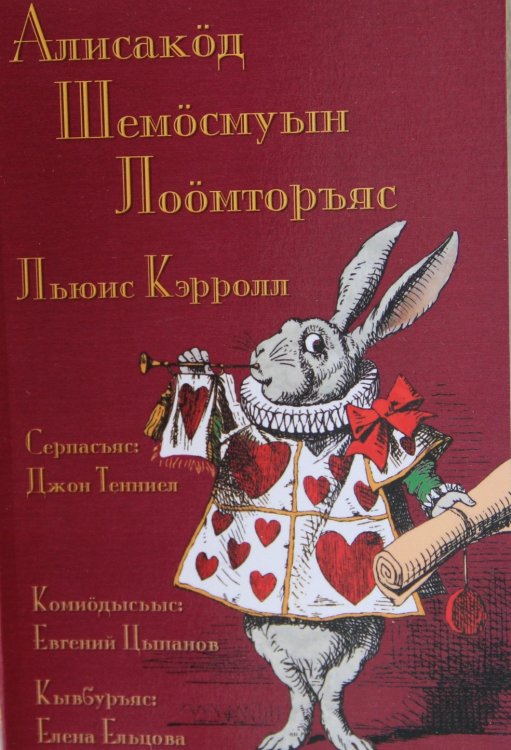

You translated into Komi-Syryenian language Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, a classic English-speaking book for children, didn’t you? Was it your first experience of such work?

“I have translated fairytales and stories for kids from Estonian and Udmurt languages before, and my translations were published in newspapers and magazines. Besides, the book by famous Estonian children’s writer Eno Raud about puppet Sipsik that came alive was published at the expense of a sponsor’s money. The idea of translating Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was suggested by the representatives of International Lewis Carroll Society. The book was translated in cooperation with the editor, famous Russian poet and translator Victor Fet living now in the USA,” Tsypanov specified.

It is important that the translated fairytale can be read both by Komi-Syryenian and Komi-Permyak people, as the authors have used similar literary variants of languages. Nevertheless, the translators neither backed the idea of domesticating the text (with the exception of introducing traditional Komi names of monetary units: ур along with pence and шайт along with pound), nor added folkloric coloring to the fairytale having retained the atmosphere of English-speaking country and time.

They met with no serious problems while trying to convey the text meaning using morphological and syntactical means of the Komi language. According to Syktyvkar-based scientist, “the main difficulty lay in choosing adequate translation for play of words, various poems and songs, as well as the material based on English realities.”

Famous book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll translated into the Komi language – Алисалöн Шемöсмуын лоöмторъяс. Evertype Publishing

Translation authors, employees of the Institute of Language, Literature and History at Komi Research Center of Ural Subdivision of RAS Y. A. Tsypanov (prosaic text) and Y. V. Yeltsova (verse). Editor-adviser – poet and translator Victor Fet.

“I have also translated from Russian The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupery, but cannot still find sponsors to publish it as a separate volume. In general, there has been no dedicated financing for publishing books in translation in the republic since early 1960s, the time of Khrushchev’s reforms. The commission for selection of socially important literature gives preference to the republican writers, yet there is not enough money even for publishing their books,” the scholar stressed.

Yevgeny Tsypanov takes part in the work of Term-Spelling Commission under the National Policy Ministry of Komi Republic (by the way, it functions on a pro bono basis, i.e., no remuneration is paid to its members). The commission deals with the creation of new terms and terminological combinations, correction of translations, and discussion of various points at issue. According to the scientist, “the very work aimed at promoting the Komi language in public sphere is not determinative, though the commission’s activity is productive enough. The key problem lies in a different aspect: the republican authorities have no political will to execute the law on languages in full measure and expand the functions of language in the society, though on paper vigorous activity has been developed, and everything is boiling over. Let me quote just one example: over many years, Komi national movement has strived for execution of the law paragraph dealing with universal and mandatory teaching of the Komi language at the republic’s schools, and serious results have been achieved in this field over the past years. However, after Vladimir Putin gave the go-ahead, and new federal bylaws were adopted, it became possible to teach native languages (with the exception of Russian) in Russia subject to availability of written application on the part of parents with choice of program. The Education and Science Ministry of Komi Republic stood at attention, which eventually undermined the status of the Komi language in education system. This academic year, for instance, the Komi language as a native one has been learned at 67 schools (21% of all schools) by 4,023 school children (4% of all pupils), while the Komi language as the state one has been learned at 158 schools (50% of the total of them) by 24,651 pupils (24%) – from the report of Komi Mu newspaper, issue dated April 1, 2021. Put it differently, the republican law has been overridden by the federal act, which speaks volumes about the sovereignty of republics being constituent entities of the Russian Federation. Only one conclusion can be made: there are more problems than prospects so far.”

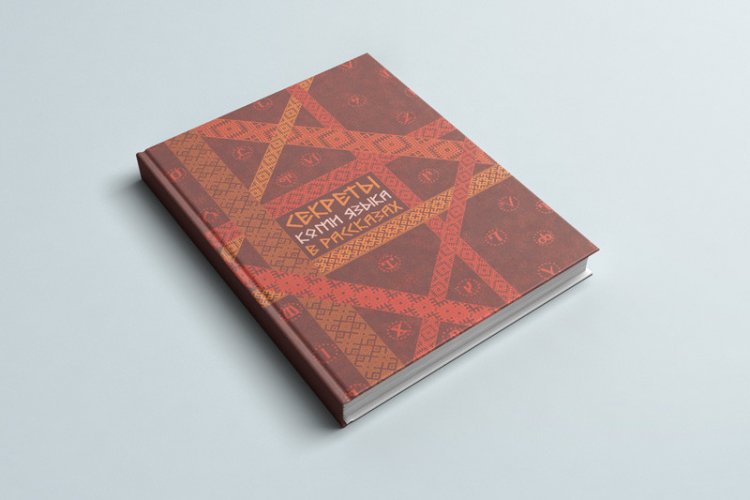

Last year, a factual book written by Yevgeny Tsypanov in co-authorship with his colleagues from ILLH came out with the financial support on the part of Komi National Policy Ministry. It is a collection of stories about the singularity of the Komi language, the specifics of its orthoepy, grammar, syntax and vocabulary. The publication is aimed at stirring up an interest in learning the language of the republic’s native people.

Factual book by the employees of language sector of the Institute of Language, Literature and History at Komi Research Center of Ural Subdivision of RAS: Y.A. Tsypanov, O.I. Nekrasova, G.V. Punegova Secrets of Komi Language in Stories. Moscow, 2020.

What about the current work aimed at popularizing and promoting the Komi language (including projects, target programs and activities)?

“This work looks languid enough, which can be explained by the fact that a social order on the part of republican ministries and departments is missing. The teachers of the Komi language at Syktyvkar State University are few and have no time for it, while the linguists of our institution have been obliged to write Higher Attestation Commission’s and Scopus articles. The popularization of the Komi language has become the activity of few individuals. Even Komi-speaking newspapers reluctantly print the materials devoted to the Komi language, as they have different priorities. Some radio and television journalists show interest in the problems of the Komi language. Among the activities aimed at promoting the language we can single out research and research-to-practice conferences, periodically organized congresses and forums of Komi peoples, Komi-speaking televised games, like What, Where, When? and Club of the Cheerful and Sharp-Witted, as well as the events of Komi youth organization Mi (we) and active stuffing of the Internet with Komi-speaking resources. A great number of literary and scientific texts have been already digitized posted online. The main work in this area is performed by the Interregional Laboratory for Information Support of Finno-Ugric Languages under the National Policy Ministry of Komi Republic (fu-lab.ru). Thanks to the Internet, the resources of the Komi language, Komi-speaking programs, songs, plays, films, newspapers, and books have become accessible everywhere, on all continents,” Yevgeny Tsypanov specified the current problems of promoting the Komi language.

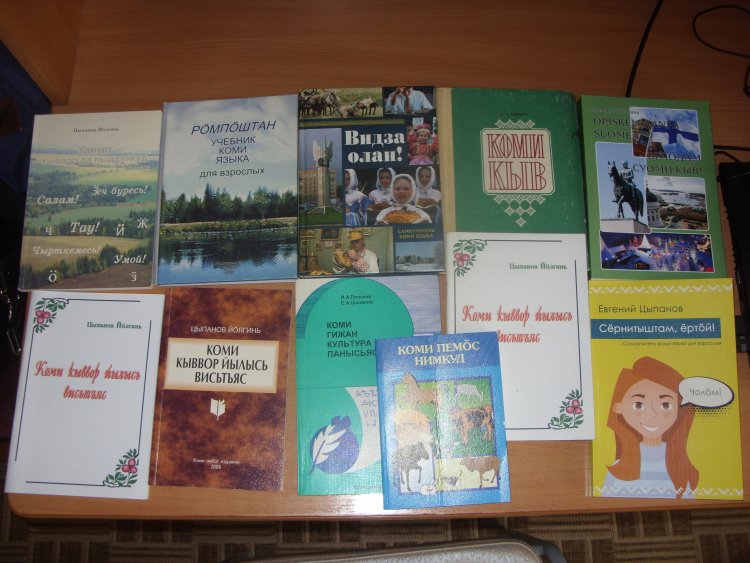

Learning aids and factual editions of which Yevgeny Tsypanov, head of language, literature and folklore department at the Institute of Language, Literature and History at Komi Research Center of Ural Subdivision of RAS is the author or co-author.

How can you describe the status of Finno-Ugric languages, Komi one in particular, in the Republic of Komi and the prospects of language tradition passing mechanism?

“I will be brief: In 1992, the Komi language was declared a state one in the Republic of Komi along the Russian one by a special law. However, despite little increase in the Komi language’s presence in business sphere, the law does not work at full capacity, and those in power seldom mention it. There are prospects of keeping the language, yet on conditions of translating it to the younger generation in families and teaching at school. In development and preservation of language, Komi people should become the main factor with active participation on the part of state authorities,” Yevgeny Tsypanov, employee of Komi Research Center of Ural Subdivision of RAS expressed his opinion.

The careful attitude toward ethnographic and cultural heritage has formed the traditions of Finno-Ugric linguistic school and is aimed at preserving the national distinctness of oral and written languages, as well as the literature of national minorities. Information support from the state and society is especially important – the popularization and national-language policy in the Republic of Komi should assist to the development of Komi ethnos.

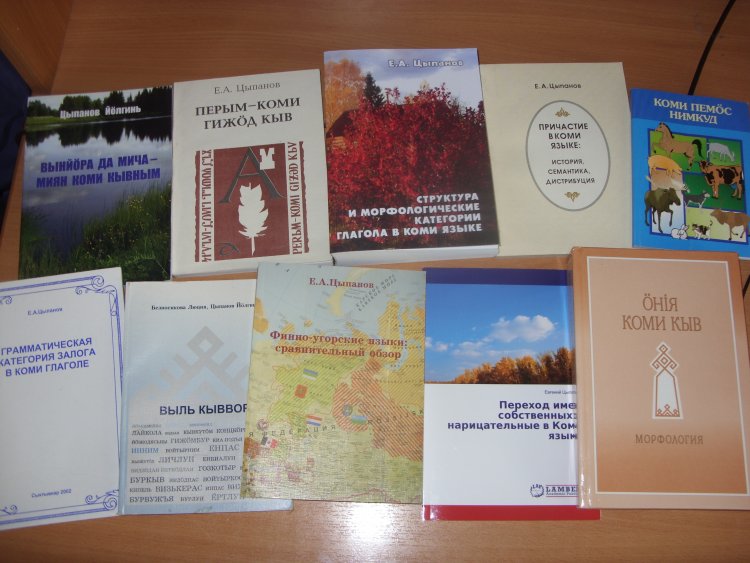

Scholar books by Y.A. Tsypanov (including the ones written in co-authorship) devoted to issues of studying language specifics of Komi peoples.

All photos and pictures are provided by Yevgeny Tsypanov