A few dozen first cries of newborn babies are heard every day in Moscow on Oparina Street, 4. The Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology has been involved in the emergence of many new lives for almost 80 years. Today, with the advance in science and medical technologies, even those who no longer hoped to hear the voice of their child can feel the joy of motherhood and fatherhood. Academician Gennady Sukhikh, M. D., Head of the Research Center, on genetic research opportunities, the challenges of the pandemic, and the immensity of evolution.

— You are the director of the only National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics and Gynecology in Russia. This medical field is of national significance. Why don’t we have such centers in every region, at least in major cities of the country?

— The question is both simple and complex. It all started on January 6, 1944, when part of the USSR was still occupied by Germany. The government under the leadership of Stalin signed a decree on establishing the Institute for the Protection of Motherhood and Childhood. The name of the institute and its subordination have changed several times since then. We were subordinate to the Ministry of Health of the USSR, then to the Academy of Medical Sciences of the USSR, the Russian Academy of Sciences. Finally, the center is again subordinate to the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Over these years, we have tried to maintain the unique status of the leading research, educational, and medical institution.

In 2017, the Ministry of Health started establishing national centers and now there are 36 of them already. We’ve got as many as four research centers dealing with oncological issues. This is a very important medical field, which has been widely discussed over the past decade. Along with cardiovascular diseases, this field will always be prioritized in research and clinical practice. However, Russia is facing demographic problems today: excess mortality and population decline. These are critical issues, especially in the COVID and post-COVID era.

Our Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology has always been the largest institution in Russia. We have managed to create a network of leading organizations that functions properly in each of the 85 regions of the country. As a rule, these are perinatal centers of regional importance. Next, there are city-level maternity hospitals or a group of such hospitals. Finally, there are also primary care services.

Relevant institutions throughout the country operate under our leadership. The center’s mission is to control rather than manage as well as to stay aware of the situation in all 85 regions of Russia.

In March, my colleagues unexpectedly arranged a celebration for me. It turned out that I have been the center’s director for as many as 15 years. Time flew by very fast. Just three years ago, I was much concerned about our collaboration with the regions. Thanks to my excellent employees, including Marina Shuvalova, the deputy in charge of regional relations, we have visited all 84 regions of the country, besides Moscow.

Each region was visited by a strong team of professionals that comprised an obstetrician, an obstetrician-gynecologist, a neonatologist, an oncologist, an intensive care specialist, a health administrator, and a nurse manager. Such visits typically included a four-day intensive tour around regional and major city-level institutions. Before leaving, the team had a meeting with the leaders of the regions: the Health Minister, vice-governor, or the governor’s deputy. We do not view these meetings as inspections or audits, but rather as friendly visits built upon complete honesty, critical analysis, and awareness. We must identify the strengths and weaknesses, but also tell the regional and federal authorities about the outstanding results. I believe it is comforting for the staff in regional institutions to know that they are the best in some aspects in this huge country. This does honor to the national center as well. I think this is the right attitude.

Today, the national center is responsible for both the transfer of the best practices and the development of clinical guidelines.

— What are these guidelines developed for?

— Clinical guidelines are a roadmap for each individual case. They explicate every step a doctor takes, propose solutions for each situation, and describe the necessary drugs and equipment. If doctors follow clinical guidelines, they are on the route to success.

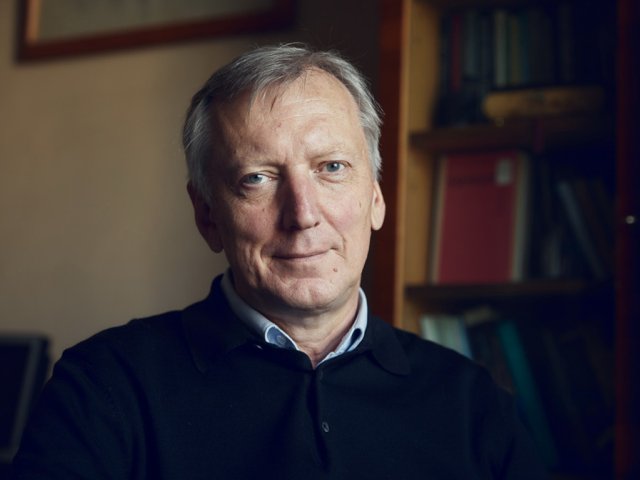

Academician Gennady Sukhikh, Director of the National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology

Clinical guidelines are especially important in obstetrics, which is a very complex medical specialty. In many types of surgery, a specialist runs the risk of losing one life, whereas, in obstetrics, two lives are at stake: those of the child and the mother. Therefore, obstetrics is an amazing specialty that brings together a whole spectrum of subspecialties.

Oncogynecology is yet another significant area for us. Today, more than 40,000 women die every year from breast, cervical, and ovarian cancer. This encouraged us to start working in the field of oncogynecology.

As for infertility, we must take into account both female and male factors. Let me remind you that in 1986, a girl named Lena was the first child born in the USSR as a result of the use of assisted reproductive technology in our center. In fact, 21 years later, she also gave birth to her wonderful son Slava here in the center.

Back in 2009, I realized that we were missing a program of assisted reproductive technology, what is today known as in vitro fertilization (IVF). And three years ago, we felt that even this was not enough for us. A third program appeared, and all areas were merged into one Reproductive Medicine Institute, which now includes andrology, a field of medicine that deals with men’s health.

Today, the National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology has developed a complex interdisciplinary conglomerate, the growth of which would be impossible without brilliant specialists such as cell biologists-embryologists. They have a unique opportunity to see life from its first minutes. Today, on a par with global practice, we grow an early embryo for five days to the blastocyst stage, then, transfer it to the future mother or continue with cryopreservation.

Another significant area is neonatology which, among all else, deals with the birth of children with extremely low body weight, that is, less than 1,000 grams.

— Until recently, it was believed such children were doomed to death. Where do we stand today?

— November 17 celebrates World Prematurity Day here at the center and globally. This is one of the most emotional events. We are visited by mothers and their children such as Yulia (birth weight 497 grams), Kirill (birth weight 654 grams), and others. Some kids read poetry, others dance or sing, and their mothers look at them and feel happy. Each child knows that they spent three or four months after birth here before they were discharged home with a weight of 2.5 kilograms already.

And you’re right: it wasn’t always like that. Over the past 20 years, neonatology has fundamentally changed, as have the approaches to the intensive care of premature babies with an underdeveloped respiratory system.

I can’t help but admire my colleagues from the neonatal surgery department. This department was created thanks to the initiative of Academician Vladimir Kulakov. Today, many children with detected malformations of the anterior abdominal wall, kidneys, lungs, diaphragmatic hernias, and cardiovascular system undergo surgery here, at the center. We are a role model for other large neonatal and perinatal centers as they try to establish similar departments.

— How has your center coped with the pandemic challenges? In your video message, you said that you would not allow for a scenario where the center stops functioning and the specialists are out of practice. How was work organized at this difficult time?

— The last two years have been challenging. With the pandemic outbreak, a red zone was organized in the center. There was a hospital for 190 patients. Among the total flow — about 900 patients — we treated 67 women in a state of pregnancy.

Also, our colleagues advised the entire country 24/7. Sometimes one would process 90 requests a day. To compare how tough it was then and how smooth it is now, we have processed only four requests over the past 24 hours.

— In the summer of 2021, doctors reported an increase in severe cases of COVID-19 among pregnant women. How are things today? And what does the medical community know about the impact of the disease on mother and fetus?

— I can’t say I am very comfortable recalling the tension we felt at the end of 2020, especially in 2021, when the Delta variant dominated. In general, we lost more than 100 women across the country in 2020, and even more in 2021, since the new variant was highly virulent, contagious, and also had a serious effect on many functions and parameters of the body.

Over these years, we have developed specific protocols and guidelines for the management of COVID-19 during pregnancy. Employees of the National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology have done a tremendous job. Along with this, studies were conducted on the impact of severe infection on female and male reproductive systems. And when the first vaccines were introduced, the impact of vaccination on women’s and men’s health was also actively studied.

All these projects are ongoing. In the last 24 hours, 24 babies were delivered. Among them, five mothers suffered from the disease at different stages of pregnancy. Fortunately, the transmission of infection from mother to fetus is quite rare.

The center was the first to recommend vaccination to pregnant women and women who have given birth. Practice suggests that even in the case of coronavirus infection, the disease progresses much more favorably.

— In one of your comments, you made an interesting remark that evolution protects us and the human reproductive system does not suffer dramatically. How can you explain it?

— I just wanted to emphasize an immensity of our evolution. We are surrounded by many viruses, bacteria, and fungi. We, that is, human beings, are mammals and multicellular. Our body is made up of about 250 types of cells. The first multicellular organisms appeared about 2.1 billion years ago. And they had to survive and coexist with the world of bacteria and viruses. The goal of evolution was to carry genetic information through millions of millions of years. Could evolution disrupt this process? No. The endless confrontation between the multicellular world and the world of microorganisms, viruses, and bacteria goes on. But this confrontation is associated not only with losses but also with gains.

We have encountered much more dangerous viruses than SARS-CoV-2 in our biological background. However, we have survived because evolution gave us defense mechanisms. It could not leave humanity unarmed. I believe the current infection will not be fatal for us, as well as subsequent encounters with viruses. There is a lot of justified optimism in this. However, we can’t escape reality. People are accustomed to thinking not in evolutionary terms, but in very concrete ones.

— I cannot but ask a few questions that seem to be particularly important now that there is a large amount of pregnancy planning information available. What are the role and potential benefits of genetic tests today?

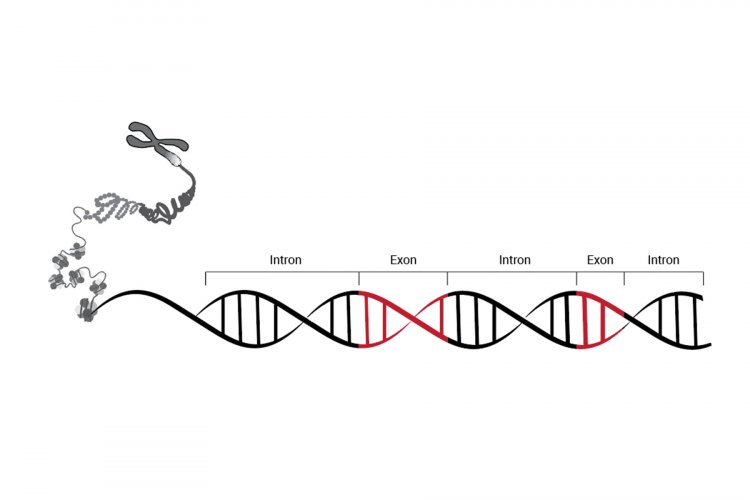

— Indeed, what seemed to be some sort of science fiction 20 years ago has become commonplace today. Scientists first deciphered the human genome at the turn of the new millennium. Today, we analyze the exome here at the center. This is the part of the genome involved in protein-coding. They are responsible for our phenotype, receptors, and cells. A person has about 180,000 exons, which is approximately 1% of the genome size. Interestingly, about 85% of the deviations that cause hereditary diseases occur in this part of the genome. Each newborn receives a book with a personal genetic profile at the center.

Exome sequencing would be the most cost-effective approach for sequencing the targeted coding region of a genome, a region that comprises 1–2% of the genome but represents 80–90% of variants found in the entire genome

— What insights do parents get as a result of such research?

— As a rule, exome sequencing helps to detect the presence or absence of genetic mutations. For example, it can show that an unborn baby, fortunately, has no monogenic diseases such as spinal muscular atrophy or others.

But there is a downside to everything. For example, by analyzing parts of the genome, a doctor understands that a child has certain characteristics and predispositions. How can we tell the happy parents who have been involved in pregnancy planning for the last 5-10 years that due to gene mutations, their daughter falls into the group of females who are eight times more likely to develop breast cancer and — even more often — ovarian cancer? This is a serious ethical dilemma.

Then, in the 2000s, I thought to myself, “Oh my God, the first genome has been sequenced! It opens so many opportunities in terms of knowledge, prompt diagnostics, and accurate patient treatment at a more profound level.” And then came the understanding that nothing ends with genome sequencing. After all, there is also gene expression.

Imagine that a genome is a poem by Marina Tsvetaeva. It can be read in the voice of the talented Veniamin Smekhov or in an opposite manner, stuttering with wrong placement of accent marks and pauses. This will leave us with two different texts. The scientific community realized this, and so epigenetics appeared that studies heritable changes in gene activity, that is, the errors in gene expression that lead to the development of a tumor process for example.

And here we ask the question again: Is epigenetics the final stage of scientific development? Of course, not, and the best illustration here is the advances in cell biology.

I recall a book by a great scientist Eugene Sverdlov called Observing Life through the Genome Window. At the end of each chapter, he asks the question, “Are we one step closer to understanding what life is?” No answer follows. No one has ever created a living cell. All efforts in this field only result in the creation of some primitive alternatives.

— Is infertility no longer a sentence?

— Sure. The era of assisted reproductive technology has begun in the late 1970s. Every year, we perform about 6,000 stimulations at the Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology. Of these, about 30% are considered potentially successful, that is, about 1,500-2,000 children are born.

However, assisted reproductive technology will never be a solution to the demographic problem. This is a highly sensitive humanitarian issue, especially for a family that has lost hope of hearing the cry of their newborn baby.

Infertility is not a sentence. The more actively science develops — both genetics and cellular technologies — the better we understand the mechanisms of the endocrine and reproductive systems and the fewer there are situations where we see no way out. Today, reproductive health is the niche, in which the latest achievements in molecular and cellular biology, genetics, medical technology, and pharmacology are applied.

In the past, very little attention would be paid to men’s reproduction. Fortunately, now the situation has changed for the better globally. It is impossible to create a new life without this. Evolution elaborated the female reproductive system and paid less attention to the male reproductive system. At the same time, men are 30% more responsible for subfertility, that is, for male infertility. And I am very glad that many treatment and diagnostic technologies for men’s health are being developed and actively used in healthcare, including our center.

— Does the age of the mother and the father affect fetal pathology?

— Yes, it does. Nature has seen to it that by the age of 40 a woman would stop having children. Of course, there are many examples of children being born in the 50+ and 60+ age groups. However, the question is as to the type of the generation that will be produced. It is an evidence-based recommendation that both men and women should accomplish their reproductive goals by the age of 45.

In this regard, delayed motherhood health programs have appeared in many countries, including Israel, Western Europe, the United States, and Russia.

As you know, modern women earn two or three university degrees, build their careers, and get married later. Of course, each situation is unique, but if a woman has no opportunity to give birth: she does not have a partner or there are some health risk factors, they should use the assistive reproductive technology program and freeze their egg cells in a medical bank or, for example, spermatozoa, in men’s case. I think that such assets are much more valuable than those kept in a Swiss bank.

In the 21st century, women increasingly opt for giving birth at the age of 30-35+. This option has its pros and cons, the main of which is a decrease in the quantity and quality of germ cells

The oocyte bank allows you to postpone pregnancy planning without worrying about the age-related or pathological decrease in the number and quality of germ cells and the associated risks for the health of the unborn child

The oocyte bank allows you to postpone pregnancy planning without worrying about the age-related or pathological decrease in the number and quality of germ cells and the associated risks for the health of the unborn child

— Several years ago, the whole world was shocked when the Shenzhen University professor He Jiankui succeeded in creating genetically modified children for the first time. Thanks to the intervention of geneticists, the twin girls have an innate immunity to HIV infection, he claims. Do you approve of such interventions?

— Yes. Genome editing has caused much controversy. But we must distinguish between the editing of somatic cells and that of reproductive cells. We have been actively working on editing reproductive cells since 2017. And the first publications also caused great emotional and ethical debates in the light of our Chinese colleague’s research. Imagine that both future parents have a gene responsible for absolute deafness. This means they will never have a child who can hear. Why can’t this be considered medical grounds for the use of genome editing techniques? Sadly, the world is not ready for this yet.

I’m sorry to hear that society is serious when discussing the creation of biologically enhanced humans with outstanding health. But it’s too early to talk about this. At the same time, genome editing techniques are a huge step in science and medicine. I think such research at the international level would be a good reason to move from sanctions to collaboration.

— You have been heading the center for 15 years. Can you recall the very first day in your new office?

— I remember that I was to go to the conference room and take my seat, not the familiar last seat in the second row, but the one at the council board, in front of a large audience. Now I am used to it but it felt very uncomfortable then.

— Did you feel responsible for such a large institution?

— That’s hard to say. Of course, I did not think, “What a huge responsibility lays on me from this moment!” After all, it’s about the routine, meetings, and work. Perhaps, someday I will say that those were very happy days. People needed me. I was engaged in work all the time. There were very talented and important people around, the people whom I admired and knew that each of them was better than me in something. Isn’t it a joy to see such a powerful team around you?

— There is a common expression “the miracle of life.” What is the miracle of life for you?

— Here is what I have noticed lately: when I see parents with newborns in my office and take their baby who is five days old, it feels more emotional than it used to be 10-15 years ago. I more subtly feel this miracle of life that will continue into the future. What will it be like? What will the future be? Perhaps, the baby I am holding at this moment is a future talented musician or an artist, or a person who will solve the mysteries of the quantum world. This is a mystery, a book that will be read but not by you. Hopefully, it will be interesting, thick, long, and very useful.

The interview was taken with support of the Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education and Russian Academy of Sciences.