Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of death worldwide. And today the situation is complicated by the pandemic and the impact of COVID-19 on the healthcare system. But in addition to common diseases, there are also rare genetic pathologies for which treatment approaches have not yet been formed. A young scientist, cardiologist Yulia Lutokhina, together with colleagues from Sechenov University, is researching different types of cardiomyopathies in order to improve approaches to their diagnosis and treatment. Read the interview with Yulia Lutokhina about the beginning of her path, the impact of the pandemic on medical education, and the importance of continuity in medicine.

Yulia Alexandrovna Lutokhina is a Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Faculty Therapy No. 1 of the I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University.

− Why did you choose medicine and cardiology? Are there people among your medical colleagues or historical figures that you look up to?

− For me, medicine is primarily an opportunity to help people. Since childhood, I have been surrounded by doctors who devoted themselves to their patients. My paternal great-grandfather was a military field surgeon. He went through the whole war and was awarded the Order of the Red Star, medals “For the Liberation of Prague,” “For the Capture of Budapest,” “For the Victory over Japan.” My grandmother on my mother’s side was an outstanding obstetrician and gynecologist, Honored Doctor of the USSR. She organized medical care in the Arctic, operated on people in a chum, in a helicopter, got to her patients on reindeer and dog sleds, and then, later, created an obstetric service in the hero city of Sevastopol. Then her work was continued by my mother – a wonderful, talented obstetrician and gynecologist. And even when I was born – and I was born in the hero city of Sevastopol – a small note was printed in our city newspaper Glory of Sevastopol, which was called Yulia’s Profession. It said that “another obstetrician and gynecologist was probably born in our city today.”

Meanwhile, events unfolded a little differently. At school, I studied in a physics and mathematics class and planned to enroll in MIPT. I was very interested in exact sciences and participated in the Olympiad movement. And it is quite possible that I would have entered MIPT if not for a good friend of our family, academician Nikolay Alexeevich Mukhin. It was he who, with his incredible authority, charisma, and attitude to his profession, convinced me to enroll in the First Medical University and become a therapist. (I note that all the staff of the Department of Faculty therapy are primarily therapists, although each of us has a narrower specialization). So, Nikolay Alexeevich became a wise mentor for me for the entire duration of my studies.

The choice of specialization was influenced by my physical and mathematical school education. I was very interested in the processes of electrophysiology in the heart, the causes of rhythm disturbances, conduction, arrhythmias. Therefore, I chose cardiology as my specialization, which finally fascinated me after practicing in the cardiac intensive care unit in the third year. Nikolay Alexeevich Mukhin sent me to the V.N. Vinogradov Faculty Therapy Clinic, where I work to this day, to my wonderful teachers – Alexander Viktorovich Nezhev and Olga Vladimirovna Blagova.

Being a cardiologist, I can fully realize my desire to help people. As you know, cardiovascular diseases still remain the main cause of mortality. Now we have set an ambitious goal of the Healthcare national project to reduce mortality from circulatory system diseases to 450 cases per 100 thousand. I am sure that every cardiologist in our country is working for the benefit of this project, for the benefit of our society.

If we talk about those medical colleagues that I look up to, tamong them, of course, are my teachers – my relatives and mentors, Nikolay Alexeevich Mukhin, Alexander Viktorovich Nedostup, and Olga Vladimirovna Blagova. When I took my first steps in medicine, one thing struck me: in the offices of our leaders, professors, heads of the department, there were portraits of not only outstanding personalities but also teachers.

This is very important for me because continuity is an integral part of the functioning of our healthcare. Although, of course, today I see portraits of teachers less and less, especially in the offices of young leaders.

− Why is it important to maintain this continuity?

− Because teachers teach not only how to diagnose and treat diseases. First of all, you need to learn from teachers a warm, kind attitude to patients, responsibility, and love for your work.

I was lucky enough to work at the Faculty Therapy Clinic. This is the oldest therapy clinic in our country – the successor of the First Therapy Clinic of the Medical Faculty of Imperial Moscow University. At one time, the clinic was run by such outstanding doctors as Mudrov, Zakharyin, Pletnev, and others. And each of them left their own legacy. Today, within the walls of our clinic, we try to preserve the traditions of our teachers in combination with innovative approaches in the diagnosis and treatment of patients.

− Your research paper on arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy was recognized as the best at the All-Russian competition of young scientists within the framework of the National Congress of Cardiologists. Tell us, what is the uniqueness of this work and what is known about this disease?

− Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy is a hereditary disease that affects the myocardium mainly of the right ventricle and is characterized by ventricular arrhythmias and, consequently, a high risk of sudden death. It is this disease that is recognized as the leading cause of sudden cardiac death in young people.

For some reason, there is an opinion among cardiologists that this cardiomyopathy is a fairly rare disease. According to various sources, the prevalence of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy varies from 1 per 1000 to 1 per 5000. But if you think about it, there are at least 2.5 thousand such patients only in Moscow. And for any doctor, every patient’s life is priceless, and for this life, of course, you need to fight. Moreover, we are talking about young, active people who are just starting to live. The peak of the manifestation of symptoms of the disease occurs at the age of 20 to 35 years, so it is extremely important to diagnose this disease on time and treat it competently.

In our research, we studied clinical forms of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy – something that no one had done before us since there was no generally accepted clinical classification of this disease. The study allows us to develop a personalized approach to patients, including on a genetic basis since the scientific work was carried out in close cooperation with the Laboratory of Medical Genetics of the Russian Scientific Center of Surgery named after Academician B.V. Petrovsky. This made it possible to carry out a DNA diagnosis of each patient.

In addition, we have identified additional signs that simplify the process of diagnosing this disease. I would like to emphasize that the diagnosis of cardiomyopathy is difficult since there is no single symptom that would allow us to say unequivocally whether this disease is present or not. We were able to find additional criteria that are quite easy to apply. They simplify the diagnostic process, allowing you to identify such patients among many others who turn to a cardiologist.

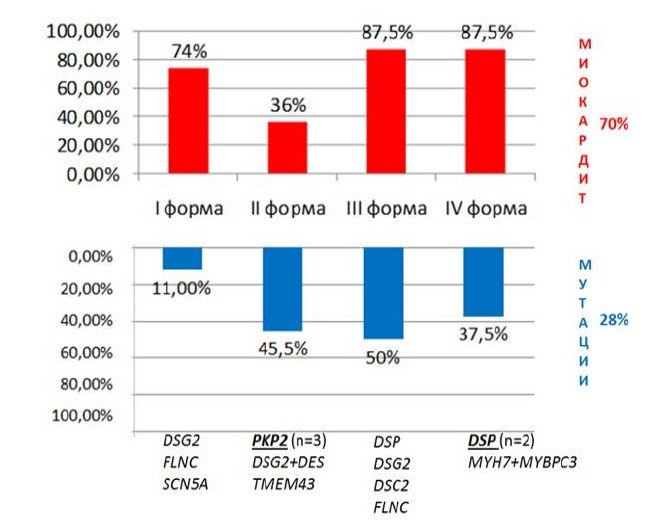

In addition, the highlight of this scientific work was the study of the role of concomitant myocarditis. There has been evidence in the medical literature that myocarditis can actually occur in patients with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. But we managed to establish its high frequency – we found concomitant myocarditis in almost three-quarters of patients. We also studied the role of myocarditis in the formation of the clinical picture, depending on the form of the disease. And, most importantly, we have shown that it can and should be treated, since the treatment of concomitant myocarditis in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy can significantly improve the prognosis of the disease.

The frequency of concomitant myocarditis (red) and mutations (blue) depending on the clinical form of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy of the right ventricle

− Can an ordinary person, analyzing their own symptoms, understand that they need to see a doctor and that, perhaps, this particular disease develops in the body?

− It is impossible to make an unambiguous conclusion about the manifestation of a particular disease on your own. There are specific symptoms, the so-called red flags, which mean it is necessary to consult a cardiologist. If we talk about right ventricular cardiomyopathy, then, first of all, sudden episodes of loss of consciousness for no apparent reason should alert, as if a person was in a stuffy room or stood on their feet for a long time (as in the case of fainting due to low blood pressure). It is especially important if such loss of consciousness occurs during physical exertion. Sometimes on TV, you can hear reports of sudden deaths of hockey players, basketball players, and other athletes. Often the cause is various cardiomyopathies.

Another significant indicator is ventricular arrhythmias on the ECG, which were detected during the medical examination. Sometimes it goes unnoticed. But with such rhythm disturbances, it is necessary to contact a cardiologist and find out: what is the cause of these symptoms, what is behind them?

And, of course, episodes of sudden death in the family, especially in young people, should cause concern. This is also a reason for contacting a cardiologist and for medical and genetic counseling.

− Do you plan to further develop this research and study other features of this disease?

− I continue to study this disease and maintain a database on arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. I would like to note that myocardial diseases are a completely inexhaustible topic and, perhaps, one of the most promising and dynamically developing areas in modern cardiology.

To date, combinations of various myocardial diseases in one patient are of particular interest. In particular, a combination of cardiomyopathy and myocarditis. The fact that genetic cardiomyopathy (not necessarily arrhythmogenic, but also other types) is a background for the addition of myocarditis is being actively discussed. Conversely, myocarditis, in turn, is a factor contributing to the implementation of an abnormal genetic program, if the patient has some mutations, breakdowns in DNA. Therefore, it is interesting to study this single continuum of the interaction of inflammation and genetics.

Last year the topic of my doctoral dissertation was approved. My work will be dedicated specifically to the combination of not only arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy but also other cardiomyopathies with myocarditis. I plan to investigate the role of inflammation in the clinical picture, in the prognosis, and also consider approaches to the treatment of such myocarditis.

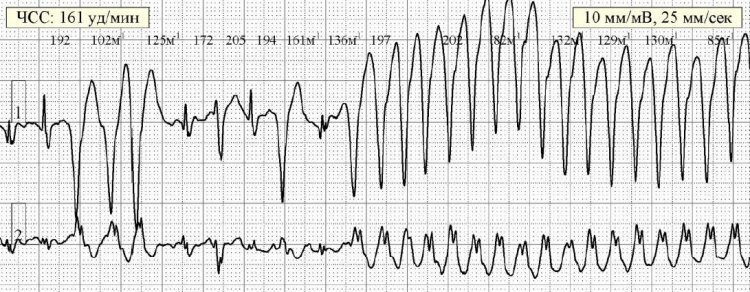

Rhythm disturbances in patients with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy of the right ventricle with a high risk of sudden cardiac death

− As far as we know today, the medical community is also faced with another important problem: the influence of COVID-19 on such diseases. What does the scientific community know today? Are you and your colleagues from Sechenov University working in this direction?

− This is exactly the direction that we are actively working on today with Olga Vladimirovna Blagova. We are studying post-COVID myocarditis, and the topic of coronavirus infection is something that cannot be avoided in any specialty right now.

By itself, myocarditis associated with viral infections is not new. It has long been known that the basis of myocardial inflammation can be both the direct damaging effect of cardiotropic viruses on the heart, and the development of autoimmune aggression against one’s own myocardium after an infection. However, little is known about myocarditis associated with the novel coronavirus infection.

To date, we reliably know from population studies that myocarditis has increased significantly since the beginning of the pandemic – by 16 times - which indirectly allows us to assume that there is a link between coronavirus and myocarditis. There is also data in the literature on myocarditis as a complication of the acute phase of infection. In our clinic, reorganized during the first wave into a COVID-19 hospital, similar cases were also observed.

But of particular interest is the so-called post-COVID myocarditis. This concept has not yet entered either our or foreign cardiology, but we are actively applying and studying it now. We are talking about myocarditis which develops after a coronavirus infection when the patient has already recovered clinically. It appears within one to eight months after the infection, on average 2-3 months later. The clinical manifestations of this myocarditis can be different: arrhythmic variants when after infection there are complaints of interruptions in the work of the heart, as well as myocarditis with a disruption of the contractile function of the heart. The latter manifest themselves in the form of symptoms of heart failure – the appearance of shortness of breath, edema, decreased exercise tolerance in patients without obvious reasons. At the same time, it is often difficult for a doctor to distinguish between shortness of breath after a coronavirus infection, since in many patients it is not associated with heart damage, but with post-inflammatory fibrosis after pneumonia, especially in patients who had significant lung damage. But, in any case, this is an occasion to consult a doctor for a differential diagnosis of shortness of breath after an infection.

It is important that in our study, the presence of myocarditis in patients was confirmed not only clinically based on indirect signs, but also during a myocardial biopsy. In many patients, we see coronavirus RNA in the myocardium. And after a long time after the infection – even eight months after recovery.

The presence of a viral genome in the myocardium of patients creates additional difficulties in the treatment of these patients. Nevertheless, we already have a positive experience in managing such patients. We see an improvement in their condition, and, of course, we consider this task one of the priorities.

As for Omicron, both our patients and our colleagues are now interested in it; so far we cannot say how often myocarditis develops after this variant. Too little time has passed yet. But I think that the data on this will appear a little later.

− Is there any age dynamics? Has the number of young patients with post-COVID myocarditis increased?

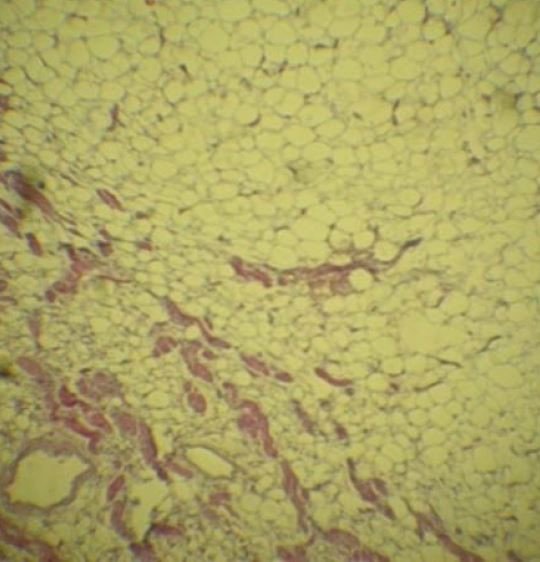

Replacement of the myocardium with fat and connective tissue in patient with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy of the right ventricle

− In general, myocarditis often occurs in young patients. It is also known that men suffer from it more often than women. Most likely, this is due to the peculiarities of the functioning of the immune system. So far, it is difficult to identify any age dynamics, since there are not so many patients at our disposal, but from population studies that simply compare the frequency of myocarditis before and after the pandemic, we see that the frequency of myocarditis has especially increased in the group of very young patients, including children under 16, and, oddly enough, in the group over 75, which, in general, is not quite typical.

But, of course, this is all very new and requires further study, verification, and comparison of different populations.

− You are a member of the International Association for Medical Education. Has the pandemic affected medical education? After all, as you know, numerous universities, including medical ones, have switched to distance learning.

−Yes, this is a very serious challenge faced by modern medical education. Medical education cannot be given in any way in absentia. This is absolutely impossible. As Evgeny Mikhailovich Tareev said, there is only one way to form a doctor: “a patient is a book, a book is a patient.” Unfortunately, in today’s conditions, students have only books left. And if such a situation had happened 20 years ago, it would have been impossible to continue any kind of medical education. Students would have to go on vacation due to the epidemiological situation.

However, today modern technologies come to our aid. Therefore, since the beginning of the pandemic, we have faced an important task – to prepare a large amount of content for the portal of our university in a very short period. We created new and improved existing video lectures, recorded videos with our patients so that we could show how the interviewing and examination of the patient was going on, supplemented this with presentations from medical histories that we had previously brought to classes to discuss the results of tests, instrumental studies, electrocardiograms of patients. In addition, we conducted webinars directly from the ward: we negotiated with patients, turned on the mobile phone camera, and broadcast. It’s nice that the patients treated this with understanding, everyone met us halfway, and personally, I have not encountered a single refusal of the patients to participate in such a distance education of future doctors. It seems to me that patients realize that the younger generation of doctors cannot be formed without having any opportunity to communicate with the patient. I am very grateful to our patients for their understanding and cooperation.

My colleagues and I really hope that after the pandemic we will be able to return to the roots and preserve the key principle of teaching Russian medicine “at the bedside.” This is especially important for clinical disciplines.

− You exchange experience with foreign colleagues. Is there a noticeable difference between medical education in Russia and abroad?

− I must say that any system inevitably has its pros and cons. Of course, in foreign medical schools, the approach is somewhat different from the Russian one. The fact is that in foreign medical practice, clinical protocols have been formed for all areas. They have developed a long time ago, but they are constantly being improved. However, there is a nuance: in non-standard situations, when an individual approach is required, the developed protocols do not always work. In Russia, even though we are also actively developing national guidelines for all specialties, the good old principle of treating not the disease, but the patient still remains. Therefore, our approach is somewhat closer to personalized medicine, which today is becoming the main trend in the modern healthcare system both here and abroad.

Another significant difference is related to the student’s personality. A medical student abroad is significantly older than a Russian student. As a rule, young people come to medical universities after graduating from college and in most cases pay their own tuition. And this is a completely different level of motivation compared to the motivation of Russian students who enter medical universities after school. This, of course, is a minus of our education system, and I must say that so far, the Russian system is more loyal to weak students. But the situation is gradually changing. Now the requirements for students and graduates are being tightened.

On the other hand, a positive aspect can be considered the fact that medical education is free in Russia, and, fortunately, available to the majority motivated students. A talented young man is very likely to have free tuition and will study well, receive a scholarship. This is something that our foreign colleagues cannot boast of.

Here I can share my own experience. At the end of the sixth year, I was a presidential scholarship holder and interned in Germany, at one of their oldest universities – in the city of Kiel, at the Christian-Albrecht University. There I was trained directly in cardiology, and my future husband, a neurologist, was trained in a neurological clinic. German colleagues were very happy to interact with us, they liked our approaches to the diagnosis of diseases. German doctors have limited use of physical examination of the patient. At the same time, I could go into the ward, look, listen, knock, and formulate something quite accurate regarding the preliminary diagnosis. Colleagues from Germany are still more focused on instrumental research, laboratory tests.

They were actively offering us to stay at this university clinic, graduate from their university, take exams and continue working in Germany. But we returned, graduated from our wonderful Sechenov University, and continued to work in our country. Since then, I have often been asked the question: “Why didn’t you stay abroad? You two were offered to stay at the oldest university. Why didn’t you want to work there?” In my opinion, this is a completely incomprehensible question. My country gave me excellent free higher medical education. Then I completed my internship in therapy, residency, and postgraduate studies in cardiology for free. My country taught me, gave me excellent education for free. Why should I apply all the acquired knowledge, skills, and abilities in another country? I don’t agree with that! That’s why we came back, and I don’t regret at all that I returned to Russia and continue to work here.

By the way, a curious situation relates to this. In Europe, there is still an outdated view of our country. A few years ago, my husband and I were interviewed by a journalist from Norway. Communicating with us, a family of two young scientists with a small child, he expected to see a desire to go to Europe, but instead found two enthusiastic young doctors who are happy to go to work. The journalist, of course, was extremely surprised. On the other hand, we are very glad that we were able to change his idea of Russia, of Russian science.

− A wonderful story. And if we talk about medical science, are there any differences in research, perhaps in the approach to it?

− It seems to me that the Russian medical science, after the failure in the 1990s, has long reached the world level, and in many ways, this is facilitated by active grant support from the state. It manifests itself in the financing of both fundamental and clinical research. I had an interesting opportunity to compare our scientific approaches with foreign ones because as part of the international cooperation of Sechenov University with University College and Imperial College London, my colleagues and I from the university completed a course that was dedicated to an in-depth study of the methodology of biomedical research. I can say that Russian scientists use advanced approaches in research, and they differ little from those technologies that are used abroad. So, we keep up with the times, while we have our own interesting trends and unique directions.

Perhaps, the so-called scientometrics can create a false impression about the lag of Russian science. Today, everyone likes to evaluate the H-index, citation, and analyze various indexes in international systems. But, in my opinion, the scientometrics system is far from always adequate and in its current form even hinders the development of Russian science, since Russian scientists are required to obtain high indexes in foreign systems.

Let’s imagine that Americans or, for example, Germans are told: “Guys, you have low RSCI (Russian Science Citation Index). You’re not working well.” And this is exactly what Russian scientists face when they are evaluated using Scopus or Web of Science databases. A huge amount of effort and time of medical scientists is spent on meeting the requirements that are often formulated by the administration. Of course, the citation of our scientists in foreign systems is growing, but I am not sure that this is the only correct approach. I think that it is necessary to approach this issue more flexibly and consider, among other things, publications in Russian scientific journals.

− I am interested in your opinion on telehealth. How effective do you think it is in the current conditions and does it have further development?

− I am sure that telehealth will continue to develop since it appeared even before the pandemic. This is due, among other things, to the fact that Russia is a big country, and it is not always possible to quickly send a patient to a federal center.

Telehealth does have several advantages, but it is necessary to be competent and careful about its implementation. Telehealth is not always a contact between a patient and a doctor. In my opinion, the interaction of a doctor who leads a patient in the regions and an employee of a federal medical center who specializes in a specific area can be considered more optimal. In my opinion, in telehealth consultations, the effectiveness of doctor-doctor interaction is higher than doctor-patient interaction.

− Yulia, what are you working on today, in addition to the already mentioned research?

− We continue to investigate various diseases of the myocardium and pericardium, and today, in addition to my doctoral dissertation, I study heart lesions in the framework of coronavirus infection.

− A doctor is always perceived as a person who gives all their strength to patients. Do you have time for hobbies? And do you have any free time at all, which sometimes everyone lacks so much?

− I will be honest and say that I have practically no free time. However, I concluded that, no matter how much I love my job, productive work always begins with rest. Therefore, I try to forcibly allocate time in my schedule for rest and my hobbies, just as I allocate time to work with patients and students.

My favorite hobby is playing the piano. I have been playing the piano since childhood, and even as a student, I took lessons from a wonderful teacher of the Moscow State Conservatory. It gives me great joy. Of course, there is practically no time left for classes now, but I can’t deny myself the pleasure of playing music. But, of course, this is not always possible, because the piano, with all its advantages, also has disadvantages – it cannot be played at 6 AM and 11 PM. And this is exactly when I have a free minute. So, I decided to find quieter hobby options that allow me to relax. This year I tried myself in watercolor painting and found this activity very exciting. The most important thing is that it is quiet and possible at night.

And, of course, for a person whose work relates to a sedentary lifestyle, sports are important. I have been doing wushu for many years, and it also brings great joy and allows me to keep in shape.

I also like to cook. And now the culinary process has acquired some new shades, because now my daughter, who recently turned 5, is helping me. And, by the way, she says that she also wants to become a doctor, which, in general, is probably not surprising for our family. However, she wants to become a dentist. So, we will expand the range of specialties in our family, unless, of course, she changes her mind and chooses some other path.

Photos and illustrations provided by Y. Lutokhina.