“The day of Christmas eve ended, and the night began, cold and clear. The stars and the crescent moon shone brightly upon the Christian world, helping all the good folks welcome the birth of our Savior. The cold grew sharper, yet the night was so quiet that one could hear the snow squeak under a traveler’s boots from half a mile away.” This is how Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol begins his narration, taking us with him into a fabulous, fantastic world in which reality collides with mysticism as in a nativity theater. Talentedly weaving funny humor, irony, and elements of satire into the plot, Nikolai Vasilyevich makes us believe in a miracle, in love, and most importantly, that even the devil can be overcome if you know how to behave with him…

Ekaterina Evgenyevna Dmitrieva is a Doctor of Philology, Leading Researcher of the Department of Russian Classical Literature at the Gorky Institute of World Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

− It is known that Charles Dickens brought the image of Christmas to world literature. It is believed that Gogol was such a person in our Russian literature. How true is this?

− Not quite true. In fact, Gogol’s The Night Before Christmas began to be considered a Christmas story only in the 1880s. Until that time, the work did not have such a reputation. Let’s remember that The Night Before Christmas is a story included in the cycle of Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, in which there are other stories of the calendar cycle.

So, if we take, say, St. John’s Eve, then its events take place on the eve of a pagan holiday celebrated by Eastern Slavs on the summer solstice (June 24 / July 7) and coinciding with the Christian holiday of the Nativity of Saint John the Baptist. And this duality is actually very felt in Gogol’s story. And in another story of the same cycle – May Night, or the Drowned Maiden – the action takes place in the so-called Mermaid Week. In general, early Gogol has many stories and novellas timed to calendar holidays. The wonderful Gogol scholar Arkady Khaimovich Goldenberg has a whole book dedicated to calendar cycles in Gogol’s prose.

If we talk about the actual Christmas story, Gogol was far from the first in Russia to turn to this genre. It’s just that Gogol described this holiday so vividly and colorfully that one would like to say that he was the first. But, as it often happens, there is nothing “first” in the world, there will always be some predecessors. Medieval mysteries come to mind – a kind of pan-European trace of Gogol: the mysteries were always timed to certain church holidays. On the other hand, in the Slavic tradition, especially strong in Little Russia, there is the phenomenon of the nativity theater, one of the favorite plots of which is Christmas.

Let me remind you that the nativity scene was a large “box,” inside of which there was a stage, usually two-tiered. Scenes of the worship of the newborn baby Jesus were played out on the upper tier, and episodes based on the story of King Herod were played out in the lower tier. Herod, having learned from the magi that they were going to Bethlehem to worship the newborn “King of the Jews,” was afraid of the conspiracy and ordered to kill the baby. However, the magi did not reveal to him the whereabouts of the child, after which Herod ordered to kill all the children of Bethlehem under the age of two, hoping that the mysterious “future king” would be among them.

Nativity scene

In other words, the upper tier of the nativity scene was dedicated to a metaphysical action, symbolizing what is happening in heaven. Whereas in the lower tier, everyday stories were told. But there was no rigid border between the tiers. This, by the way, explains a lot in the poetics of Gogol himself. It was possible to move from the upper tier to the lower one, and vice versa. Therefore, the nativity drama is a genre precedent, which Gogol definitely focused on.

The first part of Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka was published in 1831. And the second book, which opened with The Night Before Christmas, was published in 1832. But by that time the public was already familiar with the wonderful story The Tale of Frol Skobeev, vaguely dated usually to the end of the 17th – beginning of the 18th century. Even if this story did not have the reputation of a Christmas story, however, according to the plot, Christmastide played a big role in it, since its main character, the rascal Frol Skobeev, wanting to marry the daughter of a carpenter, it was during the Christmastide period, at one of the evening parties, appeared disguised in female attire and successfully seduced his chosen one. In addition, already in the 1780s, The Tale of Frol Skobeev was remade into The Novgorod Girls’ Christmas Party, where the timing of the action to a certain calendar period was already indicated in the title.

Once upon a time, at the dawn of foggy youth, my friend and fellow graduate student Sergei Sapozhkov and I worked on a collection of short stories of the first half of the 19th century, called The Accidental Wedding. This collection opened with a later alteration of “Frol Skobeev” – The Novgorod Girls’ Christmas Party – from which, however, we were forced (the book was being prepared in the Children’s Literature publishing house) to remove all “immodest episodes.” Which I still regret. But this text is wonderful, and I highly recommend it.

In addition, even before the publication of Gogol’s The Night before Christmas in 1826 in the Moscow Telegraph magazine, his publisher Nikolai Alekseevich Polevoy published a cycle of Christmastide Stories. Of course, it is inappropriate to compare them with Gogol’s text in terms of the degree of artistry. But their worth is different. They contain significantly more ethnographic descriptions than Gogol’s. In addition, in the stories of Polevoy, everything is saturated with nostalgia about the past – evidence that even in the 1820s, the celebration of Christmas (Christmastide) felt like a sign of disappearing life. So, one of the narrators of the cycle recalls: “The wines are boiling, it’s getting dark, there will be games: old people sit down in circles and watch a handsome man or a pretty girl, blindfolded, catching her scattered enemies to the flapping of harnesses. Laughter! Merriment! Another one, running from corner to corner, runs from the catcher to another room. “He’s burned down!” everyone shouts, and the criminal takes the place of the blind man. Ah! How I also like other simple Christmas games of Siberians! Do you know how to grow a poppy?”

After all, this is “in its purest form” the very Christmastide or Christmas story, the plot of which does not exclude details of an ethnographic nature.

− And what caused the ethnographic aspect in Gogol’s work? Why was he so interested in, as he called them, Little Russians?

− Not only Gogol was interested in Little Russians, the current inhabitants of Ukraine (at that time this territory was called Little Russia). In fact, interest in Ukraine (Little Russia) among Russian writers dates to the second half of the 18th century. And there are many reasons for that.

First of all, the 1787 trip to the Crimea (the famous Tauride voyage) of Empress Catherine II, in which she was accompanied by many prominent persons, influenced her. For example, the aristocrat Prince Charles-Joseph de Ligne. The discovery of Little Russia, which the Empress makes on her way to Taurida, becomes essentially the discovery of some exotic space, which will receive various names in the future: Slavic Ausonia (Italy), noonday Russia, etc. The interest in this land was, of course, huge. At the beginning of the 19th century, sentimental descriptions of trips made to Little Russia appear, in which it is also described as a new pastoral Arcadia. For example, Journey to Little Russia by Pyotr Shalikov or Vladimir Izmailov’s Journey to Midday Russia. It is characteristic that in 1831, it was in a review of the first book of Evenings that the critic N.I. Nadezhdin introduced the concept of “Slavic Ausonia”: “Who does not know, at least by hearsay, that our Ukraine has a lot of curious, interesting, poetic in its physiognomy? Some secret agreement recognizes it as a Slavic Ausonia and anticipates a plentiful harvest for inspiration in it.”

On the other hand, interest in Little Russia and attention to it is connected with its heroic past, including the history of the Cossacks. So, Ryleev writes the Voynarovsky poem, the poetic play Bogdan Khmelnitsky. Pushkin will also turn to the Little Russian history in his Poltava poem.

If we talk about the ethnographic aspect in Gogol’s work, it should be noted that the 1830s are already the era of Romanticism in Russia. I use this designation with some trepidation because I always remember the saying of the witty Vyazemsky: “Romanticism is like a brownie, many believe it; there is a belief that it exists; but where to notice it, how to designate it, how to put a finger on it?” And yet, one can say that the unconditional sign of the new romantic art was an interest in a foreign culture. It is no coincidence that tourism in our modern understanding was born precisely in the romantic era (a tourist is someone interested in someone else – something that is unknown). So, in the era of Romanticism, interest in the East is growing, interest in exotic countries that need not be tamed, but to be understood precisely as foreign. And Little Russia was just the same exotic country that attracted attention with its unusual and unexplored nature.

That is why, as soon as Gogol is in Saint Petersburg, the first thing he writes to his mother and asks her to send as many different beliefs, descriptions of dresses, household plots as possible, and notes: “Everything Little Russian is fashionable here.” And this remark means that he is not alone in his interest in Little Russia. It’s just that Gogol realized the whiff of time very timely and realized what was relevant at that moment. But it was Gogol who amazingly managed to turn Little Russian folk stories into an artistic text of the highest level, very literary, although filled with elements of ethnography. Of course, we can say that The Night Before Christmas is a Christmas story. And yet not fully. You mentioned Dickens, who owns the definition of a Christmas story, one of the conditions of which is a good, happy ending. But if you think about it, does everything end well in the story The Night before Christmas by Gogol?

− Yes, I’d say.

− Let’s remember its ending. It would seem that everything ends well. Vakula got the shoes for his beloved and even managed to tame the devil. Oksana received the shoes but realized that she did not need them, but Vakula. In the ending they got married, a child was born. Everything is great. But let’s read the very last paragraph of the story: “When the late bishop, may he rest in peace, passed through Dikanka, he praised the beauty of its landscape and then stopped in front of a new house. A beautiful young woman holding a baby bowed to him from the porch. “Whose is this painting of a house?” the archbishop exclaimed. “Vakula the blacksmith’s,” replied Oksana, for it was she. “Fine work, very fine,” the bishop said approvingly, examining Vakula’s art. And there was plenty to examine: all the windows had scarlet borders, and on the doors Vakula had depicted Cossacks on horseback with pipes in their teeth. The bishop was even more impressed to learn that Vakula had fulfilled his vow and painted the entire left choir of the church with red flowers on a green background. But that wasn’t all. Beside the church door he had drawn a portrait of the devil in hell, so unspeakably ugly that everyone spat at it as they walked in. If a mother wanted to distract a fussy baby, she’d bring it closer to the painting, saying, “Here, look, what a yaka kaka,” and the fascinated child would hold back its tears, clutching at its mother’s breast.

What is Gogol doing here? A rather happy denouement of events is suddenly overlapped by a strange ending. Not everyone pays attention to this. The story ends with the mention of the devil, the child cries, the child is frightened. That is, after all, something terrible remains in this world. This means that it has not been overcome. And that’s Gogol for you.

− Gogol repeatedly emphasizes that the night before Christmas is a special time. The time when the devil can play pranks for the last time. Why did Gogol choose this time and describe it in this way?

− Here Gogol talks about frontier time. The frontier is the moment when something old ends and something new begins. In fact, Christmas is the end of the old year, the beginning of a new one, the end of the old world, the beginning of a new one.

A folklorist would explain to you that, according to beliefs, at Christmas, God, rejoicing at the birth of a baby, releases devils from hell. That is why evil spirits acquire special power exactly on the night before Christmas. Then the baby is born, and everything goes back to normal. It is believed that the greatest revelry of evil spirits falls precisely on the Christmastide period, it is at this time that she acquires special rights.

Such beliefs naturally attract people. People always want to believe in something that amazes them, shocks the imagination, something that does not fit into the usual ideas. And, of course, Gogol does not accidentally choose this time – a holiday in which pagan and Christian origins are combined. On the one hand, Christmas is a Christian holiday. But, for example, caroling, which is described in such detail by Gogol, was forbidden by the Stoglav Synod, and in general, the Church did not approve of this tradition, seeing in it (not without reason) the pagan basis.

Gogol himself in The Night Before Christmas makes a note that, apparently, Kolyada is a pagan god. However, in fact, Kolyada is just a Little Russian name for Christmas. This is due to the appearance in the 18th century of the so-called cabinet mythology, when nostalgia for domestic mythology arises and mythological characters are created, sometimes artificially, absent in the living tradition. At this time, the designations of some holidays begin to be used to designate the gods. This is a separate interesting story. So Kolyada is the very god who seems to have “hatched” from the word, turning into a deity who is glorified during caroling. I’m not sure if Gogol himself knew about such an artificial construction, but, in any case, this is what he builds his plot on.

− Meanwhile, there is a feeling that the evil spirits, in this case, represented in the form of a devil, are not very scary. Perhaps, against the background of Vakula, the devil does not cause fear. Why did Gogol show the evil spirits in this way?

− In fact, if you read folk tales, especially bailichkas, you will notice that evil spirits are often literally “tamed” by man. And, in general, they do not cause fear. In general, there can be two options in folklore tales. The first option is the devil or other evil spirits that do evil, which is almost impossible to cope with. And the second option is evil spirits, who can be overcome if you know how to behave with them.

And if we talk about Gogol, it is impossible not to mention the Baroque trace in his prose, that is, the influence of the Baroque style on the writer. The Baroque was generally characterized by the so-called figure of distribution, implying the polyvariance of the motif, the consideration of the same event (phenomenon) in different modalities and modifications. And on such variability Gogol bases everything. Take for example St. John’s Eve. The hero turns to the devil for help, to evil spirits. How does it end? Nothing good. The hero dies, and, in general, this is a very tragic story. In The Night Before Christmas, even though the end is not so rosy, Vakula still overcomes the devil and achieves everything he wanted.

And in this sense, Gogol has no single answer to the question: “Should you turn to the devil for help?” According to St. John’s Eve – no, by no means. According to The Night Before Christmas – why not?

− Interestingly, Gogol gives unusual abilities to other characters – Patsyuk and Solokha. Isn’t there some symbolism in this, as if the inhabitants of Dikanka are also some kind of unusual half-people?

− In fact, this is typical of the mentality of a rural resident. A person living in the countryside has a different attitude to nature, to the events taking place. They have much more feeling and faith in the presence of some invisible force. Therefore, Gogol very accurately reflects this mobility of the national consciousness.

What does Gogol really show? For example, Solokha, on the one hand, is Vakula’s mother. Quite a God-fearing woman who goes to church. On the other hand, she welcomes Cossacks. And also flies out through the chimney for a date with the devil.

By the way, I’ll tell you a little about how Gogol’s female characters seduce men. When the first volume of Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka was published, I decided to celebrate the appearance of the book by preparing all the dishes described in it, including those with which Solokha, and also Khivrya, treated and seduced the Cossacks. And I clearly understood what such seduction was worth. Because the dishes are insanely complex. In short, this is a lot of work.

Returning to how Gogol builds his narrative. For example, it is known that Solokha attracts Cossacks. Accordingly, among the residents of Dikanka, she enjoys the reputation of a witch (a kind of realized metaphor). This is what allows Gogol to turn her into a real witch, flying out through the chimney to further “play tricks” with the devil. Gogol uses a similar technique when creating other characters. It shows a certain mechanism for the birth of a legend. Someone didn’t like the woman, it seemed that she milked someone else’s cow, and then the cow’s milk went bad, or something else, and people start saying, “Oh, she’s a witch!” And Gogol, as if deliberately turns her into a real witch. Thus, the characters exist in two dimensions, which could be remotely compared to the two tiers of the nativity theater. One hypostasis of the image does not exclude the possibility of the existence of another.

− Let’s imagine the Christmas atmosphere according to Gogol. What is it like? What are its distinctive features? How does it possibly differ from other Christmas stories?

− Good question. Probably the simplest answer is that it is Gogol. He, as I have already said, is inherent in the duality of the narrative. It is appropriate to quote the beginning of the story here: “The day of Christmas eve ended, and the night began, cold and clear. The stars and the crescent moon shone brightly upon the Christian world, helping all the good folks welcome the birth of our Savior. The cold grew sharper, yet the night was so quiet that one could hear the snow squeak under a traveler’s boots from half a mile away. […] If Sorochintsy’s property assessor happened to be passing by on a troika of horses in his resplendent winter attire, he surely would have noticed the witch (here he describes how the witch flew out through the chimney), for that remarkable man noticed everything.”

Amazing description, isn’t it? And we already believe ourselves that the witch flew out, that the devil stole the moon, etc. And then Gogol suddenly gets distracted, allowing himself a certain assumption: if Sorochintsy’s assessor was passing by at that moment, he would surely have seen all this, because nothing escapes the Sorochinsy’s assessor. But this technique is very similar to what the German romantics called romantic irony: a demonstration of the maximum freedom of the author, who, like a demiurge, can create his own world and immediately, by some arbitrariness, destroy it.

And we understand that Gogol is being ironic. But literally after three lines, he goes back to describing the supernatural − and we again begin to believe in it. It is no coincidence that Gogol’s description of the flight of the witch Solokha and the devil is sometimes compared with the paintings of Bosch, who has a calm familiar world in the foreground, and some evil spirits fly somewhere in the background. That is, in Gogol, we are constantly faced with the transition from belief to unbelief. This, it seems to me, is what distinguishes his work.

− Is this work, with all its ambiguity, suitable for reading during the holiday week? Will readers be able to feel the Christmas atmosphere and pay attention to the features that you have described?

− Yes, of course, it is. No matter how strong these interruptions of Gogol’s irony, an amazing, colorful world appears before us, which, in general, remains in memory. Preparing for today’s conversation and rereading the story, I thought: “But some details that are important to Gogol, nevertheless completely slip from the reader’s memory.” For example, this interruption with the assessor, who could have seen the witch, is not remembered as vividly as, for example, the flight of Vakula riding the devil and the fabulous description of Saint Petersburg that follows. Gogol, of course, was able to create extravaganzas.

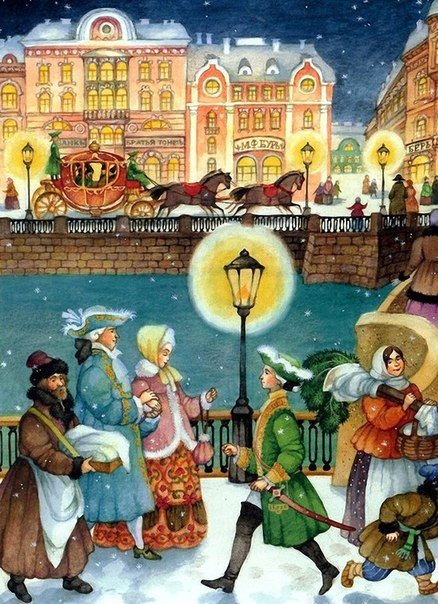

Illustration by Olga Ionaitis

Here is a quote from Innokenty Annensky, a wonderful poet of the late 19th - early 20th century: “Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka seem to us more like a romantic dream of youth than a finished creation of the artist. It’s still kind of maturing here. Nature itself is still kind of afraid to go out into the light of God in everyday attire.”

That is, everything described by Gogol is fabulous, beautiful, it fascinates, this is what we want to believe. But… with caution.

− Indeed, Gogol is ambiguous. For example, in Viy the writer scares us with his characters, and in The Night Before Christmas, he makes assumptions that evil spirits may not be so terrible.

− Gogol builds a narrative in line with popular beliefs. As the folklorists explained to me, if you know the rules, if you follow them, then you can overcome the devil. This is the popular consciousness. The main thing is to behave correctly.

Let’s not forget that Viy is already a later work of the writer. Therefore, it can be considered the next stage in the evolution of Gogol’s work. Moreover, while working on Viy, he wanted to destroy and burn all the “Evenings.” Gogol generally liked to burn his works, as we know. One day he destroyed almost the entire print run of Hanz Kuchelgarten − his first poem. And already from about 1834, he tried to destroy Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka. I mean, when he’s working on Viy, it’s a slightly different Gogol.

In general, Viy is perhaps the most mysterious story that does not cease to cause various attempts of interpretation. Much of it is unclear, the ends do not make ends meet. Especially when it comes to Viy himself. The prototype of this character was sought in different cultures, including in Eastern mythology. And recently I came across an article proving that this is a kind of Latin American image. But it is unlikely that Gogol knew Latin American characters.

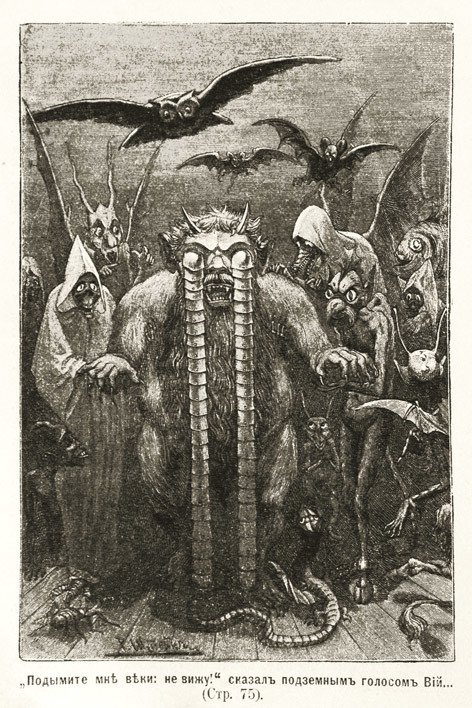

R. Stein. Viy. 1901. Outstanding Soviet scientists as V.I. Abaev, E.A. Grantovsky, and G.M. Bongard-Levin, in particular, were engaged in the study of this strange character of Ukrainian folklore. Analyzing Gogol’s Viy, they connected it with Scythian (Iranian) roots. Thus, V.I. Abaev concluded that the image of Viy goes back to the ancient East Slavic god Vey (Ukrainian: Viy), which corresponds to the Avestan god of death and wind Vayu in the pantheon of ancient Iranians (Scythians). The image of Viy may also correspond to Koshchei the Immortal

Gogol himself said that he was a character of Little Russian folklore. But he’s not there. Gogol liked to cover his tracks and confuse the reader.

I remember an anecdotal situation. As we remember, in the story A Terrible Vengeance, the text ends with a song by a bandurist singing about Khoma and Erema and Stklyar Stokoza. If everything is more or less clear with the folklore characters Khoma and Erema, then the mention of Stklyar Stokoza when we were preparing the first volume of academic Gogol caused confusion. It is clear that Stklar is a glazier. But who is Stokoza? I looked through all the previous editions of “Evenings” and comments on them. In some of them, it was said that Stokoza is a character of Ukrainian folklore. Folklorists, including Ukrainian ones, have not confirmed this. Rather, they were inclined to believe that there is no such character and that Gogol himself invented it. And do you know who he turned out to be? This did not occur to anyone, not even to our wonderful leader Yuri Vladimirovich Mann. I accidentally found out about it when I got to Nizhyn and once again asked: “Do you know who Stokoza is?” I think the museum cleaner told me, “Baby, this is Gogol’s uncle.”

That is, what did Gogol do? He took the name of his uncle Semyon Stokoza (a name that, by the way, everyone knows well) and introduced him into an artistic context that makes it seem that this is really a folklore character. And no one remembered the name of Gogol’s uncle.

The situation with Viy is similar. One of the possible explanations for the appearance of this terrible figure in Gogol is connected with the fascination in the mid-1830s with the so-called frenetic literature, which penetrates Russia from Europe, mainly from France. And which is characterized by a special interest not just in the fantastic, but in the terrible and terrifying that is also present in fiction. It seems that Viy is the embodiment of everything terrible, horrid, the very embodiment of evil, which came along with the literary fashion for this evil.

But it is also important to note that in the plot of Viy there is also the theme of vision. Extremely important already for Gogol. It is the vision that is one of the keys to the mystery of the death of Khoma Brut. It seems that Gogol’s hero was destined to see something beyond – something that a person cannot see. And this is, perhaps, a more serious statement question than what happened in Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka.

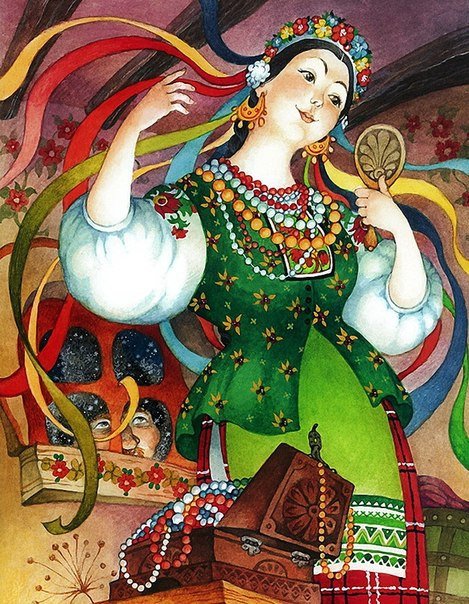

Illustration by Olga Ionaitis

− Let’s go back to The Night Before Christmas. Who is your favorite character from this story?

− Probably Oksana.

− Why?

− Because there is something very tender about her. After all, Gogol was accused of not being able to portray female characters, that either malicious and unpleasant old women or primitive, doll-like young maidens appeared in his works. And Oksana, it seems to me, is the most lively of all. Andrei Bely has a saying about Oksana that there is some kind of mockery in her, “trampling on cherished shrines.” And that Gogol’s Oksana is almost a Blok character: it is she who seems to anticipate Blok’s poems from the Beautiful Lady period, and the poems about the Beautiful Lady themselves.

But I also like Vakula.

− Why?

− He is a living character.

− From the people?

− It’s not that he’s from the people. It’s that he is ready to ride the devil for the sake of his beloved. And not everyone is capable of this.