Every millimeter of Earth is inhabited by millions of microbes. They are also present in space, and orbital stations have become their second home. We will tell you who happens to stay at the ISS in addition to the crew, and who lives there all the time.

Microorganisms cleverly adapt to the living conditions that humans modify so often. They have colonized everything around us on Earth and reached orbital stations where they survive and thrive in microworld of theirs.

At one time NASA expressed fear about the possibility of bringing “earthly” bacteria into space and vice versa. To avoid this, they have created a Planetary Protection Office. But space conditions let everything be kept under control (or so it seems). After some time NASA created devices to decontaminate all food products and materials before sending them to ISS. There seems to be no doubt that no microbe will break through safeguards so serious but things turned out to be not that way.

Research on microbial residents of the ISS has been carried out and continues to this day. Sure, bacteria from the natural environment are virtually absent at the ISS. Even though there are no forest, field or food-dwelling microbes, there is something else, albeit in small numbers. Most of them belong to one category – species inhabiting astronaut organisms. This conclusion was made by scientists during their first research at the ISS.

It turns out that if a residential house is completely isolated from external species, the microbial diversity will be the same. Here they are:

- Species related to Escherichia coli and Enterobacter;

- Bacillus subtilis microbes;

- Bacteries of the Corynebacterium genus.

However, new research has proven the presence of somebody else…

Conventionally such microorganisms can be divided into two groups: the former are transmitted from person to person, and the latter are extremophiles (living creatures capable of living and breeding in extreme conditions). Their study is important for successful space missions, so research continues to this day.

In 2015, NASA found dangerous bacteria and fungi at the ISS. They collected samples for studies from the air filter of the dust collector that had worked for 40 months without replacement and from the bag of the vacuum cleaner – these were surface-dwelling microorganisms from the ISS. As a result, it turned out that most of the bacteria from the ISS are related to human skin – a type of actinobacteria. They include the genera Corynebacterium and Propionibacterium (diphtheria and acne agents).

In 2021, geneticists from the University of Southern California (USA) and Hyderabad University (India) discovered microbes unknown to science at the International Space Station (ISS). Their study was published in the Frontiers in Microbiology journal.

Four strains of bacteria were “hiding” in the top panel of the research station, in the dome, on the surface of the dinner table and in the old HEPA filter (it was sent down to Earth in 2011). Only one of the strains (from the HEPA filter) was identified as Methylorubrum rhodesianum. The other three were sequenced and assigned to a new species of bacteria under the names: IF7SW-B2T, IIF1SW-B5, and IIF4SW-B5.

According to scientists, microorganisms appeared by no accident and it is not surprising – there are vegetable crops growing at the ISS, for example, tomatoes and salad.

A question predictably arises: how all microorganisms at the ISS can be counted? Here’s a brief checklist:

Stage 1. Collect samples.

We’ll need special cotton wads to swab the internal walls of the station at specific points. Then all wads are collected, packed and sent to Earth.

(!) It is important to remember two points:

- collection of samples should begin earlier than 36 hours before the ship departs.

- bacteries should not be allowed to multiply, so wads must be immersed in a special fluid. It does not kill microorganisms but suppresses their division.

Stage 2. Moving to the lab on Earth.

Bacteria, archaea, and fungi obtained from wads will be first cultured and then analyzed.

To separate one colony-forming organism from another, washes from wads are segregated to guarantee their isolation from each other.

Culturing is complete.

Now we can count and catalog our single-cell organisms.

(!) Particular attention should be paid to pathogenic bacteria and fungi.

This method is time-proven but not fully accurate: some microorganisms fail culturing under laboratory conditions but may nevertheless pose a threat to astronauts and station equipment.

This problem was solved by scientists from the United States in 2019 who proposed to use another method – the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) – simultaneously.

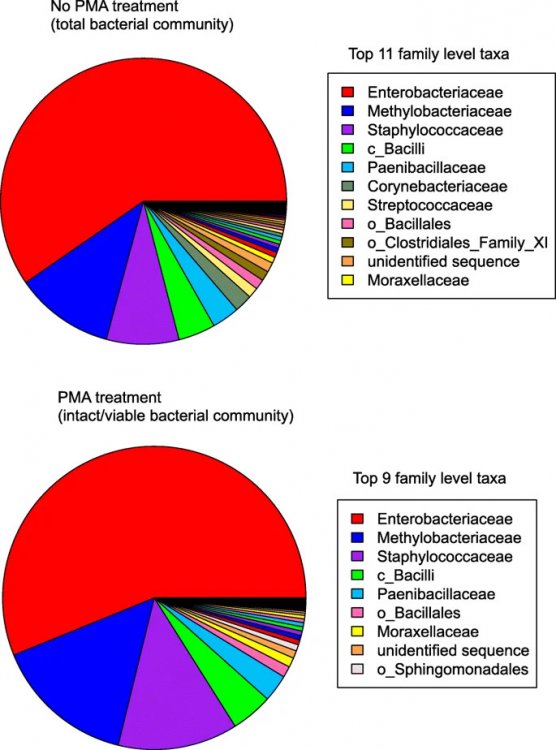

It allows the number of DNA molecules in the sample to be counted. And it helped make a more complete catalog of microorganisms living at the ISS.

In addition, experts came to another conclusion. It turned out that only 46 percent of all microbes from the surface of the American ISS segment and 40 percent of fungi can be detected and counted through the method of growing by culturing. The rest were non-culturable species.

Taxonomic diversity of ISS’s microbiome identified using PCR Aleksandra Checinska Sielaff et al. / Microbiome

Photo on the homepage: virtosmedia / Photo bank 123RF

Photo on the page: tawatchai07 / Photo bank Freepik