The Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge is known as “the Nobel Prize factory.” The Physics Department of the famous English university produced 29 scientists who were awarded the most prestigious prize for their work in science. Lord Rayleigh who discovered argon, Joseph John Thomson the physicist, and Lord Rutherford known as the “father of nuclear physics”.

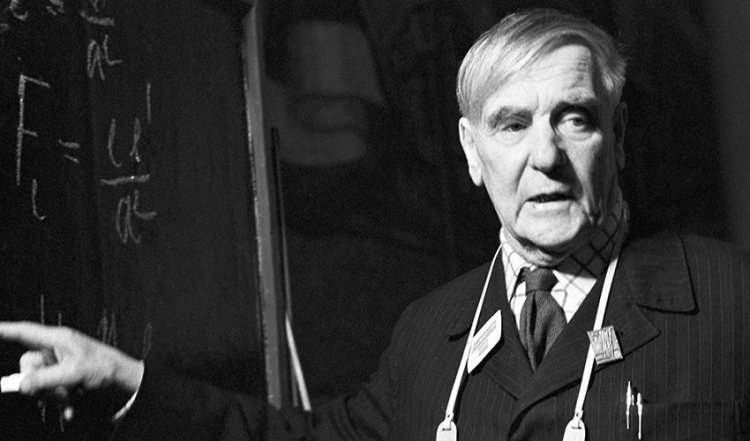

The Soviet scientist Pyotr Kapitsa is also on this list of honor. Pyotr Kapitsa was first educated at the Saint Petersburg Polytechnic Institute he entered in 1912. But his studies were interrupted two years later: Pyotr Kapitsa went to World War I as a driver in a medical team. After demobilization, he continued his studies in 1916: “the father of Soviet physics” Abram Ioffe got the promising student to work at the physics laboratory he led. After graduation, Pyotr Kapitsa stayed at the polytechnical institute as a teacher. Abram Ioffe, his supervisor, insisted on Kapitsa’s going abroad to expand his knowledge: the government denied their consent till Maxim Gorky intervened. Kapitsa went to Britain as a member of a special commission, where, thanks to Ioffe’s recommendations, he was hired to work at the Cavendish Laboratory under the direction of Ernest Rutherford.

As a scientist, Kapitsa became known for his works on ultra-strong magnetic fields. In 1922, the 28-year-old Kapitsa defended his Doctoral thesis on: “Movement of alpha-particles through matter and methods to produce magnetic fields.” Three and a half years later, in January 1925, Kapitsa was appointed Assistant Director of the Cavendish Laboratory for magnetic research, and after another 4 years – in 1929 – the scientist was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of London. A special laboratory costing £15,000 was built for.

The Cavendish Laboratory started getting sophisticated plants and improved equipment. The work to create equipment measuring temperature effects associated with the impact of strong magnetic fields on properties of a substance, led Kapitsa to study low temperature physics. Large amounts of liquefied gases were needed to produce such temperatures. In this area, Kapitsa created a plant to liquefy helium, which boils or liquefies at about 4.3 degrees Kelvin.

In the autumn of 1934, Pyotr Kapitsa visited the Soviet Union again: he would come to the USSR on a regular basis to see his family. The Government of the USSR invited the scientist to stay in his homeland multiple times but he kept declining. In 1934, he just was not allowed to leave the country; he tried asking Einstein and Rutherford for help but it did not work.

In 1935, Kapitsa was offered the position of the Director of the newly founded Physics Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Rutherford allowed the Soviet authorities to buy equipment from Kapitsa’s laboratory and send it to the USSR by sea.

Pyotr Kapitsa could not leave the Soviet Union for over 30 years – until 1965, when he was allowed to go to Denmark to receive the Niels Bohr International Gold Medal.

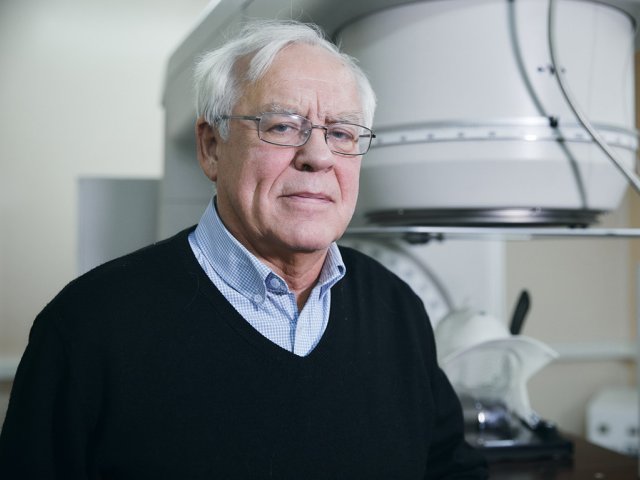

Photo: @ Oleg Kuzmin/TASS Photo Chronicle

Sources: library.istu.edu, stimul.online