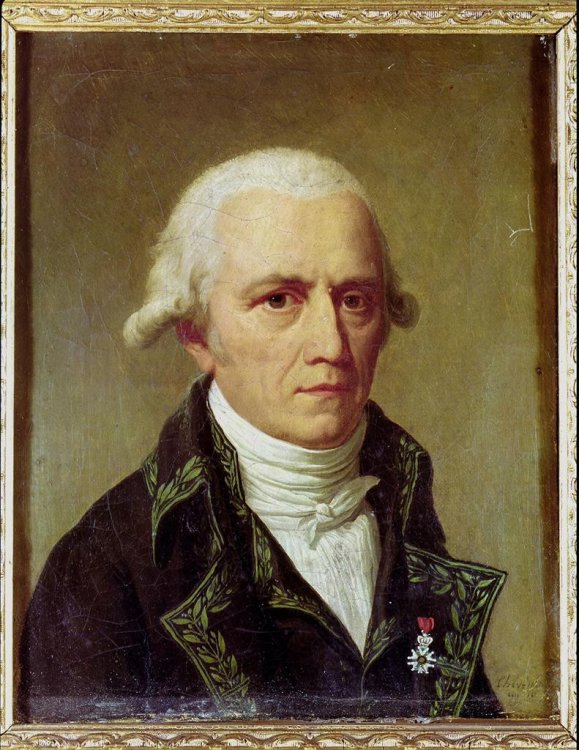

Official:

Jean Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet Lamarck. August 1, 1744 – December 18, 1829. French natural scientist.

Life and Work:

1. The inscription on the Lamarck monument in Paris reads, “To the founder of evolutionary though.” “Posterity will admire you. Posterity will avenge you, father,” says another inscription on the same monument. It is inscribed under a bas-relief depicting the blind Lamarck with his daughter, who recorded his thoughts. Writing the inscription for the monument, Cornelia guessed correctly – Lamarck is now considered the forerunner of Darwin.

2. French scientist Jean Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet Lamarck was born on August 1, 1744 in an impoverished but noble family in the small town of Bazentin in northern France.

3. His parents insisted that he pursue the spiritual path, but the young Lamarck did not stay long at the Jesuit college in Amiens. After his father’s death, he bought a horse and volunteered for the army during the Seven Years’ War.

4. He was fiercely brave in battle, but fortunately survived and even rose to the rank of officer. But a stupid joke of a friend at a halt led to a serious injury. Lamarck underwent a major surgery and spent almost a year recovering in Paris. It was then that he got interested in natural sciences and began to study medicine.

5. In his spare time, Lamarck studied botany. He was so successful that with Buffon’s help he published a three-volume work titled French Flora – a plant field guide, very simple and very convenient to use.

6. The Great French Revolution turned Lamarck from a botanist to a zoologist. The Royal Garden, where he worked as an herbarium curator, was converted into the Natural History Museum, but its botany department had been already occupied. Lamarck became a professor at the Department of Natural History of Insects and Worms.

7. He became interested in invertebrates; by the way, it was he who coined the term “invertebrates.” During that time, he created his famous ladder: he divided all living things into two groups – vertebrates and invertebrates, subdividing the latter into ten classes.

8. Lamarck distributed these classes in order of increasing their inherent “striving for perfection,” corresponding to their level of organization. Every living organism is on one of the steps of the ladder of beings. Osip Mandelstam wrote about this very ladder in his verse:

If living things are tiny ink blot marks

Frail evidence of a short, heirless day,

Then on this mobile ladder of Lamarck’s

The final rung I’ll gladly take.

9. Lamarck’s work reached its prime in Zoological Philosophy published in 1809. In it, the great Frenchman made the first attempt to create a holistic theory of the animal world evolution. Fearing to upset the church fathers, he outlined three stages of anthropogenesis, that is, the historical development of man from the ape-like form – vertical walking, reduction of the jaws, emergence of ideas and speech – and concluded it with the cautious phrase: “This is what the origin of man might look like if it were not different.”

10. Despite all the precautions, the contemporaries were not enthusiastic. Scientists ridiculed the new theory, while Napoleon, to whom Lamarck presented his fundamental work, subjected it to pejorative criticism. Everyone will recall the evolution theory precisely half a century later when Charles Darwin’s work is published.

11. The law of exercise and non-exercise of the organs became widely known. Lamarck used giraffes as an example: they must constantly stretch their necks to reach the leaves growing above their heads. Therefore, their necks become longer. In order to catch ants in the depths of an anthill, the anteater has to constantly stick out its tongue, so it becomes long and thin. On the other hand, the mole’s eyes are useless underground, and they gradually disappear. If the organ is often exercised, it develops. If the organ is not exercised, it gradually disappears.

12. Another Lamarck’s law is the law of inheritance of acquired traits. According to Lamarck, useful traits acquired by an animal are inherited by its offspring. Giraffes passed on their elongated necks, anteaters inherited their long tongues, and so on. This theory was heavily compromised by the notorious Lysenko. But the scientific debates around it have not subsided to this day.

13. Lamarck is revered as the creator of biological terminology and the word “biology” itself. In fairness, this term was introduced by the German scientist Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus independently of Lamarck.

14. During Lamarck’s lifetime, the German botanist Conrad Moench named a genus of Mediterranean cereals Lamarckia after him. Now, Lamarck’s name can be found in the names of many animals and plants, for example, a jellyfish species or a honey bee subspecies.

15. Apart from botany and zoology, Lamarck also authored works in other branches of science: hydrology, geology and meteorology. In Hydrogeologie, which he published in 1802, Lamarck put forward the principle of actualism in relation to interpreting geological phenomena. To make it clear to non-specialists: this is the assumption that in the past, the laws of nature were the same as now.

16. By the end of his life, Lamarck became completely blind – as they say, because of prolonged work with a magnifying glass and a microscope.