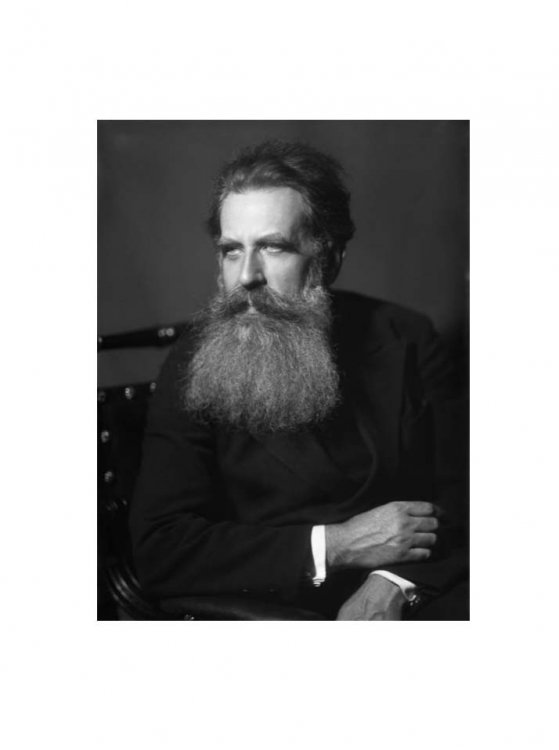

Official:

Otto Yulievich Schmidt. September 18 (30), 1891 – September 7, 1956. A Soviet mathematician, geographer, geophysicist, astronomer, explorer of the Arctic. Academician of the USSR Academy of Sciences. Hero of the Soviet Union.

Life and Work:

1.

Through this blizzard storm

Watch and admire

A baby was born

In the ice and fire

And next to it

Is the son of victory

He’s the second Schmidt

In Russia’s history...

This is how the rescue mission of SS Chelyuskin was represented by Marina Tsvetaeva in a poetic form. Otto Schmidt (the second Schmidt in Russia’s history after Lieutenant Pyotr Schmidt) was a scientist and explorer of the Arctic.

2. Otto Schmidt was born in Mogilev a quarter of a century later than Pyotr Schmidt, in 1891.

3. Just like the first Schmidt, Otto was of German origin: the ancestors of his father came from colonists who moved to Livonia in the second half of the 18th century.

4. Schmidt’s mother was a Latvian; his Latvian grandfather Fricis Ergle paid for the education of his gifted grandson in the gymnasium.

5. Otto’s father, a petty official, was not successful in his career and the family moved from place to place in search of a better life. So Otto as enrolled in the gymnasium in Mogilev, continued his studies in Odessa, and graduated in Kiev.

6. After graduation from the Kiev gymnasium with honors, Otto was admitted to the Physics and Mathematics department of Kiev University.

7. Schmidt remained in Kiev until 1917, the most revolutionary year, first as a student, then as a private lecturer and a quite-known scientist in the mathematician community: Schmidt’s Abstract Group Theory monograph is recognized as a serious contribution to higher algebra.

8. The revolution changed the country and the life of Otto Schmidt, too. He joined the Bolshevik Party and began to work hard ensuring the supply and cooperative issues.

9. Otto Schmidt was a commissioner of the People’s Commissariat for Food and the People’s Commissariat for Education: he developed projects for secondary, higher education and vocational training.

10. Being a member of a dozen committees and commissions, he managed to deliver lectures, reports and at the same time to run the State Publishing House Gosizdat. It was Otto Schmidt who proposed to publish the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, ensured the respective government decision, and began the publishing process in 1924.

11. In the summer of 1928, when the Basmachi movement was still undertaking uprising against the Soviets in the foothills of the Pamirs, the Academy of Sciences of the RSFSR organized an international expedition to the Pamirs in order to erase the “blank spots” from its map. The restless professor Schmidt joined the expedition, and became its actual leader two weeks later. It was this expedition that discovered and measured the highest peak of the Pamirs, which was later called Stalin’s Peak, and – in post-Soviet times – called Ismail Samani’s Peak.

12. Schmidt managed to do all his many things without breaking away from mathematics. In 1929, he founded the Department of Higher Algebra at Moscow State University and headed it for two decades.

13. That would be absolutely enough for anyone, but not the Red academician: the Arctic was his new passion. In 1930, together with Vladimir Wiese, he went on a scientific expedition on the Georgy Sedov icebreaking steamer. The two explorers discovered the island predicted by Wiese, and another island, which would later be called the Schmidt Island.

14. In the same 1930, Schmidt was appointed head of the All-Union Arctic Institute, and in 1932, he became head of Glavsevmorput, the Northern Sea Route administration.

15. Two years later, Schmidt sailed to the Arctic on the Alexander Sibiryakov steam icebreaker; the icebreaker passed the Northern Sea Route in one navigation for the first time in the world.

16. Then Otto Schmidt wanted to repeat the achievement on a regular steamer and the voyage of the SS Chelyuskin made Schmidt famous.

17. SS Chelyuskin was crushed by icepacks in the Chukchi Sea on February 13, 1934. Led by Schmidt, the Chelyuskinites managed to escape onto the ice floe. Keeping up the spirit of the expedition members, the leader also enlightened them at the same time. The topics of his lectures were as diverse as if they were delivered by a dozen of scientists: “On Scandinavian mythology,” “On music and composers,” “On the knowledge of the truth,” “On the future socialist society” and so on.

18. We do not know what exactly Schmidt said about the future socialist society, but he put up with the contemporary society. And helped others. “This German saved many good people from Cheka [Soviet secret-police]. In the year of the Great Terror, his beard was the only secure shelter where people could hide and be sure no police van would come to take them to the prison,” his contemporaries used to say about Otto Schmidt. Indeed, what kind of a police van can ever make to the Arctic?

19. In 1937, Schmidt initiated the establishment of the Institute of Theoretical Geophysics of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. He headed it and remained its director until 1949.

20. Astronomers know the “Schmidt hypothesis,” a cosmogonic hypothesis with the assumption that the planets were formed by combining cold solids of various sizes.

21. An icebreaker under construction was named after Otto Schmidt in 1935, during his lifetime. But SS Otto Schmidt never made any voyage. When Schmidt was dismissed as head of Glavsevmorput, the icebreaker was renamed as Anastas Mikoyan. However, another icebreaker, Otto Schmidt, managed to break some ice, but it was much later, in 1979-1991.

22. Of the three sons of Otto Schmidt, the most famous is Sigurd Ottovich Schmidt, Doctor of Historical Sciences, Academician of the Russian Academy of Education, author of 500 scientific papers.

23. The name of Otto Schmidt is immortalized in the names of the island, cape and town in Chukotka. Streets in different cities and the Russian Institute of Physics of the Earth are named after the remarkable scientist.

24. The history of Soviet onomastics includes rare names designed in the memory of this prominent figure in science such as Oyushminald and Lagshmivar. They stand for “Otto Yulievich Schmidt on the Ice Floe” and “Schmidt’s Camp in the Arctic.”