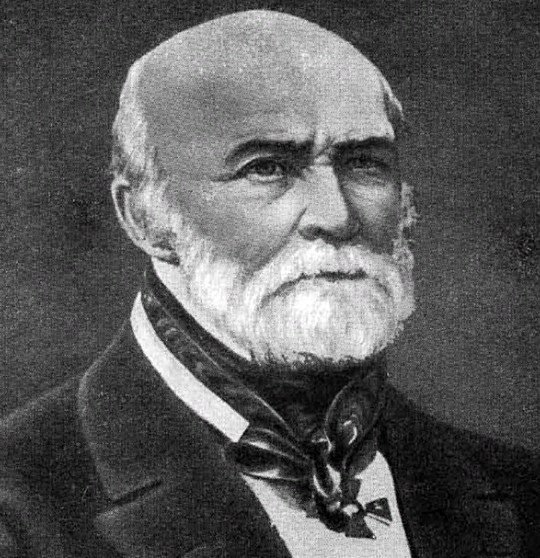

Official:

Nikolay Ivanovich Pirogov. November 13 (25), 1810 – November 23 (December 5), 1881. Russian surgeon and anatomist, natural scientist and teacher.

Life and Work:

1. Nikolay Pirogov participated in the Sevastopol defense during the Crimean War, as well as in the Franco-Prussian and Russo-Turkish wars. And in 1847, in the Caucasus, Pirogov led the first military operation of its kind: an operation under anesthesia on the battlefield.

2. Pirogov turned surgery into a science, created the first topographic anatomy atlas, invented the plaster cast for fractures, founded the Russian school of anesthesia, and made an invaluable contribution into public education.

3. The future professor and privy councilor was born in Moscow to a large family of the army treasurer, Major Ivan Ivanovich Pirogov. The thirteenth child, and the youngest of the six that survived, he was enthusiastic about medicine since childhood – ever since the “wizard” Dr. Mukhin visited their house. Professor Efrem Osipovich Mukhin healed his brother and thus predetermined Pirogov’s fate.

4. “The desire to imitate was born; having been inspired by Dr. Mukhin, I began to play the doctor; when I was 14 years old, Professor Mukhin advised my father to send me directly to the university; he patronized me during the exams, and at the end of the course he invited me to join the professorial institute,” Pirogov wrote in his memoirs later.

5. Having overstated his age by two years, Pirogov entered the university and at the age of 18 graduated from the department of medical sciences as a physician. The Professorial Institute mentioned in the memoirs was opened at the Imperial University of Dorpat to train future professors of Russian universities, and Pirogov became friends with Vladimir Dal there.

6. As a student, Nikolay Pirogov earned his bread in the autopsy room – this proved extremely useful for the surgery luminary later.

7. In 1833, the newly minted doctor of medicine went to the University of Berlin to improve his skills. He was already a well-known scientist when he arrived in Berlin: Pirogov’s dissertation was hastily translated into German.

8. Pirogov wanted to get a chair in Moscow, but he got it in Dorpat, and then in St. Petersburg, at the Medical and Surgical Academy. He operated often and well, developing new surgery techniques. But Pirogov could not save his first wife: she died of bleeding in childbirth. Nikolay Ivanovich was left with two small children.

9. They say that one day, passing through the market, Pirogov saw butchers sawing cow carcasses. The scientist paid attention to the fact that the cut showed the location of the internal organs clearly. He tried this method in the anatomical theater, sawing frozen corpses. Pirogov called this “ice anatomy” – it gave birth to a new medical discipline – topographic anatomy.

10. The first anatomical atlas, titled Topographical Anatomy Illustrated by Incisions Drawn Through the Frozen Human Body in Three Directions and published by the great surgeon, became an indispensable guide for his colleagues.

11. In 1847, Pirogov, a corresponding member of the Imperial St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, joined the active army in the Caucasus. There, he tested the surgical methods he had developed in the field, and for the first time, applied bandages soaked in starch, which proved to be more convenient and more reliable than the splints used before.

12. There, in the Caucasus, Pirogov was the first in the world to operate on the wounded under ether anesthesia in the field and performed about 10,000 such surgeries.

13. Nikolay Pirogov invented the plaster cast in the sculptor Nikolay Stepanov’s studio. “For the first time... I saw the effect of the plaster solution on canvas,” the scientist later recalled. “I guessed that it could be used in surgery, and immediately applied bandages and strips of canvas soaked in this solution to the compound fracture of the lower leg. The success was remarkable. The bandage dried in a few minutes: an oblique fracture with severe bleeding and skin perforation... healed without suppuration and any seizures. I was convinced that this bandage could find extensive use in military field practice.”

14. Pirogov used plaster bandages during the Crimean campaign widely. At the same time, he offered to use the sisters of mercy and trained the first nurses himself.

15. During the defense of Sevastopol in the Crimean War, he laid the foundations of military field surgery, offering a completely new method of caring for the wounded. The wounded were sorted at the first dressing station: the seriously wounded were operated immediately in the field, the lightly wounded were evacuated for treatment to stationary military hospitals.

16. During the Crimean War, Nikolay Nekrasov wrote about his namesake Pirogov as follows: “The war will pass, and his name will be spread all over Russia; it will reach where no Russian popularity has ever been before.” The reality was different, though.

17. Pirogov’s report to Alexander II about the backwardness of the Russian army and quartermasters’ theft did not convince the emperor. Pirogov was given a lifetime pension and sent to Odessa as a trustee of the Odessa School District.

18. Pirogov took the new assignment as a mission. In one of his letters, he wrote: “As a father and as a Russian, I understand the importance of education for our land and sincerely wish to see it based not on the temporary needs of the country alone, but on deeper and more correct principles.”

19. “He was a rare trustee – a thoughtful philosopher, who would carry out serious pedagogical reforms, which were thoroughly thought out in advance and were not a result of an accidental thought, but a consequence of an entire pedagogical system that he strictly followed,” a contemporary recalled. Among Pirogov’s reforms are the respectful attitude to students regardless of their age and the abolition of flogging.

20. Becoming the school district trustee, Pirogov became a real ruler of the young people’s thoughts. In this regard, they said that during the Crimean War, he would cut off hands and feet, and then put heads back.

21. From Odessa, Pirogov was transferred to the position of the Kiev School District trustee, and then dismissed for refusing to spy on students and inform on them.

22. In the early 60s, Pirogov supervised scientists studying abroad. There he saved the leg, and possibly the life of the wounded Giuseppe Garibaldi. This did not go unpunished: Nikolay Ivanovich was relieved of supervising the training of Russian young scientists.

23. Pirogov retired to his estate Vishnya near Vinnytsia, and left home only to give lectures at St. Petersburg University. Only two of his trips were prolonged: during the Franco-Prussian and Russo-Turkish wars.

24. During the Franco-Prussian War, the International Red Cross asked Pirogov to come to the battlefield. And during the Russo-Turkish war, the quite elderly scientist arranged field surgery, treated, and operated the wounded in Bulgaria for several months.

25. Bulgaria did not forget his good deeds. As a sign of gratitude to Pirogov, 26 obelisks, 3 rotundas, and a monument in Skobelev Park in Plevna were erected there. In the village of Bokhot, on the site where the Russian hospital stood, the N. I. Pirogov Museum Park was created.

26. The scientist conducted his very last experiment after his death: Pirogov was embalmed according to a recipe that he invented himself.

27. When doctors from all over Russia raised funds to erect a monument to Pirogov in Moscow, the Moscow authorities did not allow the construction. Sklifosovsky went to St. Petersburg, obtained an audience with Emperor Nicholas II, and got the required permission. That was how Russia’s first monument to the scientist was erected – it still stands on Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Street, on the Devichye Pole square.

28. Next to Pirogov Mausoleum in Vinnytsia is the Church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker – another monument to the wonderworker Nikolay Pirogov.